by Michael Roberts

The sixth report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

(IPCC) runs to nearly 4,000 pages. The IPCC has tried to summarise its

report as the ‘final opportunity’ to avoid climate catastrophe. Its

conclusions are not much changed since the previous publication in 2013,

only more decisive this time. The evidence is clear: we know the cause

of global warming (mankind); we know how far the planet has warmed (~1C

so far), we know how atmospheric CO2 concentrations have changed since

pre-industrial times (+30%) and we know that warming that has shown up

so far has been generated by historical pollution. You have to go back

several million years to even replicate what we have today. During the

Pilocene era (5.3-2.6 million years ago) the world had CO2 levels of

360-420ppm (vs. 415ppm now).

In its summary for Policy makers, the IPCC states clearly that climate change and global warming is “unequivocally caused by human activities.” But can climate change be laid at the door of the whole of humanity or instead on that part of humanity that owns, controls and decides what happens to our future? Sure, any society without the scientific knowledge would have exploited fossil fuels in order to generate energy for production, warmth and transport. But would any society have gone on expanding fossil fuel exploration and production without controls to protect the environment and failed to look for alternative sources of energy that did not damage the planet, once it became clear that carbon emissions were doing just that?

Indeed, we now know that scientists warned of the dangers decades ago. Nuclear physicist Edward Teller warned the oil industry all the way back in 1959 that its product will end up having a catastrophic impact on human civilization. The main fossil fuel companies like Exxon or BP knew what the consequences were, but chose to hide the evidence and do nothing – just like the tobacco companies over smoking. The scientific evidence on carbon emissions damaging the planet, as presented in the IPCC report, is about as inconvertible as smoking in damaging health. And yet little or nothing has been done, because the environment must not stand in the way of profitability.

The culprit is not ‘humanity’ but industrial capitalism and its addiction to fossil fuels. At a personal level, in the last 25 years, it is the richest one percent of the world’s population mainly based in the Global North who were responsible for more than twice as much carbon pollution as the 3.1 billion people who made up the poorest half of humanity. A recent study found that the richest 10 percent of households use almost half (45 percent) of all the energy linked to land transport and three quarters of all energy linked to aviation. Transportation accounts for around a quarter of global emissions today, while SUVs were the second biggest driver of global carbon emissions growth between 2010 and 2018. But even more to the point, just 100 companies have been the source of more than 70% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions since 1988, according to a new report. It’s big capital that is the polluter even more than the very rich.

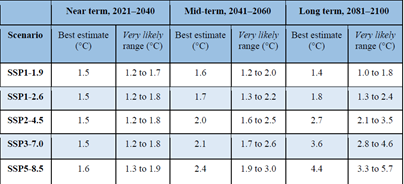

The IPCC material distils a massive pool of data into a report that it hopes is irrefutable and alarming enough to force more radical change. And it provides various scenarios on when global temperatures will reach the so-called Paris target of 1.5c degrees above average pre-industrial levels. Its main scenario is called the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP1-1.9) scenario in, in which it is argued that if net carbon emissions are reduced, then the 1.5C target will be reached by 2040 at the latest, then breach the target up to 2060 before falling back to 1.4C by the end of the century.

But this is the most optimistic of five scenarios on the pace and intensity of global warming in the 21st century and it’s bad enough! The other scenarios are way bleaker, culminating in SSP5-8.5 which would see global temperatures rise 4.4C by 2100 and continuing upward thereafter (Inset 1). There isn’t a scenario better than SSP1-1.9 and these are ignored by the IPCC.

Shared socioeconomic pathways

SSP1-1.9 is the most optimistic scenario, global CO2 emissions are cut to net zero by 2050. There is a huge shift to sustainable development, with well-being prioritised over pure economic growth. Investments in education and health rise and inequality falls. Extreme weather continues to increase in frequency, but the world avoids the worst impacts of climate change. Global warming is kept to around 1.5C, stabilising around 1.4C by the end of the century.

SSP1-2.6 is the next-best scenario, global CO2 emissions fall but net zero is not reached until after 2050. It assumes the same socioeconomic shifts as in SSP1-1.9 are met. But temperatures are left 1.8C higher by 2100.

SSP2-4.5 is the “middle of the road” scenario (i.e. the most likely). CO2 emissions hover around current levels before starting to fall mid-century, but do not reach net-zero until nearer 2100. Shifts towards a more sustainable economy and improvements in inequality follow historic trends. Temperatures rise 2.7C by the end of the century.

SSP3-7.0 is one where emissions and temperatures continue to rise steadily, ending at roughly double current levels by 2100. Countries become more competitive national and food security is prioritised. Average temperatures rise by 3.6C.

SSP5-8.5 is the apocalyptic scenario. CO2 emissions roughly double by 2050. The global economy continues to grow quickly by exploiting fossil fuels, lifestyles remain energy intensive and average global temperatures are 4.4C higher as we enter the 22nd century.

