The semi-annual meeting of the IMF and World Bank starts this week. The agencies and their invited guests will discuss the state of the world economy and the challenges ahead and present policy solutions. At least that’s the ostensible idea.

Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the IMF, has just been re-appointed for another five-year term unopposed. In previewing the meeting, she outlined how the IMF sees the world economy in 2024 and through the rest of this third decade of the 21st century. She offered a dismal analysis. Ahead was a “sluggish and disappointing decade”. Indeed, “without a course correction, we are … heading for the Tepid Twenties”. Her comments prefaced the release of the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook including its long-term forecast for the world economy.

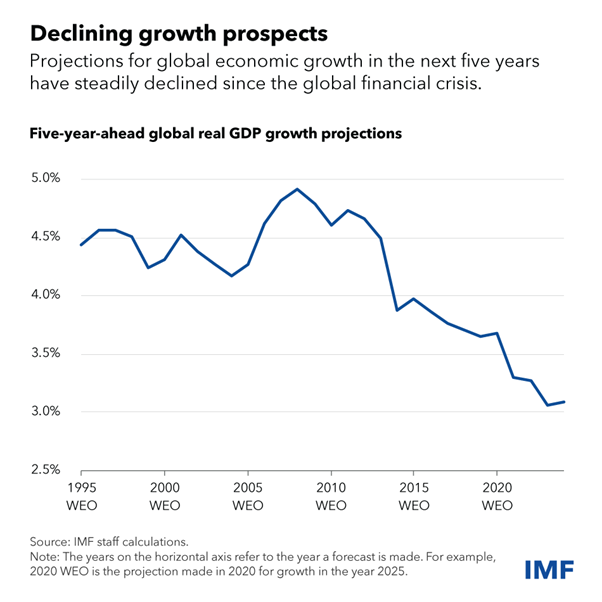

It makes for sober reading. Let me quote: “Faced with several headwinds, future growth prospects have also soured. Global growth will slow to just above 3 percent by 2029, according to five-year ahead projections. Our analysis shows that growth could drop by about a percentage point below the pre-pandemic (2000-19) average by the end of the decade. This threatens to reverse improvements to living standards, and the unevenness of the slowdown between richer and poorer nations could limit the prospects for global income convergence.”

“A persistent low-growth scenario, combined with high interest rates, could put debt sustainability at risk—restricting the government’s capacity to counter economic slowdowns and invest in social welfare or environmental initiatives. Moreover, expectations of weak growth could discourage investment in capital and technologies, possibly deepening the slowdown. All this is exacerbated by strong headwinds from geo-economic fragmentation, and harmful unilateral trade and industrial policies.”

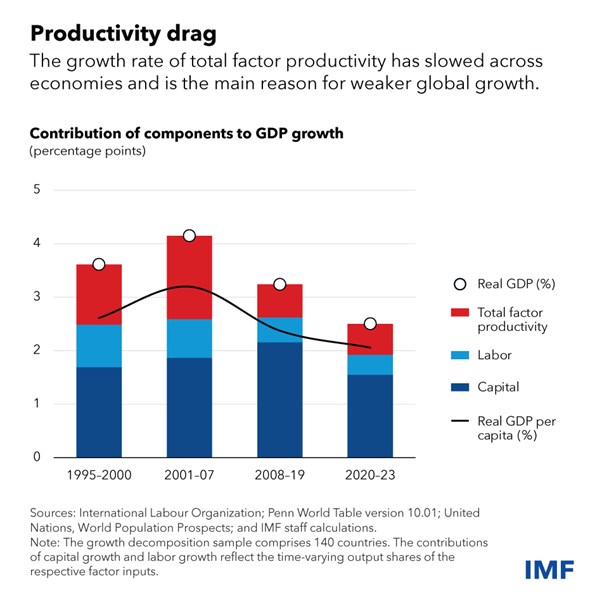

The main driver of growth in world output is through the increased productivity of labour and that has been slowing. And this “is likely to continue to decline, driven by challenges such as the increasing difficulty of coming up with technological breakthroughs, stagnation in educational attainment, and a slower process by which less developed economies can catch up with their more developed peers.”

