by Michael Roberts

Do ‘excessive’ wage rises lead to rising inflation and thus drive

economies into a wage-price spiral? Back in 1865, at the International

Working Men’s Association, Marx debated with IWMA Council member Thomas

Weston. Weston, a leader of the carpenter’s union, argued that asking

for increased wages was futile because all that would happen would be

that employers would put up their prices to maintain their profits and

so inflation would quickly eat into purchasing power; real wages would

stagnate and workers would be back to square one because of a wage-price

spiral.

Marx responded to Weston’s argument firmly. His reply, which was eventually published as a pamphlet, Value, Price and Profit, was basically as follows. First, “wage rises generally happen in the track of previous price rises” – it’s a catch-up response, not due to ‘excessive’ and unrealistic demands for higher wages by workers. Second, it is not wage rises that cause rising inflation. Many other things affect price changes, Marx argued: namely “the amount of production (growth rates – MR), the productive powers of labour (productivity growth – MR), the value of money (money supply growth – MR), fluctuations of market prices (price setting – MR), and different phases of the industrial cycle” (boom or slump – MR).

Moreover, “A general rise in the rate of wages will result in a fall of the general rate of profit, but not affect the prices of commodities.” In other words, wage rises are much more likely to lower the share of income going to profits and thus eventually lower the profitability of capital. And that is the reason capitalists and their economist prize-fighters oppose wage rises. The claim that there is a wage-price spiral and that wage rises cause price rises is an ideological smokescreen to protect profitability.

Was Marx right? Well, modern mainstream economics has continued to claim that ‘excessive’ wage rises will cause rising inflation and create a wage-price spital. Take these following views in the current inflation upsurge. First, there is the recent statement by Andrew Bailey, the Governor of the Bank of England. “I’m not saying nobody gets a pay rise, don’t get me wrong. But what I am saying is, we do need to see restraint in pay bargaining, otherwise it will get out of control”.

Or even more explicitly and following the argument of Thomas Weston over 150 years ago, Jason Furman, former economic adviser to US president Obama, put it this way. “When wages go up that leads prices to go up. If airline fuel or food ingredients go up in price, then airlines or restaurants raise their prices. Similarly, if wages for flight attendants or servers go up then they also raise prices. This follows from basic micro & common sense.”

Well, it may follow from “basic micro and commonsense” in mainstream economics. But it is just plain wrong. And this week, the IMF has compiled a comprehensive data analysis of the movement of wage and price rises that refutes Bailey and Furman. The IMF “address these questions by creating an empirical definition of a wage-price spiral and applying this on a cross-economy database of past episodes among advanced economies going back to the 1960s.” So over 60 years and in many countries.

What did the IMF find: “Wage-price spirals, at least defined as a sustained acceleration of prices and wages, are hard to find in the recent historical record. Of the 79 episodes identified with accelerating prices and wages going back to the 1960s, only a minority of them saw further acceleration after eight quarters. Moreover, sustained wage-price acceleration is even harder to find when looking at episodes similar to today, where real wages have significantly fallen. In those cases, nominal wages tended to catch-up to inflation to partially recover real wage losses, and growth rates tended to stabilize at a higher level than before the initial acceleration happened. Wage growth rates were eventually consistent with inflation and labor market tightness observed. This mechanism did not appear to lead to persistent acceleration dynamics that can be characterized as a wage-price spiral.”

And there’s more: “We define a wage-price spiral as an episode where at least three out of four consecutive quarters saw accelerating consumer prices and rising nominal wages.” And the IMF finds that “Perhaps surprisingly, only a small minority of such episodes were followed by sustained acceleration in wages and prices. Instead, inflation and nominal wage growth tended to stabilize, leaving real wage growth broadly unchanged. A decomposition of wage dynamics using a wage Phillips curve suggests that nominal wage growth normally stabilizes at levels that are consistent with observed inflation and labor market tightness. When focusing on episodes that mimic the recent pattern of falling real wages and tightening labor markets, declining inflation and nominal wage growth increases tended to follow – thus allowing real wages to catch up.“

What does the IMF conclude? “We conclude that an acceleration of nominal wages should not necessarily be seen as a sign that a wage-price spiral is taking hold.” In inflationary episodes, wages just try to catch up with prices. But even then, wage rises do not cause wage price spirals – thus Marx’s view is confirmed.

And if you want immediate proof of this, take this week’s wage settlement between German manufacturing employers and IG Metall union, Germany’s biggest. Workers will get pay rises well below Germany’s inflation rate, currently at a 70-year high of 11.6 per cent, receiving 5.2 per cent next year and 3.3 per cent in 2024, plus two €1,500 lump sum payments. Jörg Krämer, chief economist at Commerzbank, said unions and employers had “found a compromise on how to deal with the income losses caused by the sharp rise in the costs of energy imports”. He added: “I would not yet call this a wage-price spiral.” Indeed not, as even the best organized workers in Germany will have to accept reductions in their purchasing power over the next two years.

