The IRA and the four horsemen of the climate apocalypse

by Michael Roberts

The announcement that US President’s Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act

(IRA) has got the backing of pro-business, coal-mining owner Democratic

Senator Manchin has been greeted with a wave of optimism that the US

target of cutting carbon emissions in half before the end of this decade

(or 40% compared with 2005 levels), can be met. “This bill will

really turbocharge that transition to clean energy, it will transform

markets where already solar PV, wind and batteries are in many cases

cheaper than incumbent fossil fuels,” said Anand Gopal, executive director of policy at Energy Innovation, an open source research body. “Increasingly

I’m more optimistic that keeping the temperature rise under 2C (3.6F)

is more reachable. 1.5C is a stretch goal at this point.”

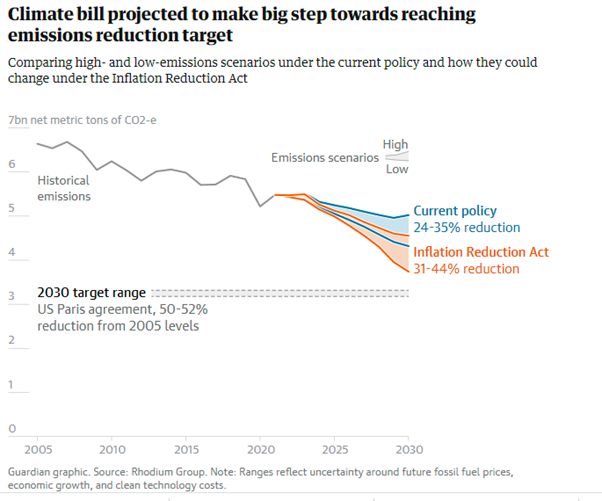

The bill will cut US emissions by between 31% and 44% below 2005 levels by 2030, according to Rhodium Group, a non-partisan research firm. A separate analysis by Energy Innovation, another research house, has found a similar reduction, of between 37% and 41% this decade.

But will it do the trick of saving the planet? First, the IRA has to get through Congress and even after a huge watering down of the bill to accommodate Manchin, there is still no certainty that it will get past a Republican opposition. As it is, the bill actually allows for an expansion of oil and gas drilling in national parks and land as a sop to Manchin. There may be yet more concessions to the fossil fuel lobby.

Then there are actual measures proposed in the IRA. “This is a massive turning point,” argues Leah Stokes, a climate policy expert at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “This bill includes so much, it comprises nearly $370bn in climate and clean energy investments. That’s truly historic. Overall, the IRA is a huge opportunity to tackle the climate crisis.” But is it? Much of the bill is really tax credits to companies to invest in clean energy projects as well as a rebate of up to $7,500 for Americans who want to buy new electric vehicles. There is $9bn to retrofit houses to make them more energy efficient, tax credits for heat pumps and rooftop solar and a $27bn “clean energy technology accelerator” to help deploy new renewable technology. A further $60bn would go towards environmental justice projects and there is a new program to reduce leaks of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, from oil and gas drilling. Much of this is not direct public investment in climate projects but incentives to the private sector to do the right thing. The capitalist sector is being left to deliver on these targets.

And that’s the US. Elsewhere in the world, investment in meeting the already very modest target of limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5C by 2030 is looking way too little. Indeed, the opposite is happening. For example, because of the threatened loss of energy in Europe from blocked Russian imports, the EU parliament has voted to designate gas and nuclear as sustainable! The need for energy to heat homes and fuel industry and transport after the Ukraine crisis has come into conflict with the aim to save the planet. The irony is that a global recession would reduce the demand for fossil fuel energy globally and so help reduce the impact on the planet.