The IMF is making it starkly clear that the capitalist mode of production is failing to deliver on increased productivity, essential to meet the social needs of 8bn humans. And why? First, because innovation is fading. In mainstream economics, this is measured by what is called total factor productivity (TFP), the amount of productivity that cannot be explained by investment in means of production or in employing labour – it’s a residual to complete the total level of productivity. In this decade so far, global TFP growth has slowed to its lowest rate since the 1980s.

The IMF is also saying that failure to invest sufficiently in what capitalist economists like to call ‘human capital’ has led to no improvement in the skills of the global workforce. And most interestingly, the IMF admits that the gap between the rich, technically more advanced capitalist economies (the imperialist bloc in effect) and the poor, less advanced periphery, where 80% of humanity lives, is not narrowing at all – contrary to the continual claims of many mainstream economic studies.

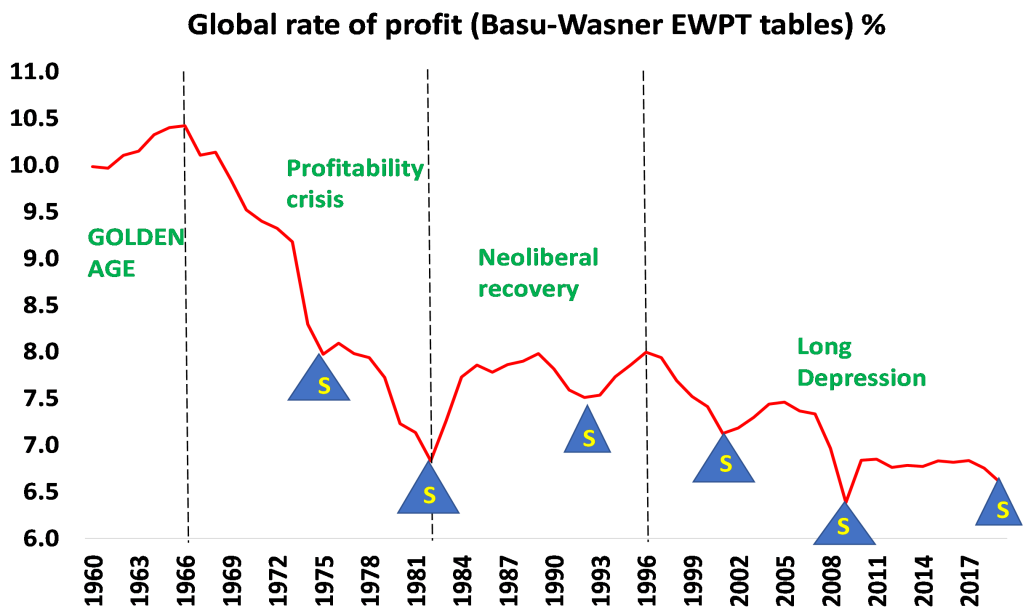

The world economy’s expansion has been slowing down particularly since the end of the Great Recession of 2008-9, the IMF says, echoing my own analysis of what I have called a Long Depression in the major capitalist economies.

In particular, business investment, the major driver of economic growth in capitalist economies, has “tumbled after 2008, and in 2021 it fell by about 40 percent of its pre-global-financial-crisis trend”. And what is the reason for this decline? The IMF says: “since 2008, Tobin’s q, an indicator of firms’ future productivity and profitability expectations, has decreased by 10 to 30 percent on average, contributing to the bulk of the explained decline in investment in both advanced and emerging market economies.” This is a roundabout way of saying that investment growth by capitalist companies has slowed because they have not been getting the levels of profitability they expected, as the graph below shows.

So slowing growth in global real GDP, according to the IMF, is down to: 1) slowing growth in the world’s available labour force, projected to fall to just 0.3% a year; 2) stagnant business investment; and 3) weakening innovation. By the end of this decade (and this assumes no major global slump, as suffered in 2008 and 2020), global growth will fall to 2.8% a year for the first time since 1945.

