Greece has a general election today. The conservative New Democracy party under Kyriakos Mitsotakis currently forms the government, having defeated the leftist Syriza party under Alexia Tsipras in the 2019 election. In 2019, New Democracy took 39% of the vote to Syriza’s 32%. When Syriza took power in 2015 at the height of the euro debt crisis, Syriza polled 35% to ND’s 28%. Disillusionment with Syriza among previous strong working-class support was enough for the ND to gain a substantial victory in 2019. The former social democrat party PASOK, which had adopted neo-liberal policies during the debt crisis, polled only 10% and the Communists (who called for leaving the EU) fell to just 5%.

Although voting is formally compulsory, turnout was only 57% in 2019. Indeed, voter turnout has steadily fallen since Greece joined the EU in the early 1980s, but it did rise during the euro debt crisis between 2012 and 2015, which saw Syriza come to power and take on the Troika (the EU, the ECB and the IMF) against their attempt to impose huge austerity measures on the Greek people. Disillusionment with Syriza saw a drop in turnout in 2019.

The latest opinion poll puts ND on 36% and Syriza on 29%, with PASOK on 10% and the Communists on 7%. If that turns out to be accurate then, given that seats are distributed according to the proportion of votes for each party, no one party will get 151 seats in parliament and another election would follow in July. However, in that follow-up election, the leading party will receive a bonus of 50 extra seats (ensuring a ‘super-majority’ in parliament). So it seems likely that ND will be returned to office.

Why is the conservative New Democracy likely to win again? There is no great enthusiasm for either of the main parties and voter turnout is likely to be even lower than in 2019 (even though 17-year olds can vote for the first time). The ND government has lost some support because of its handling of the COVID pandemic; its secret spying (Watergate style) on Pasok’s private communications; and its admission that the terrible recent train crash, which led to the deaths of 57 people, was due to safety regulations being relaxed by the government.

But that will not be enough for the ND to lose for two reasons. First, the ND government is riding on the relative recovery in the Greek economy (even in wages and employment for Greek workers). The Greek economy made one of the strongest recoveries from the Covid-19 pandemic, with real GDP up 8.4% in 2021 and another 5.9% last year. The average annual rate of change of Greece’s GDP has grown 3x during 2019-2022 as compared to the previous period in 2014-2018, from 0.5% to 1.8%. It is now even higher than the EU average rate of 1.3%, growing faster than many other advanced economies in Europe. A similar shift can be seen in GDP per capita.

The amount of loans that are now non-performing on banks’ balance sheets has fallen from more than 50% in 2016 to close to 7%. Total investment in Greece has increased from an average annual rate of 0.7% during 2014-2018 to 7.7% between 2019-2022. At the same time, the EU average fell from 3.6% to 2.2%.

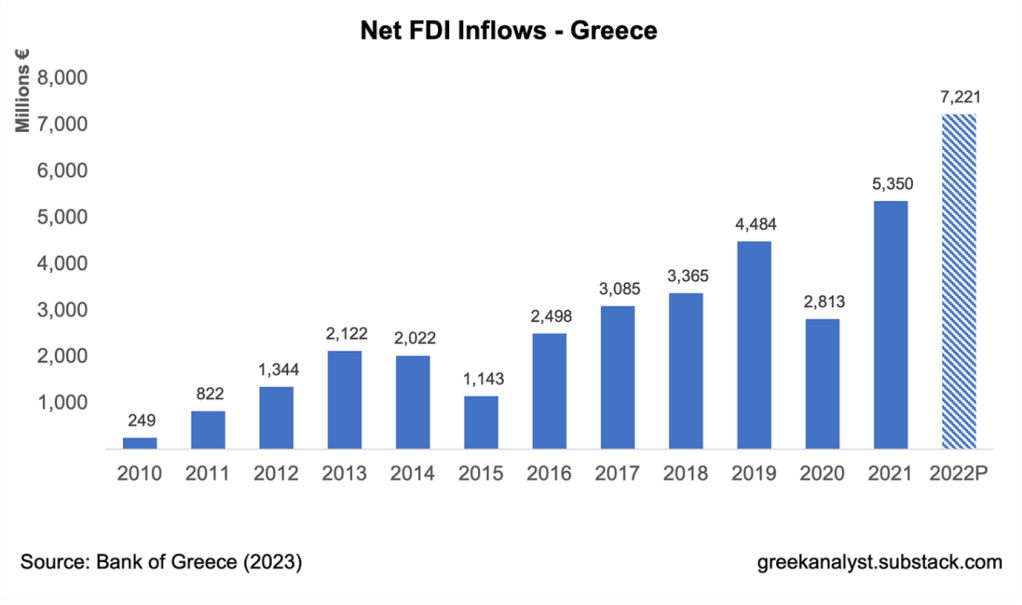

Foreign direct investment rose 50% last year to its highest level since records began in 2002. And the EU’s post-pandemic recovery fund is set to provide €30.5bn of grants and loans to Greece by 2026, equal to 18% of current GDP a long-term boost to the economy.

