Last week the World Bank issued its latest Global Economic Prospects. The WB economists reckon that the world economy "is stabilising" in 2024, the first time in three years. The world economy avoided an outright recession in 2023 that many predicted (including me – to some degree) and is now making a 'soft landing'. Global real GDP growth will be 2.6% in 2024, the same as 2023 and will rise slightly to 2.7% next year.

The term ‘soft landing’ is somewhat odd. I suppose it means that the world economy has not crashed into the runway, but instead lightly settled down. But really, there has been no landing at all – if we mean by that a slump or contraction in real GDP globally. Anyway, to use another aphorism, the world economy is really ‘a curate’s egg’, an old-fashioned term to described something that is partly bad and partly good, or more exactly something that is obviously and entirely bad, but is described out of politeness as nonetheless having good features that might redeem it.

The reality is that, despite no overall contraction in real GDP globally, several major economies continue to stagnate at best and world growth will remain well under the pre-pandemic average rate of 3.1% - even though that global figure includes faster-growing India, Indonesia and China. As the World Bank put it: "countries that collectively account for more than 80% of the world’s population and global GDP would still be growing more slowly than they did in the decade before COVID-19." And, worse, "one in four developing economies is expected to remain poorer than it was on the eve of the pandemic in 2019. This proportion is twice as high for countries in fragile- and conflict-affected situations." The WB economists conclude that “the income gap between developing economies and advanced economies is set to widen in nearly half of developing economies over 2020-24."

When we drill down to growth rates in each of the major economies, the ‘soft landing’ looks even more inappropriate as a term. Take the US economy, the best performing of the top seven capitalist economies (G7). After the ‘sugar rush’ year of recovery in 2021following the pandemic slump of 2020, there was actually a ‘technical recession’ (i.e. two successive quarterly contractions in real GDP) in 2022. Then 2023 saw modest growth, which appeared to accelerate in the second half. However, there was a significant slowdown in the first quarter of this year, with the US economy expanding at its slowest rate since the recession of early 2022.

Looking ahead, various forecasts for the qoq increase in the current quarter (Q2 2024) are about 0.4-0.5%.

And that’s the US. Performance was much worse in the other G7 economies. The Eurozone as a whole was a total write-off in 2023.

As for Japan, a ‘soft landing’ has clearly not been achieved.

And let’s not leave out Canada, the smallest G7 economy. The economy was basically stagnant in the last half of 2023.

You find the same story in Australia, Sweden and the Netherlands. As for the British economy, it is the worst performing in the G7, rivalling even Italy.

Sure, some of the large ‘emerging’ economies are doing ok. Among the so-called BRICS, India is growing at 6% a year (if you can believe the official figures), China at 5% a year and the Russian war economy at 3% a year. But Brazil is crawling along at well under 1% while South Africa is in a slump. And many other poorer, smaller economies in the so-called Global South are in deep distress.

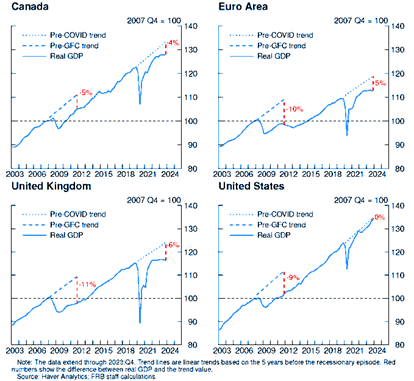

What the latest data reveal is that the major economies remain in what I have called a Long Depression, namely where after each slump or contraction (2008-9 and 2020), there follows a lower trajectory of real GDP growth – the previous trend is not restored. The trend growth rate before the global financial crash (GFC) and the Great Recession is not returned to; and the growth trajectory dropped even further after the pandemic slump of 2020. Canada is still 9% below the pre-GFC trend; the Eurozone is 15% below; the UK 17% below and even the US is still 9% below.

The world economy is now stuck in what the IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva called the ‘tepid twenties’. The World Bank economists reckon that the global economy is on track for “its worst half-decade of growth in 30 years”.

And if we drill down into the Eurozone itself, we get the full picture of the disaster of the German economy, previously the manufacturing powerhouse of Europe. Since 2021, there have been five quarters of contraction out of 12 and only one quarter higher than 1%.

That’s a performance worse than permanently stagnant Japan. Germany’s manufacturing sector activity is not achieving a soft landing – not even a curate’s egg. It is a total car crash, nearly back to the pandemic of 2020.

No wonder German workers’ real wages have plummeted in the last four years – down a staggering 6% since the end of the pandemic in 2020, despite a modest recovery in the last half of 2023. And no wonder that the ‘hard right’ parties in Germany have done so well in the recent EU Assembly elections.

