In my last post, I described how Western capital is planning to take over and control Ukraine’s resources and exploit its labour force to the maximum in order to boost the profitability of both Ukraine’s domestic capitalists (oligarchs) and foreign multi-nationals.

However, there is a problem for Western capital and Ukraine’s oligarchs: it’s Russia. The war has already led to Russian forces gaining control of at least $12.4trn worth of Ukraine’s resources in energy (cola), metals and mineral deposits, apart from agricultural land. If Putin’s forces succeed in annexing Ukrainian land seized during Russia’s invasion, Kyiv would permanently lose almost two-thirds of its deposits. Moscow now controls 63% of Ukraine’s coal deposits, 11% of its oil, 20% of its natural gas, 42% of its metals, and 33% of its rare earths.

So any rebuilding effort funded by Western capital has a major obstacle. “Not only will Ukraine have lost a lot of its territory and its resources, but it would be constantly vulnerable to another onslaught by Russia,” said Jacob Kirkegaard, a fellow at the Washington-based Peterson Institute for International Economics. “No one in their right mind, a private company, would invest in the rest of Ukraine if this were to become a frozen conflict.” Ukraine has suffered continual bombing and military attacks with thousands of civilians dying and millions having to flee their homes and even leave the country. If Russia maintains its control of existing gains, the reconstruction of Ukraine as an independent state based funded by Western capital is put in jeopardy.

And many Russian-speaking Ukrainians and others will remain under the control of Russia. Ukraine’s working people are having their trade union rights and working conditions degraded by the nationalist Zelensky government. Under Putin’s Russia, it would even be worse. For in Russia, going on strike, demonstrating against the regime and organizing politically is already fraught with danger and even death (although Ukraine is heading the same way).

When the Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s, the elite in Russia, with the enthusiastic backing of US imperialism and Western economic advisers, moved quickly to dismantle the Soviet state sector. There was no attempt to introduce even ‘liberal democracy’. Much more important was to gain control of Russia’s resources and labour for private profit. The pro-capitalist hero Yeltsin quickly launched what has become called a ‘shock therapy’ introduction of markets and private capital. Prices were ‘liberalised’ and rapid privatisation began—all by presidential decree without any democratic mandate from the Russian people. Yeltsin pushed through a constitution which enshrined a powerful president with strong decree and veto powers.

When price controls were lifted, the prices for basic foodstuffs like bread and butter skyrocketed by as much as 500 percent in a matter of days. Large sections of the population sank into deep poverty almost overnight. By 1994, about 70 percent of the Russian economy was privatised. Yeltsin achieved this by selling off Russia’s assets for peanuts to a cabal of favoured people, now called ‘oligarchs’

During the seven years of the Yeltsin regime, Russia’s GDP fell 40% and numerous bouts of hyperinflation wiped out the savings of many Russian citizens. Crime was rampant; mafia ran protection schemes on businesses and officials demanded bribes. Life expectancy plummeted. Kleptocracy and extreme inequality were permanently embedded.

Alcoholic Yeltsin became extremely unpopular (his approval rating fell to just 10%). But the new cabal of oligarchs made sure he was re-elected in 1996 through a plan drawn up by Western strategists at that year’s Davos World Economic Forum and delivered through a massive campaign in the controlled media and through the sidelining of any opposition campaign (then mainly the Communists). However, the economy still struggled to recover and in 1998, the Russian government defaulted on $40 billion of short-term government bonds, devalued the ruble, and declared a moratorium on payments to foreign creditors.

This catastrophic default crippled the Yeltsin government and led to Yeltsin stepping down as president just over a year later. Yeltsin made way for his prime minister Vladimir Putin. Putin, a former KGB officer, promised to establish stability and prosperity with reforms. He restored discipline and order to the government; made the State Duma—Russia’s parliament—subordinate to his will; ended elections of regional governors and turned them into appointed officials, centralising authority; seized control of the media; and cracked down on any resistant oligarchs, exiling or imprisoning many of them.

A new elite emerged that replaced many of the oligarchs of the Yeltsin years. These were individuals close to Putin dating back to his days in the KGB or when he served as deputy mayor of St. Petersburg in the 1990s. Because of their close ties to Putin, they were able to gain control over important sectors of the Russian economy and became heads of state companies that grew following the nationalization of assets of many of the former Yeltsin-era oligarchs. Step-by-step Putin created a state of crony capitalism that was bolstered by the so-called siloviki—powerful figures from the security and military services—who were active participants in Putin’s increasingly corrupt system.

