by Michael Roberts

Last week, Ukraine’s foreign private creditors agreed to the

country’s request for a two-year freeze on payments on about $20bn of

foreign debt. This would enable Ukraine to avoid defaulting on its

overseas borrowings. Unlike other ‘emerging economies’ in debt

distress, it seems that foreign bondholders are happy to help Ukraine

out – if only for two years. The move will save Ukraine $6bn over the

period, helping to reduce pressure on central bank reserves, which slid

by 28 per cent year-to-date, despite significant foreign aid.

Ukraine’s economy is, not surprisingly, in a desperate state. Real GDP is projected to decline by more than 30% in 2022 and the unemployment rate is at 35% (Constantinescu et al. 2022, Blinov and Djankov 2022, National Bank of Ukraine 2022). “We are grateful for the private sector support of our proposal in such terrible times for our country,” responded Yuriy Butsa, Ukraine’s deputy finance minister, “I’d like to emphasise that the support we’ve received during this transaction is hard to underestimate . . . We will stay fully engaged with the investment community further on and hope for their involvement in the financing of the rebuilding of our country after we win the war,” Butsa said.

Here Butsa reveals the price to pay for this limited largesse by foreign creditors.: the accelerating demand of foreign multi-nationals and governments to take control of Ukraine resources and bring them under the control of foreign capital without any restrictions and limitations.

In a past post, I had outlined the plan to privatise and hand over the vast agricultural resources of Ukraine to foreign multi-nationals. And for several years now, a series of reports by the Oakland Institute economic observatory has documented the takeover of foreign capital. Much of what is below comes from Oakland.

Post-Soviet Ukraine, with its 32 million arable hectares of rich and fertile black soil (known as “cernozëm”), has the equivalent of one-third of all existing agricultural land in the European Union. The “breadbasket of Europe,” as it is called, had an annual production of 64 million tons of grain and seeds, among the world’s largest producers of barley, wheat and sunflower oil (for the latter, Ukraine produces about 30 percent of the world total).

As I explained in my previous post, the planned takeover of Ukraine’s resources partly provoked the conflict: the semi-civil war, the Maidan revolt and the annexation of Crimea by Russia. As the Oakland Institute has outlined, to limit unrestrained privatization, a moratorium on the sale of land to foreigners had been imposed in 2001. Since then, the repeal of this rule has been a main goal of Western institutions. As early as 2013, for instance, the World Bank provided an $89 million loan for the development of a deed and land title program needed for the commercialization of state-owned and cooperative land. In the words of a 2019 World Bank paper the aim was an “accelerating of private investment in agriculture.” That agreement, denounced at the time by Russia as a backdoor to facilitating the entry of Western multinationals, includes the promotion of “modern agricultural production … including the use of biotechnologies,” an apparent opening towards GMO crops on Ukrainian fields.

Despite the moratorium on land sales to foreigners, by 2016, ten multinational agricultural corporations had already come to control 2.8 million hectares of land. Today, some estimates speak of 3.4 million hectares in the hands of foreign companies and Ukrainian companies with foreign funds as shareholders. Other estimates are as high as 6 million hectares. The moratorium on sales, which the US State Department, IMF and World Bank had repeatedly called to be removed, was finally repealed by the Zelensky government in 2020, ahead of a final referendum on the issue scheduled for 2024.

Now with war grinding on, Western governments and corporations are stepping up their plans to incorporate Ukraine and its resources into the capitalist economies of the West.On July 4 and 5, 2022, top officials from the US, EU, Britain, Japan, and South Korea met in Switzerland for a so-called “Ukraine Recovery Conference.”

The URC’s agenda was explicitly focused on imposing political changes on the country – namely, “strengthening the market economy“, “decentralization, privatization, reform of state-owned enterprises, land reform, state administration reform,” and “Euro-Atlantic integration.” The agenda was really a follow-up to the 2018 Ukraine Reform Conference which had emphasized the importance of privatizing most of Ukraine’s remaining public sector, stating that the “ultimate goal of the reform is to sell state-owned enterprises to private investors”, along with calls for more “privatization, deregulation, energy reform, tax and customs reform.” Lamenting that the “government is Ukraine’s largest asset holder,” the report stated, “Reform in privatization and SOEs has been long awaited, as this sector of the Ukrainian economy has remained largely unchanged since 1991.”

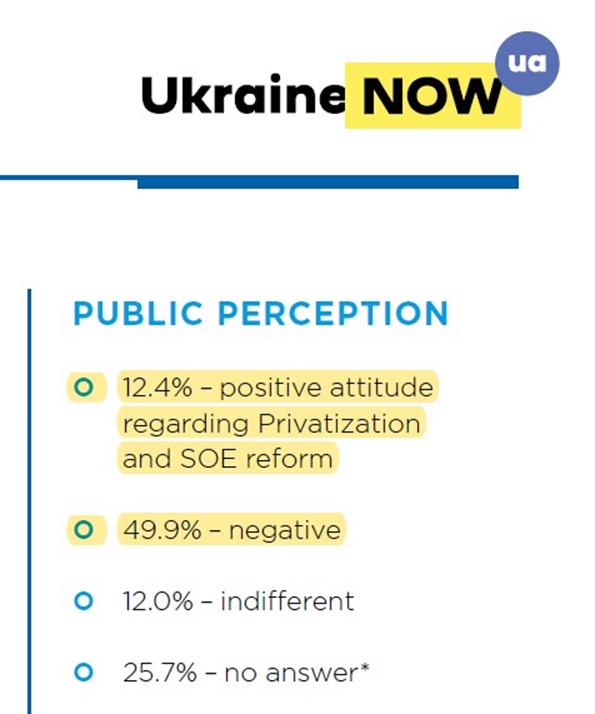

The irony is that the 2018 URC plans were opposed by most Ukrainians. A public opinion poll found that just 12.4% supported privatization of state-owned enterprises (SOE), whereas 49.9% opposed it. (An additional 12% were indifferent, whereas 25.7% had no answer.)