Meanwhile inflation rates in the major economies are looking sticky. Prices have risen on average 20% since the end of the pandemic. The rate of that rise slowed through 2023. But now the rates are no longer falling, and in some countries, they are picking up again. The EZ inflation rate is still above the European Central Bank (ECB) target of 2%. Indeed, it rose in May to 2.6% yoy. Core inflation (which excludes food and energy) also rose to 2.9% yoy. Indeed, the ECB has raised its forecast for annual inflation for 2024 to 2.5% and for next year to 2.2%. It does not see its 2% inflation target being met before 2026! At the beginning of 2021, inflation was just 0.9% and it peaked at 10.6% in October 2022. That means, even if the ECB forecasts are proved right, the ECB target will have been breached for nearly five years! So much for the efficacy of central bank monetary policy.

This month, the ECB tentatively cut its interest rate by 25bp to 4.25%, the first cut since the ECB started raising rates from 0.5% in July 2022 to (supposedly) curb inflation. That’s because it is worried that the Eurozone economy cannot sustain any economic recovery while the cost of borrowing to invest or spend remains so high. In contrast, the US Federal Reserve held its policy interest-rate unchanged at its last meeting. It remains at a 23-year high of 5.5%. Again, contrary to the hopes of the Fed, US consumer price inflation has stopped falling. The Fed members now expect inflation to remain near 3% and for the 2% inflation target also not to be met before 2026!

Much is made of the low unemployment rate and net growth in jobs in the US. Officially, the US economy added 272K jobs in May 2024, the most in five months. But the unemployment rate rose to 4% in May. And all the net rise in jobs comes from part-time work. Part-time jobs rose 286k in May, but full-time jobs fell 625k. Indeed, in the last 12 months, full-time jobs have shrunk by 1.1m while part-time jobs rose 1.5m. After taking into account inflation, real weekly earnings are still some 7% below where they were four years ago and have been flat in the last year. As a result, the number of Americans doing multiple jobs hit 8.4m in May, rise of 3m since 2020. It needs two jobs to make ends meet. So the US economy is not shooting along as the mainstream pundits claim. The acceleration in growth in 2023 seems to be over.

The main reason for slowing growth in the US in the first quarter of this year was a drop-off in growth in the consumption of goods and business investment (the boom in building offices and factories is over). And there are two reasons for that. First, there has been an absolute fall in corporate profits, down $114bn in the non-financial sector. And second is the high Fed interest rate, which means the continuance of high mortgage rates for households and debt servicing costs for many weak unprofitable companies. That's a recipe for more bankruptcies ahead.

We all read about the huge profits being made by the so-called Magnificent Seven of social media and technology behemoths. But it only these companies that are doing well. The market capitalization of 10 largest US stocks accounts for over 13% of global stock market value This is way above the Dot-com bubble peak of 9.9% in March 2000. In a blaze of unprecedented rise in stock market price, Nvidia, AI chip company has become the most highly valued in the world, surpassing Apple and Microsoft.

In contrast, 42% of US small-cap companies are unprofitable, the most since the 2020 pandemic when 53% of small caps were losing money. Small-cap companies are struggling.

There is no escape for stagnant domestic economies through increased trade. Global trade has been floundering for years and suffered a sharp downturn during the pandemic slump. World trade actually contracted in 2023.

Source: CPD

Again, no wonder the US and its allies have launched at attack on China’s export success by imposing tariffs and other sanctions on Chinese goods. To combat that, China has switched (been forced?) into other markets rather than the US and Europe.

But the great tariff war has hardly started. Recent measures by Biden are going to be ‘trumped’ in 2025 if ‘the Donald’ is re-elected this year. Trump plans to impose a 10 per cent levy on all US imports and a 60 per cent tax on goods coming from China. The tariffs will fund his plans to extend a series of tax cuts, which he introduced while president in 2017, beyond 2025. Indeed, Trump is talking of imposing tariffs sufficiently high to allow him to end income tax altogether!

A recent study suggests that Trump’s policies are “sharply regressive tax policy changes, shifting tax burdens away from the well-off and towards lower-income members of society”. The paper, by Kim Clausing and Mary Lovely, puts the cost of existing levies plus Trump’s tariff plans for his second term at 1.8 per cent of GDP. It warns that this estimate “does not consider further damage from America’s trading partners retaliating and other side effects such as lost competitiveness.”

This calculation “implies that the costs from Trump’s proposed new tariffs will be nearly five times those caused by the Trump tariff shocks through late 2019, generating additional costs to consumers from this channel alone of about $500bn per year,” the paper said. The average hit to a middle-income household would be $1,700 a year. The poorest 50 per cent of households, who tend to spend a bigger proportion of their earnings, will see their disposable income dented by an average of 3.5 per cent.

Mainstream economists continue to claim that the major economies have achieved a ‘soft landing’ and things are now on an even keel. But a recent survey found that 56% of Americans thought the US was in a recession and 72% thought inflation was rising. Economists like Paul Krugman reckon European and American households seem to be ‘out of touch’. But who is really out of touch? American households or the expert economists?

No comments:

Post a Comment