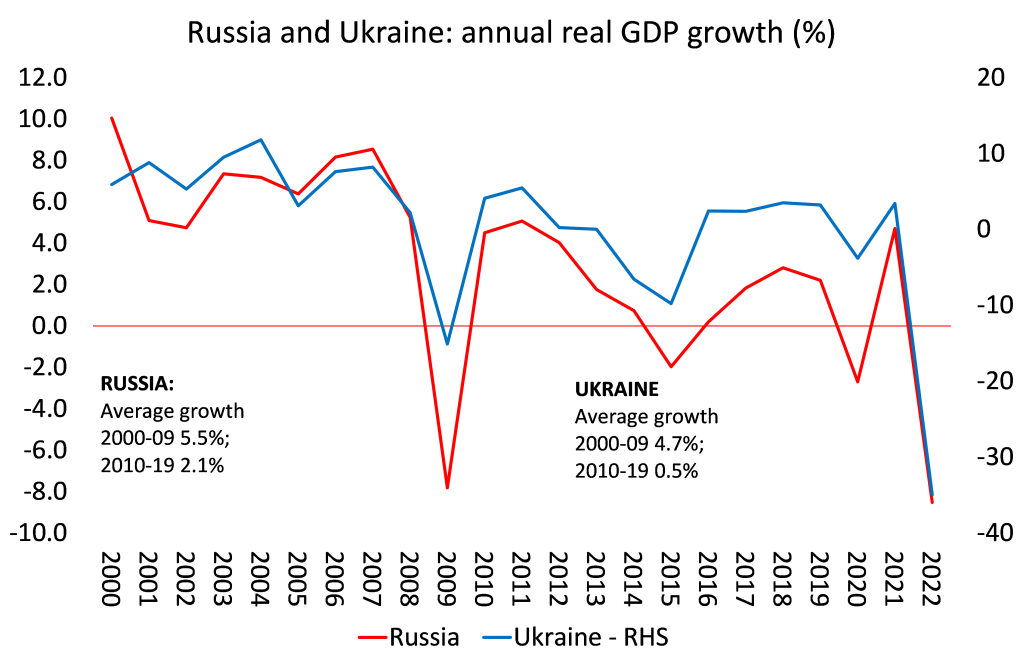

Putin was lucky. During his first two terms as president (2000–2004, and 2004–2008), the Russian economy prospered and the people shared to some extent in this brief economic boom. Average annual real GDP growth reached 5.5%. But this was only due to the commodity price boom that also helped many weaker capitalist economies like Chavez’s Venezuela or Lula’s Brazil. Oil prices surged from a low of $10 a barrel to a peak of $150 a barrel.

But those relatively ‘golden years’ based on energy exports came sharply to an end with the Great Recession of 2008-9 and the subsequent Long Depression of the 2010s when the commodities boom dissipated. Stagnation set in. Real GDP growth in the next decade averaged only 2%.

Foreign investment declined precipitously and capital flight accelerated to nearly 4% of annual GDP as the oligarchs (including Putin) spirited their ill-gotten gains into offshore havens or property in the UK, with the help of Western investment and legal companies and government tax incentives.

Productive investment growth was weak because the profitability of capital in Russia only slowly recovered from the ‘shock therapy’ years. This is graphically revealed by the trend in the profitability of Russian capital. After the ‘shock therapy’ economic collapse, profitability had recovered during the ‘golden years’ of Putin’s first two terms. But after 2007, profitability marked time; while economic growth crawled along.

So in Putin’s third term (after 2012), the regime became even more nationalist and autocratic, cracking down on any credible opposition with intimidation, force and even assassination. And 2014 saw a significant turning point. Putin promoted the 2014 Winter Olympics, which cost more than $50 billion—the most expensive Olympic Games ever. Much of the funding came from Putin’s billionaire cronies. So when the nationalist government in Ukraine launched its attacks on the Russian-speaking areas after the Maidan coup, Putin responded by annexing Crimea and providing active support for the separatists in the Donbas region. This boosted his popularity at home, turning attention away from the failure of the domestic economy, at least for a while, and his approval rating rocketed.

