World leaders are meeting in Japan at the so-called G7 meeting of top capitalist economies. The state of the global economy is the main subject. There will be no agreement on what to do about sluggish economic growth, still high unemployment in many countries, falling average real incomes in many others and above all, for capitalism, low productivity growth and dismal business investment.

The policy answers from the G7 leaders to this continued Long Depression vary from “structural reform” (i.e. neo-liberal measures to squeeze more surplus-value out of labour through reductions in labour rights; hiring and firing; privatisation) to more monetary easing (quantitative easing, negative interest rates) and then to fiscal stimulus (more government spending). But nobody is agreed on common action, so nothing will change on policy.

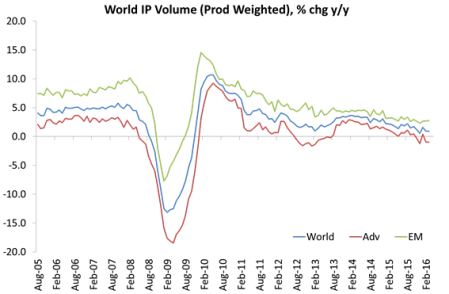

What is changing is the further deterioration of the world capitalist economy. Global industrial output growth continues to slow and in the case of the G7 economies (red line below), industrial production is now contracting.

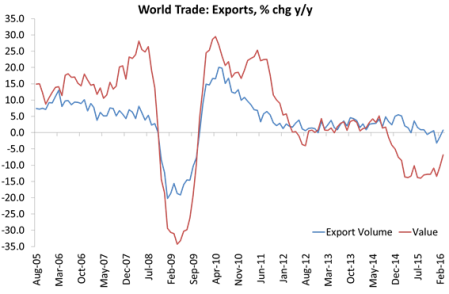

And world trade, something that I have reported on before, is in significant negative territory (red line below). This is partly due to the collapse in energy and other industrial raw material prices. But even when you strip out the impact of the deflation in prices, world trade volume is basically static (blue line) and well below even the low world GDP growth rate of around 2.5%. Countries with low domestic demand can expect no compensation through exports.

The most worrying thing for global capitalism is that the US economy, the best performer among the G7 since the end of the Great Recession in 2009, is also showing signs of fading. In previous posts, I have argued that it would not be China that would pull down the world into a new recession but what happened in the US, which remains the most important capitalist economy, both in production and finance.

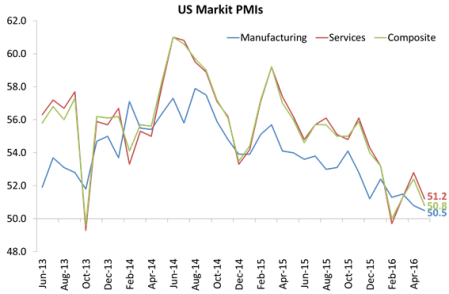

The latest survey of business activity among US companies, the so-called purchasing manager index (PMI), made dismal reading. The PMI surveys companies to see if they think they are increasing production or not. Anything over 50 suggests expansion. The latest May figure shows that the US economy, both industry and services, is barely growing, with the PMI at just 50.8 (green line) compared to over 60 just two years ago.

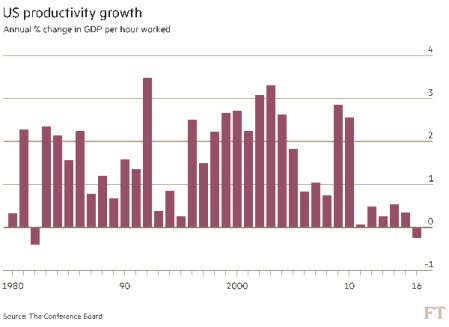

And the prospects for a pick-up in growth ahead are not good. The US Conference Board monitors the state of productivity around the world. That’s the measure of output per worker (and per hour). Productivity growth plus growth in the labour force constitutes the make-up of long-term real GDP growth. Population and employment growth has been slowing in the Long Depression, so productivity growth is even more important.

The latest data from the Conference Board are particularly shocking. Output per person grew just 1.2 per cent across the world in 2015, down from 1.9 per cent in 2014. Productivity growth in the eurozone, measured by gross domestic product per hour, is set to be a feeble 0.3 per cent and barely better in Japan at 0.4 per cent. But the US slowed last year to just 0.3 per cent from 0.5 per cent in 2014, well below the pace of 2.4 per cent in 1999 to 2006. Britain’s output per hour worked fell to an average annual increase of only 0.2 per cent between 2007 and 2013 and after a false dawn in 2015, is expected to show zero growth this year.

And now the Conference Board expects -0.2% for the US this year, the first contraction in three decades. “Last year it looked like we were entering into a productivity crisis: now we are right in it,” said Bart van Ark, the Conference Board’s chief economist. The Conference Board pleaded that “Companies really need to invest seriously in innovation. It is time for companies to move on the productivity agenda to turn this story around.”

But they are not. US business investment fell 0.4% in first quarter of 2016 compared to the first quarter of 2015 and spending on equipment fell for the first time since the Great Recession ended.

Why are companies in the G7 not rising to the occasion and investing more and more in new technology to get productivity growth up? The usual mainstream economics argument was repeated by Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein recently. The notorious head of the world’s most rapacious investment bank had one word to tie together everything happening on Wall Street and in the global economy right now. “It all comes down to confidence”, he said at the firm’s annual meeting. Right now, Blankfein said, “we’re in a low-confidence environment.” But Blankfein’s answer begs the question: why is there a ‘lack of confidence” among companies to raise investment? I have answered this question on numerous occasions in this blog. The latest is in this post. And see this by Jose Tapia Granados.

Corporate investment is stagnating or falling because profitability remains low and total profits have stopped rising. Also corporate debt burdens are beginning to weight down on ‘confidence’. Last year in the US, Last year business debt, excluding off balance sheet liabilities, rose $793 billion, while total gross private domestic investment (which includes fixed and inventory investment) rose only $93 billion.

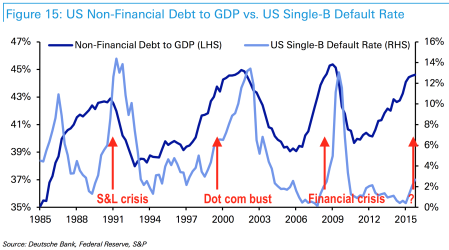

More than 70 corporate borrowers have defaulted globally so far this year, piling up at the fastest pace since 2009 and closing in on the 113 issuers that defaulted in 2015, according to Standard Poor’s. It’s true that most of these are in the hard-hit energy and mining sectors. the energy and resources sector accounted for more than half of the overall 72 issuers that have defaulted so far in 2016. Within this, 29 have been in the oil and gas industry, 12 were in metals, mining and steel and one was a utility company.

But the S&P is concerned that defaults could spread to other sectors: “So far, there has been little spillover effect into other sectors, but we are not ruling this out in the coming quarters. We also expect this stress on many U.S. oil and gas companies to persist with continued low oil prices, ongoing cash flow deficits as a result of declining prices, more limited debt-funding sources (including credit facilities and bank lending), and potentially limited benefits from plans to further cut capital expenditures.” Corporate defaults are heading back up to territory last seen in 2009, when the financial crisis hit bottom.

So while the G7 leaders ponder the state of the world, far from corporations taking up the challenge of boosting productivity through more investment and R&D, they are holding back. And a missing ‘confidence fairy’ is not the reason.

No comments:

Post a Comment