However, war can make all the difference. In June 2020, the IMF approved an 18-month, $5 billion loan program with Ukraine. In return, the Ukraine government lift[ed] the 19-year moratorium on the sale of state-owned agricultural lands, after sustained pressure from international finance institutions.. Olena Borodina with the Ukrainian Rural Development Network commented that, “the agribusiness interests and oligarchs will be the primary beneficiaries of such reform…[This] will only further marginalize smallholder farmers and risks severing them from their most valuable resource.”

And now July’s URC has re-emphasised its plans to take over the Ukraine economy for capital, with the full endorsement of Zelensky government. At the conclusion of the meeting, all governments and institutions present endorsed a joint statement called the Lugano Declaration. This declaration was supplemented by a “National Recovery Plan,” which was in turn prepared by a “National Recovery Council” established by the Ukrainian government.

This plan advocated for an array of pro-capital measures, including “privatization of non critical enterprises” and “finalization of corporatization of SOEs” (state-owned enterprises) – identifying as an example the selling off of Ukraine’s state-owned nuclear energy company EnergoAtom. In order to “attract private capital into banking system,” the proposal likewise called for the “privatization of SOBs” (state-owned banks). Seeking to increase “private investment and boost nationwide entrepreneurship,” the National Recovery Plan urged significant “deregulation” and proposed the creation of “‘catalyst projects’ to unlock private investment into priority sectors.”

In an explicit call for slashing labour protections, the document attacked the remaining pro-worker laws in Ukraine, some of which are a holdover of the Soviet era. The National Recovery Plan complained of “outdated labor legislation leading to complicated hiring and firing process, regulation of overtime, etc.” As an example of this supposed “outdated labor legislation,” the Western-backed plan lamented that workers in Ukraine with one year of experience are granted a nine-week “notice period for redundancy dismissal,” compared to just four weeks in Poland and South Korea.

In March 2022, the Ukrainian parliament adopted emergency legislation allowing employers to suspend collective agreements. Then in May, it passed a permanent reform package effectively exempting the vast majority of Ukrainian workers (those at businesses with fewer than 200 employees) from Ukrainian labor law. Documents leaked in 2021 showed that the British government coached Ukrainian officials on how to convince a recalcitrant public to give up workers’ rights and implement anti-union policies. Training materials lamented that popular opinion towards the proposed reforms was overwhelmingly negative, but provided messaging strategies to mislead Ukrainians into supporting them.

While workers’ rights are to be removed in the ‘new Ukraine’, in contrast the National Recovery Plan aims to help corporations and the wealthy by lowering taxes. The plan complained that 40% of Ukraine’s GDP came from tax revenue, calling this a “rather high tax burden” compared to its model example of South Korea. It thus called to “transform tax service,” and “review potential for decreasing the share of tax revenue in GDP.” In the name of “EU integration and access to markets,” it likewise proposed “removal of tariffs and non-tariff non-technical barriers for all Ukrainian goods,” while simultaneously calling to “facilitate FDI [foreign direct investment] attraction to bring the largest international companies to Ukraine,” with “special investment incentives” for foreign corporations.

In addition to the National Recovery Plan and the strategic briefing, the July 2022 Ukraine Recovery Conference presented a report prepared by the company Economist Impact, a corporate consulting firm that is part of The Economist Group. The Ukraine Reform Tracker pushed to “increase foreign direct investments” by international corporations, not invest resources in social programs for the Ukrainian people. The Tracker report emphasized the importance of developing the financial sector and called for “removing excessive regulations” and tariffs. It called for further “liberalising agriculture” to “attract foreign investment and encourage domestic entrepreneurship,” as well as “procedural simplifications,” to “make it easier for small and medium enterprises” to “expand by purchasing and investing in state-owned assets,” thereby “making it easier for foreign investors to enter the market post-conflict.”

The Ukraine Reform Tracker presented the war as an opportunity to impose the take over by foreign capital. “The post-war moment may present an opportunity to complete the difficult land reform by extending the right to purchase agricultural land to legal entities, including foreign ones,” the report stated. “Opening the path for international capital to flow into Ukrainian agriculture will likely boost productivity across the sector, increasing its competitiveness in the EU market,” it added. “Once the war is over, the government will also need to consider substantially lowering the share of state owned banks, with the privatisation of Privatbank, the country’s largest lender, and Oshchadbank, a large processor of pensions and social payments,” it insisted.

Elsewhere there are less explicit pro-capital polices offered by semi-Keynesian Western economists. In a recent compilation by the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), various economists have proposed Macroeconomic Policies for Wartime Ukraine. In this the authors “emphasise at the outset that Ukraine’s crisis is not a setting for a typical macroeconomic adjustment programme. ie not the usual IMF fiscal austerity and privatisation demands. But after many pages, it becomes clear that there is little difference in their proposals than those of the URC. As they say “the aim should be to pursue extensive radical deregulation of economic activity, avoid price controls, facilitate matching of labour and capital, and enhance the management of seized Russian and other sanctioned assets.“

The takeover of Ukraine by capital (mainly foreign) will thus be completed and Ukraine can start paying back its debts and providing new profits for Western imperialism.

No comments:

Post a Comment