But the economy did not rocket. The West then applied economic sanctions against Russian business figures and sectors. Russia’s growth remained weak and below the growth rate in most developed countries. When adjusted for inflation, the average Russian was making less money in 2019 than in 2014.

Soon after he was first appointed president in 2000, Putin published an essay claiming that he wanted Russia to reach Portugal’s level of GDP per capita by the end of his two terms in office. Portugal was then the poorest EU member state. However, two decades later in 2021, Portugal’s GDP per capita in current dollars is twice as high as Russia’s. Despite the damage suffered by Portugal during the 2010 euro debt crisis, Russia has actually fallen further behind the Portuguese economy.

Amid stagnation, inequality has accelerated. According to joint research by the Higher School of Economics and the state-run VEB Bank, “the wealthiest 3 percent of Russians owned 89 percent of all financial assets in 2018.” The Moscow Times reports “the number of billionaires in Russia grew from 74 to 110 between mid-2018 and mid-2019, while the number of millionaires rose from 172,000 to 246,000.” According to Forbes’s rating, the total wealth possessed by Russia’s top 200 in 2019 was $15 billion higher than it had been in 2014.

In contrast, Rosstat reported last year that 14.3 percent of the population (21 million people) can be defined as poor. According to Yale economist Christopher Miller, Russians are getting poorer. The year “2018 marked the fifth straight year in which Russians’ inflation-adjusted disposable incomes fell.” Rosstat further reports that “almost two-thirds (63.5%) of Russian households only have enough money to buy food, clothes and other essential items.” The Russian Central Bank reported that 75 percent of the population is not able to save anything each month and almost one-third of those who manage to put some money into savings do so by skimping on food.

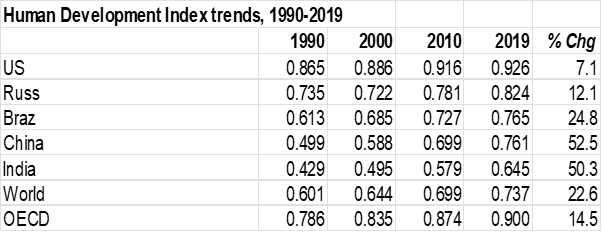

Just how badly Russia’s crony capitalist regime under Putin has performed for the average Russian is revealed in the UN’s human development index (HDI), which covers life expectancy, employment, incomes and other services. Russia’s HDI measure has grown the least of the major ‘emerging economies’ and is now way below the OECD average.

All this makes a joke of the arguments in the Western media that Putin’s regime is some sort of reversion to the Soviet state. For a start, Putin has often attacked ‘Bolshevism’ and, in particular the views of Lenin that nations like Ukrainians had a right to self-determination. Instead, Putin has turned to the feudal imperialism of Russia’s Peter the Great as his model for the invasion of Ukraine. Putin has eulogized Peter’s conquests in the Great Northern War and praised him for “returning” historically Russian lands. “It seems that it has fallen to us, too, to return (Russian lands),” Putin commented. For him, Ukraine is not a nation but part of Russia, which the nationalist in Kyev and Western powers are tryng to separate.

The irony is that Putin’s imperialist ambitions for control of the peripheral countries of the former Soviet Union are not backed up by a modern imperialist economy. Russia is not in the imperialist league, as I have shown in previous posts. Russia is no super power, economically or politically. Its total wealth (including labour and natural resources) is way down the league compared to the US and the G7 (red bars). And even its supposed military might has been exposed as a paper tiger.

The Russia economy remains a ‘one-trick pony’, depending on oil and gas that make up more than half its exports before the war started, with the rest being grain, chemicals and metals – no advanced technology exports. That means that far from extracting surplus value through trade with other countries, instead, the more advanced capitalist economies and their multi-nationals get net transfers of surplus value from Russia.

Putin may think Russia can be an imperialist power, but the economic reality is that Russia is just a large peripheral economy outside the US-led imperialist bloc like Brazil, China, India, South Africa, Turkey, Egypt etc – if with a larger military than most. Seriously opposing that bloc leads to conflict, as China now faces.

No comments:

Post a Comment