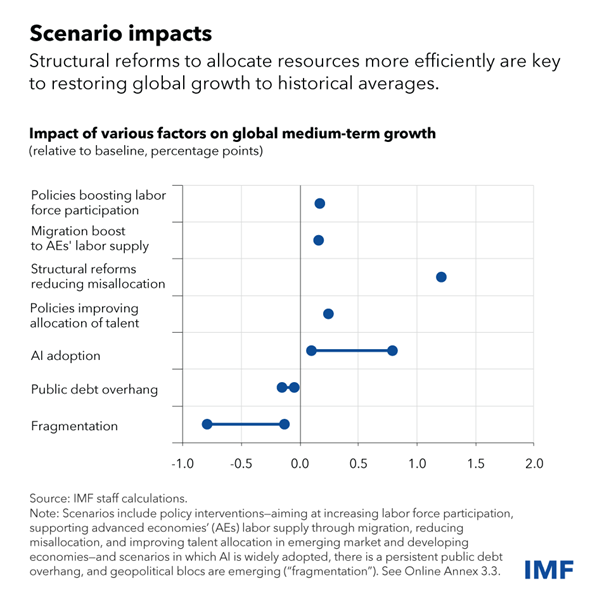

What are the components of this second decade of depressionary slowdown, according to the IMF? The main factor up to now has been that ‘resources’ have been ‘mis-allocated’. What the IMF means is that the free market system is not allocating the means of production, technological innovation and labour supply to the most productive-enhancing sectors. That misallocation is losing 1.3% pts of global growth each year, the IMF estimates. The IMF does not say this, but when capitalist investment increasingly goes into financial and property speculation, military spending, advertising and marketing, etc, it’s not surprising that there is such a ‘misallocation’ of resources that holds back productivity growth.

The other damaging factor to future growth that the IMF identifies is the ‘fragmentation’ of global trade and investment, as the major economic powers move towards protectionism, tariffs, bans on exports and business operations; and the imperialist powers led by the US seek to weaken and strangle those countries not ‘towing the line’, like Russia and China. The breaking-up of formerly globalised ‘free trade’ into competing blocs, the IMF reckons will reduce annual global growth by up to 0.7% pts.

What to do? After its dismal analysis of the future, the IMF proposes to solve the problems through more labour participation (women going to work) and more immigration (see my recent post), but mostly by the usual package of mainstream economic measures: “market competition, trade openness, financial access, and labor market flexibility” ie in other words, more free movement of capital (reduced regulation) and a reduction in labour rights (called ‘flexibility’). The IMF is really saying that the answer is to boost profitability by exploiting labour more and by allowing big capital to move freely across the globe. The IMF has proposed such measures nearly every year with little result.

As for AI, the IMF says: “the potential of AI to boost labor productivity is uncertain but potentially substantial as well, possibly adding up to 0.8 percentage points to global growth, depending on its adoption and impact on the workforce.” Depending on a lot then.

Real GDP growth forecasts do not reveal what is happening to the inequality of incomes and wealth within the average aggregate. But in its new ‘inclusive economics’ mood, the IMF comments: “the medium-term growth slowdown could affect global income inequality and convergence between countries. A slower growth environment makes it challenging for poorer countries to catch up with those that are richer. Slower GDP growth can also lead to higher inequality, reducing average welfare.” Indeed.

Will inequality widen or narrow in the rest of this decade? The IMF answers: “Depending on the measure analyzed, there is either no or only a modest expected recoupment in the medium term. Small within-country inequality improvements are not sufficient to offset the expected slowdown in between-country inequality convergence.” So the IMF concludes: “The growth slowdown has grim implications for the distribution of income between countries, of global income, or of a more general welfare measure.” It reckons that AI will make inequality worse and “inasmuch as other factors, such as geoeconomic fragmentation, worsen the distribution of income between countries, they will likely worsen global inequality and the distribution of welfare, unless they significantly improve income distribution within countries and other dimensions of welfare, such as life expectancy.”

At the beginning of this decade, just after the pandemic slump hit the world, there was optimistic talk of a repeat of the Roaring Twenties of the 20th century that the US economy supposedly experienced following the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918-19. That designation of the 1920s was always an exaggeration, even in the US; while in Europe there was a serious depression. And the roaring twenties gave way to the Great Depression of the 1930s. But now there is no longer any optimistic talk of a long boom, even if incorporating some possible productivity boost from AI. Now the talk is of the Tepid Twenties – at best.

No comments:

Post a Comment