Tourism — the Greek economy’s largest sector, accounting for about one-fifth of GDP — last year rebounded to reach 97% of pre-pandemic levels. Foreigners are buying up Greek homes like there was no tomorrow (outpricing local Greeks). Unemployment in Greece has been steadily falling, inching closer to the EU average (although youth unemployment is still near 25%).

During the euro debt crisis, half a million Greeks (those educated and better-off) left the country. The ‘brain drain’ is now slowing. But with youth unemployment still nudging 25%, many young Greeks still say that, if they can, they will join the 500,000 who fled overseas during the debt crisis.

The number of companies in Greece has been steadily rising, increasing by almost 38% since 2014. Business activity has been booming.

Investment is up and companies are expanding because the profitability of capital has risen sharply by: cutting wages and jobs; privatisations; and lower corporate taxes.

Source: AMECO, MR calcs

But there is a long way to go to turn Greek capitalism round. While profitability is up, productive investment in Greece remains among the lowest in the advanced capitalist world.

Nevertheless, this relative improvement in the economy is a key reason why the ND is likely to win. But the emphasis is on relative. The recent fast GDP growth since COVID is coming from a really low level of GDP. The Greek economy remains still some 20% smaller than before the Great Recession and euro debt crisis. And the recent investment rise is mostly in unproductive real estate investment.

Finally, a small capitalist economy like Greece, is dependent on what is happening globally. If the major economies enter a slump over the next year, then Greece will not escape. The relative improvement in the economy could be swept away by a new squall in the Aegean and Mitsotakis’ luck will run out. As the OECD puts it in its latest survey, “Greece’s strong recovery is facing mounting external headwinds”. Even without a slump, real GDP growth this year will slow to just 1.3% and reach only 1.8% next year – hardly a boom.

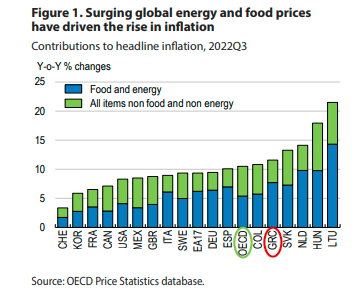

Surging energy prices, supply disruptions and renewed uncertainty, especially since Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, is sharply slowing the recovery.

Also the Troika-set targets on fiscal spending were disrupted by COVID spending, so the new government must apply yet more severe spending cuts to restore those targets.

Above all, this recovery that pleases so much foreign investors, the banks and the corporate sector – and the Troika – has been at the expense of workers’ living standards. Profitability of Greek capital has risen, but Greek workers’ living standards have not. Painful austerity measures have left their mark on a country that now has one of the highest rates of poverty in Europe.

As Syriza leader Tsipras put it: “Greece has Bulgarian wages and British prices.” Real wages have fallen sharply since the debt crisis and the minimum wage is still lower than it was 12 years ago (and the minimum is the base for many wage settlements in Greece). Even Dimitris Malliaropulos, chief economist of the Greek central bank, admitted that Greek capitalism has recovered only by what he called “outright” cuts in wages.

And even though the humungous public debt to GDP ratio, which reached 206% during the pandemic, is now down to 171%, the lowest level since the start of the euro debt crisis, that is still the highest in Europe by some distance – so fiscal austerity will be on the policy agenda for decades ahead. And on nearly every key indicator of public spending that matters, Greece is still way behind.

Only in defence spending is Greece ahead – at 3.5% of GDP, it’s the highest in NATO!

The other main reason that the ND is likely to win is that Syriza disillusioned its working-class support when it capitulated to the Troika in 2015. Back then, in the face of a massive media campaign and threats by the Troika leaders to vote yes to their terms, the Greek people voted 60-40 to reject the austerity measures in a referendum. But immediately afterwards, Syriza ignored the result and agreed to the Troika terms.

I related and discussed the momentous events of 2015 in many posts at the time. I won’t go over the arguments presented then by the mainstream and within the left over what policy to adopt and what mistakes were made. You can read my views here.

But also see this excellent account of the Greek debt crisis by Eric Toussaint. for which I wrote a preface. Syriza’s capitulation to the Troika despite the vote of the Greek people and its implementation of their demands in return for funding ensured victory for the ND in 2019. The legacy of that defeat in 2015 and the revival of Greek capitalism at the expense of Greek workers’ livelihoods since remains a black mark against the Syriza leaders.

No comments:

Post a Comment