And then there is the war itself. The military sector globally is the largest emitter of greenhouse gases in economies. And yet Nato’s secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg promised the alliance’s Madrid summit recently that there would be a nearly eightfold expansion in forces on high alert to 300,000. And member countries are also hiking defence spending to at least 2 per cent of GDP , “which is increasingly considered a floor, not a ceiling”. Russia’s military spending in 2021 hit $66bn, says the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. But even then, the US was spending $801bn a year and other Nato members about $363bn. NATO will be outspending Russia’s military by about 10 to one in the region, notes Dan Plesch of SOAS, University of London.

What the war and sky-high energy prices have brought home is that carbon pricing is no answer to controlling global warming. In effect, we’ve now got a global carbon tax, inflicting real hardship on people around the world without necessarily doing much to speed the transition from carbon.

I have argued against this ‘market solution’ in previous posts. Instead we need a global plan of public investment into things society does need, like renewable energy, organic farming, public transportation, public water systems, ecological remediation, public health, quality schools and other currently unmet needs. And it could equalize development the world over by shifting resources out of useless and harmful production in the North and into developing the South, building basic infrastructure, sanitation systems, public schools, health care. At the same time, a global plan could aim to provide equivalent jobs for workers displaced by the retrenchment or closure of unnecessary or harmful industries. None of those outcomes are offered by the IRA.

The other counter to the optimism now again coming forth on abating climate change and global warming is the risk of what is called in statistics a ‘fat tail’ in the probability of where global temperatures are likely to reach in the next few decades. The IPCC tends to look at the most probable outcome ie say a 2.5C increase by 2050. That’s bad enough. But there is still a reasonable probability that it could be much worse. Last year’s IPCC report suggested that if atmospheric CO doubles from pre-industrial levels – something the planet is halfway towards – then there is a roughly an 18% chance that temperatures will rise beyond 4.5°C. What would be the impact of that ‘fat tail’ coming through?

Well, just on GDP terms, one study shows that “a persistent increase in average global temperature by 0.04 °C per year, in the absence of mitigation policies, reduces world real GDP per capita by more than 7 percent by 2100. On the other hand, abiding by the Paris Agreement goals, thereby limiting the temperature increase to 0.01 °C per annum, reduces the loss substantially to about 1 percent.” The estimated losses would increase to 13 percent globally if country-specific variability of climate conditions were to rise commensurate with current annual temperature increases of 0.04 °C.

But that’s just the loss of GDP. The point is that if global temperatures were to reach above the optimistic 1.5C or 2.0C increase and beyond, the impact on the planet is exponential not gradual. “There are plenty of reasons to believe climate change could become catastrophic, even at modest levels of warming,” said lead author Dr Luke Kemp from Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, (https://www.cser.ac.uk/). Then what one study has called ‘the four horsemen of the climate apocalypse’ will appear, namely “famine and malnutrition, extreme weather, conflict, and vector-borne diseases.” The ‘fat tail’ of probability would deliver rising temperatures that pose a major threat to global food supply, with increasing probabilities of “breadbasket failures” as the world’s most agriculturally productive areas suffer collective meltdowns. Hotter and more extreme weather could also create conditions for new disease outbreaks as habitats for both people and wildlife shift and shrink.

The modelling in this study concluded that areas of extreme heat (i.e. an annual average temperature of over 29 °C), could cover two billion people by 2070. These areas are not only some of the most densely populated, but also some of the most politically fragile. “Average annual temperatures of 29 degrees currently affect around 30 million people in the Sahara and Gulf Coast,” said co-author Chi Xu of Nanjing University. “By 2070, these temperatures and the social and political consequences will directly affect two nuclear powers, and seven maximum containment laboratories housing the most dangerous pathogens. There is serious potential for disastrous knock-on effects,” he said.

The IRA may make some small inroads into emissions reduction in the US, if fully implemented (and as I say, there are serious doubts about that). But globally, there is little sign that global warming can be stopped at the Paris target; more likely global temperatures will rise above a 2C increase and beyond, as governments struggle to reconcile the need for energy at reasonable prices and reducing emissions (unless a major global slump solves the contradiction for a while). The four horsemen of the climate apocalypse are on the horizon.

No comments:

Post a Comment