The victory of Benoit Hamon as the new leader of the ruling Socialist party in France sets the scene for an unpredictable outcome from the upcoming presidential election in April-May.

Hamon is a Corbyn-Sanders type left leader who defeated the right-wing Blairite-Clinton candidate in the socialist primary that saw nearly 2m vote. He stands for cutting the working week, boosting the minimum wage and reversing various neo-liberal measures introduced by incumbent ‘socialist’ President Hollande, who is so unpopular (with 4% approval) that he decided to not to run again.

Hamon starts way behind in the public opinion polls, with about 15% of those voting likely to support him, but ahead of the ‘far left’ candidate Jean-Luc Melenchon with 10%. The leader of the pack is Marie Le Pen, head of the (formerly openly fascist) racist, anti-immigrant, anti-EU Front National (NF), who is polling about 25%. The centre-right, neo-liberal main capitalist party, the Republicans, have picked Francois Fillon, who wants to increase the working week, privatise more and cut public employees and services sharply. Fillon, who has been caught in a scandal of paying his wife €800,000 as his ‘secretary’ from public funds for doing nothing, is polling about 22%. Then there is the so-called centre candidate, a former right-wing ‘socialist’ minister, Emmanuel Macron, who is pro-EU, wants more neo-liberal policies etc. He is getting about 21%.

So it’s all wide open. As the French presidential election is over two rounds, with the top two in the first round then having a run-off, the most likely outcome is that Le Pen may get to the second round but then be roundly defeated by one of the others (in a second round any of the others are ahead against Le Pen by about 60-40). So it is unlikely that France will vote in a racist Eurosceptic president.

But that does not rule out a new right-wing president who will try to boost profitability at the expense of labour, by raising the working week, imposing stringent labour laws, cuts in public services, pensions and have more privatisations. That’s because French capital needs to act as it slips further behind its major partner in Europe, German capital.

The French economy picked up the last quarter of 2016, but it was a very modest recovery. The French economy grew 1.1 percent in all of 2016, compared with 3.2 percent in Spain and 1.9 percent in Germany. The unemployment rate remains stuck close to 10 percent compared to just 3.9% in Germany.

The reality is that French capital has been in trouble for some time. The best estimate of the profitability of French capital in the last 50 years shows that after the profitability slump of the 1960s that all the major capitalist economies experienced, French capital made only a limited recovery in the so-called neo-liberal era.

That was partly due to the failure of French industry to invest and compete in world markets and eventually in the Eurozone compared to Germany. And it was also partly due to the stubborn militancy of French labour to allow cuts in wages and conditions and to preserve public services and benefits – France has the best national health service in the world and still relatively good social benefits and pensions (although these have been eaten away). And it has an official 35-hour week which is enforced by the labour movement.

At the end of the 20th century, profitability peaked and began to fall again. It is now at a post-war low. As a result, French capital is struggling to compete. Indeed, since the euro started in 1999, the profitability of French capital has plummeted 27% compared to a 21% rise in Germany. Profitability is still down a staggering 22% since the peak just before the global financial crash in 2007 – that’s way more than the decline in Germany or the Euro area average.

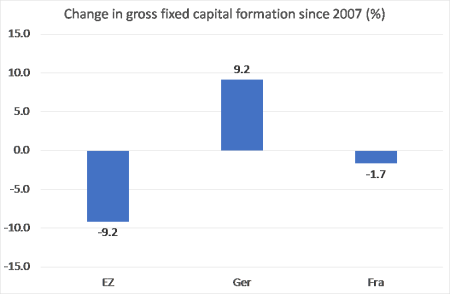

As a result, investment, particularly business investment, has stagnated in the ‘recovery’ since 2009.

As investment has been so poor, growth in productivity has been low (as in many other capitalist economies).

French productivity levels (GDP per hour worked) seem higher than the G7 and the UK. But this is partly an illusion because the unemployment rate is close to 10% or double that of the UK and Germany. When you account for that, French productivity is not much higher than the UK.

So this upcoming election is important. French capital wants a president elected who will introduce policies designed to reverse the long-term secular decline in the profitability of capital and put French labour in its place. For this, they look to Fillon or Macron – either will do. But votes do not always work out as the strategists want or expect – as we have seen in the UK with Brexit and Trump in the US.

It is still unlikely that Le Pen will enter the Elysee Palace or that Hamon or Melenchon will combine to enable a leftist candidate to get into the second round and defeat Le Pen. But it’s possible. But whatever the outcome, the next French president will face major challenges with an economy that has sluggish growth and investment, high unemployment and growing ethnic divisions. And that is not even considering the probability that there will be a new global slump during the next presidency.

No comments:

Post a Comment