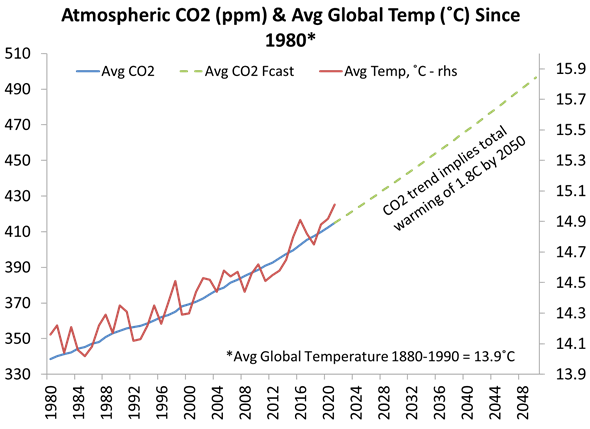

No probabilities are offered for any of these scenarios – just the hope and expectation that SSP1 will happen. But the pace of emissions growth and temperature is already on a much faster trajectory. The planet has already warmed 1.0-1.2C depending on how you want to measure it (current or 10-year average). The trend is well established and is tending to surprise on the upside, not the downside. Furthermore, the rate of change in atmospheric chemistry is unprecedented and continues to accelerate.

Even at 1.5oC, we will see sea level rises of between two and three metres. Instances of extreme heat will be around four times more likely. Heavy rainfall will be around 10 percent wetter and 1.5 times more likely to occur. Much of these changes are already irreversible, like the sea level rises, the melting of Arctic ice, and the warming and acidification of the oceans. Drastic reductions in emissions can stave off worse climate change, according to IPCC scientists, but will not return the world to the more moderate weather patterns of the past.

Even if we assume the SSP1-1.9 objectives can be met by 2050, cumulative global CO2 emissions would still be a third higher than the current 1.2trn tons of CO2 emitted since 1960. That would push atmospheric CO2 beyond 500ppm, or 66% higher than where things stood in the pre-industrial period. That pathway implies 1.8C of warming by 2050, not 1.5C.

The reality is that the IPCC’s very low emissions scenario is improbable: and the global temperature is likely to hit 1.5C much earlier than 2040 and reach a much higher level, even with the conditions of SSP1 in place, namely a 50% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2050.

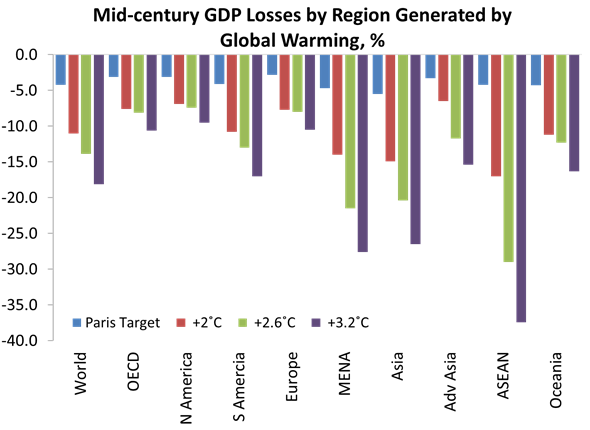

More likely, global warming will reach around 1.8C by 2050 and 2.5C by the end of the century. That means even more drought and flood events than currently forecast and so even more suffering and mounting economic losses from the mix – a loss in world GDP of 10-15% on current trajectories and double that in the poor Global South.

António Guterres, the secretary-general of the United Nations, responded to the report by taking aim at the fossil fuel industry: “This report must sound a death knell for coal and fossil fuels, before they destroy our planet.” But how? First and foremost, it’s not enough to end the government subsidies and financing of fossil fuel sectors by governments around the world (and that is still going on). Instead, there must be a global plan to phase out fossil fuel energy production.

Left Democrat Robert Reich, former official in the Clinton administration, reckons the answer is to stop oil company lobbying, oil exploration, ban oil exports and make the oil companies pay compensation. He stops short of public ownership. But how can a really successful plan to stop global warming work unless the fossil fuel companies are brought into public ownership? The energy industry needs to be integrated into a global plan to reduce emissions and expand superior renewable energy technology. This means building renewable energy capacity of 10x the current utility base. That is only possible through planned public investment that transfers the jobs in fossil fuel companies to green technology and environmental companies, where there will be many jobs.

Second, public investment is needed to develop the technologies of carbon extraction to reduce the existing stock of atmospheric emissions. The IPCC says that going beyond net zero by removing large quantities of carbon from the atmosphere “might be able to reduce warming”, but carbon removal technologies “are not yet ready” to work at the scale that would be required, and most “have undesired side effects”. In other words, private investment is failing to deliver on this so far.

Decarbonizing the world economy is technically and financially feasible. It would require committing approximately 2.5 percent of global GDP per year to investment spending in areas designed to improve energy efficiency standards across the board (buildings, automobiles, transportation systems, industrial production processes) and to massively expand the availability of clean energy sources for zero emissions to be realized by 2050. That cost is nothing compared to the loss of incomes, employment, lives and living conditions for millions ahead.

End fossil fuel production through public ownership and a global investment plan – this is just utopia, critics may say. But then, market solutions of carbon pricing and taxation, as advocated by the IMF and the EU, are not going to work, even if implemented globally – and that is not going to happen.

There is less than three months before the delayed COP26 conference in Glasgow. The previous two major conferences produced nothing at all: COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, and COP21 in 2015 (the Paris Agreement) only committed nations to voluntary emissions reductions targets that would lead to about 2.9oC of warming if achieved. Glasgow is shaping up to be no less of a failure.

No comments:

Post a Comment