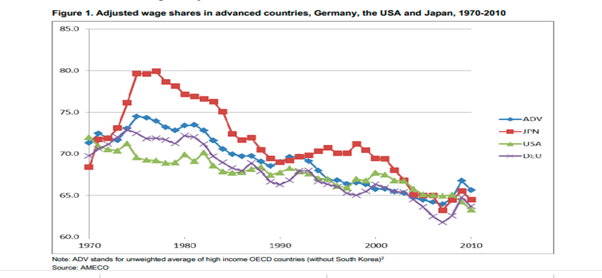

The IMF analysis only confirms plenty of other empirical work previously done. Indeed, wages as a share of GDP in all the major economies have been falling since the 1980s. Instead, profit share has risen. And over the period until 2019, inflation rates remained no more than 2-3% a year.

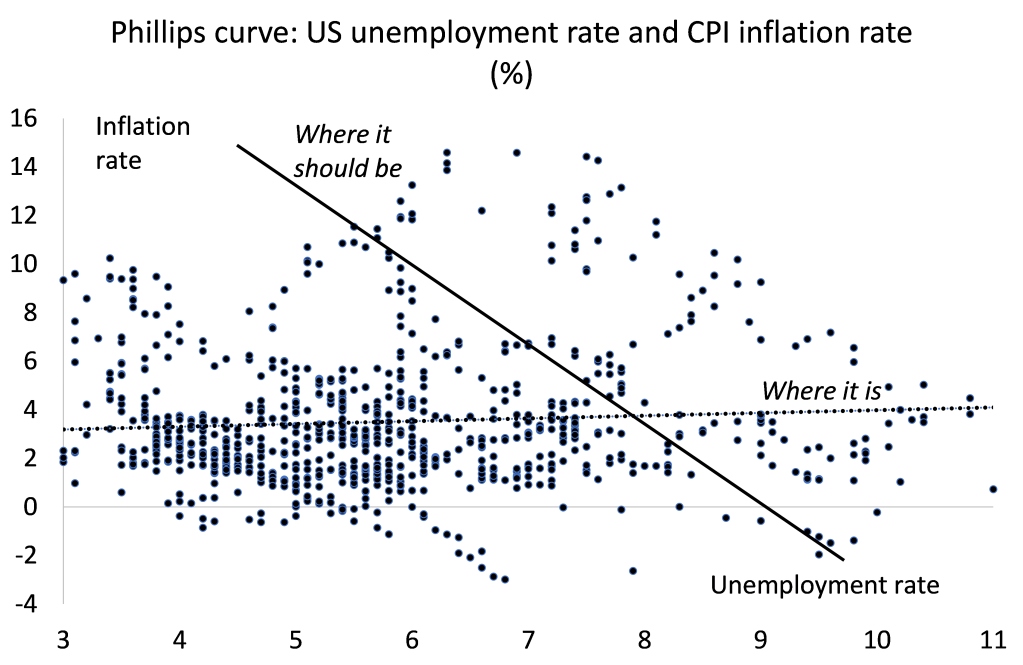

Also, there appears to be no inverse correlation between changes in wages, prices and unemployment – this classic Keynesian Phillips curve that claimed this relation has been shown to be false. Indeed, this was noted in the 1970s when unemployment and prices rose together. And the latest empirical estimates show the Phillips curve to be broadly flat – in other words, there is no correlation between wages, prices and unemployment. No wage-price spiral.

Despite this evidence refuting the wage-price spiral, mainstream economics and the official authorities continue to claim that this is the key risk to sustained inflation. The reason for doing so is not really because the economic prize-fighters for capitalism believe that wage rises cause inflation. It is because they want ‘wage restraint’ in the face of spiralling inflation in order to protect and sustain profits. To this aim they support central bank interest rate hikes that will accelerate economies into a slump – coming in the next year.

As Jay Powell, head of the US Federal Reserve put it: “in principle …, by moderating demand, we could … get wages down and then get inflation down without having to slow the economy and have a recession and have unemployment rise materially. So there’s a path to that.” Even more blatantly, Keynesian guru and FT columnist, Martin demanded: “What [central bankers] have to do is prevent a wage-price spiral, which would destabilise inflation expectations. Monetary policy must be tight enough to achieve this. In other words, it must create/preserve some slack in the labour market.

So the real aim of interest-rate hikes is not to stop a wage-price spiral but to raise unemployment and weaken the bargaining power of labour. I am reminded of the comment of Alan Budd, then chief economic adviser to British PM Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s: “There may have been people making the actual policy decisions… who never believed for a moment that this was the correct way to bring down inflation. They did, however, see that [monetarism] would be a very, very good way to raise unemployment, and raising unemployment was an extremely desirable way of reducing the strength of the working classes.”

No comments:

Post a Comment