Turkey holds a very important general election tomorrow. Incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been in office for more than 20 years. In the election out of an 86m population, there will be over 50m voting with 5.3m new young voters; including Kurds who make up about 18% the population and could be decisive in the result.

For the first time, Erdogan is in danger of losing the election. The latest opinion polls put the opposition alliance slightly ahead of Erdogan’s grouping, but neither side looks like obtaining 50%, necessary to avoid a run-off in two weeks. The election for the parliamentary seats also looks like resulting in neither side having a majority.

The opposition is composed of an alliance of several disparate parties led by Kemal Kilicdaroglu, a retired civil servant, who has vowed to “restore Turkish democracy” and improve ties with the West. Kılıçdaroğlu has led CHP, the secularist party of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Turkey’s founding father, since 2010. At the last minute, the opposition gained a boost when an independent candidate, Muharrem Ince, pulled out of the race, with his support likely to go to the opposition.

Turkey is the 19th largest economy in the world and a member of the G20. During the first decade of Erdogan’s presidency, Turkey’s economy had a degree of expansion, if very much based on a myriad of infrastructure projects and funded by foreign loans. But when people protested over many reckless developments, in particular, in the months-long Gezi park protests in 2013 over a planned urban development in central Istanbul, Erdoğan responded with a violent crackdown.

Erdogan changed the constitution from a parliamentary system to one where the president held most powers. The slide towards authoritarianism gathered pace after a 2016 coup attempt by sections of the military. Erdogan launched a sweeping purge of the security services and the civil service, while imposing a state of emergency that remained in place when elections were held two years later. Since then, he has spent much of the past decade locking up opponents, cowing the media and deposing elected officials and university professors. There are now more journalists in prison than in any other country. Selahattin Demirtaş, the former Kurdish leader, has been in jail for seven years on charges of ‘supporting terrorism’ and Istanbul mayor Imamoğlu from the opposition faces a possible ban from politics after a court convicted him in December of “insulting” electoral officials.

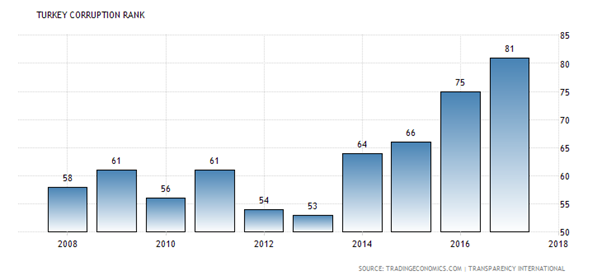

Corruption in the government has increased and Turkey moved further up the corruption ladder under Erdogan.

But since the COVID pandemic slump, things have turned for the worse for Erdogan. His electoral support (based mainly on rural voters with religious beliefs) has dropped – already all the major cities are run by opposition administrations. Now he faces a possible defeat for the presidency. The main reason for his loss of support is the state of the Turkish economy with inflation near 50% a year; economic growth stuttering; the trade deficit widening; the currency diving and foreign debt at record levels.

The economic situation was exacerbated by the horrendous earthquake that devastated southern Turkey in February, killing more than 50,000 people and displacing another 3m. Erdogan’s handling of the disaster has been heavily criticised. At the same time, runaway inflation under Erdoğan’s watch has hurt every household. The price of a kilo of onions, vital for Turkish cuisine, has increased around five-fold in the capital city of Ankara over the past 18 months.

Erdogan has refused to follow orthodox capitalist policies to control inflation, namely to raise interest rates, as most central banks have done globally. Describing interest rates as “the mother and father of all evil”, he has sacked central bank governors if they adopted conventional inflation policy i.e raising rates. But with interest rates kept well below inflation, the lira currency has weakened sharply against the dollar and the euro and so the cost of servicing foreign loans for industry has rocketed.

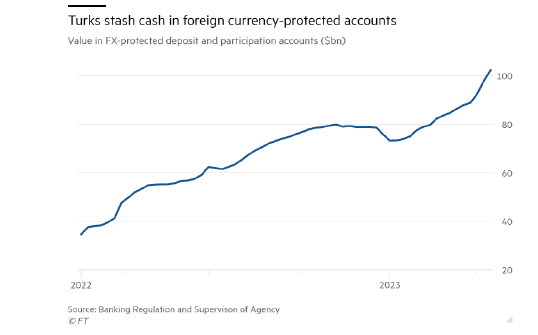

The government introduced special savings accounts in 2021 to reimburse depositors if the lira weakened. These accounts now hold the equivalent of $102bn. So they pose a big liability to the government budget, forcing the central bank to ‘print’ money to fund government spending, further increasing the downward pressure on the lira.

The trade deficit continues to widen sharply as imports paid for in foreign currency have risen. The overall current account deficit relative to GDP has more than doubled during the Erdogan years.

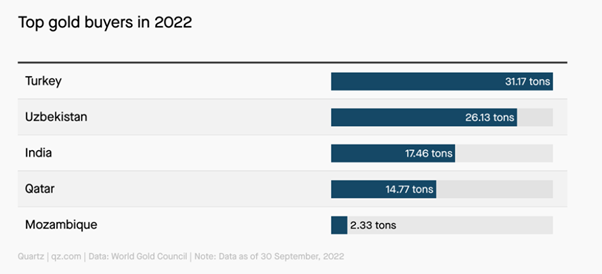

And there has been a massive increase in speculative gold imports (now one-third of all imports) to use instead of lira to make foreign transactions. Erdogan has called people to buy gold to avoid using dollars or euros: “Those who keep dollar or Euro currency under their mattresses should come and turn them into Liras or gold.” These imports come from Russia which is selling gold for its war effort and to evade sanctions.

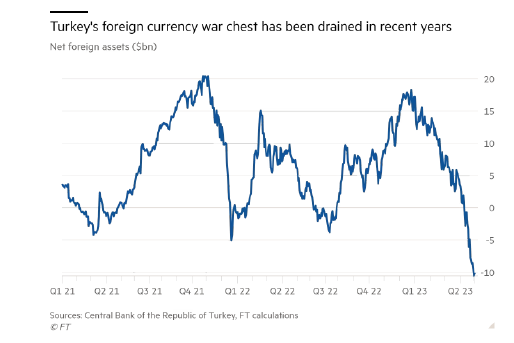

Even so, Turkey has run out of foreign currency to pay its debts, increasingly resorting to swapping agreements (in effect short-term loans) with friendly Gulf nations like the United Arab Emirates, from which Turkey has borrowed Emirati dirhams in exchange for lira. But as the election starts, Turkey’s net foreign currency reserves are down to a negative $67billion.

Foreign investors are avoiding Turkey like the plague. Foreign ownership of Turkish government bonds has fallen from 25% in May 2013 to below 1% in 2023. Similarly, investors have pulled out more than $7 billion from the Turkish stock market. Turkey banks and corporations are now in dire trouble. Turkey’s non-financial companies’ foreign currency liabilities now outstrip their foreign exchange assets by more than $200bn.

What the Turkish economy shows is that trying to run economic and monetary policy in the opposite direction to that of the major advanced capitalist economies cannot work unless capital controls are introduced and domestic investment is directed through a plan towards productive sectors. Instead, Erdogan is trying to have a successful capitalist economy completely exposed to international capital flows and based on credit-fuelled investment in real estate and other unproductive sectors.

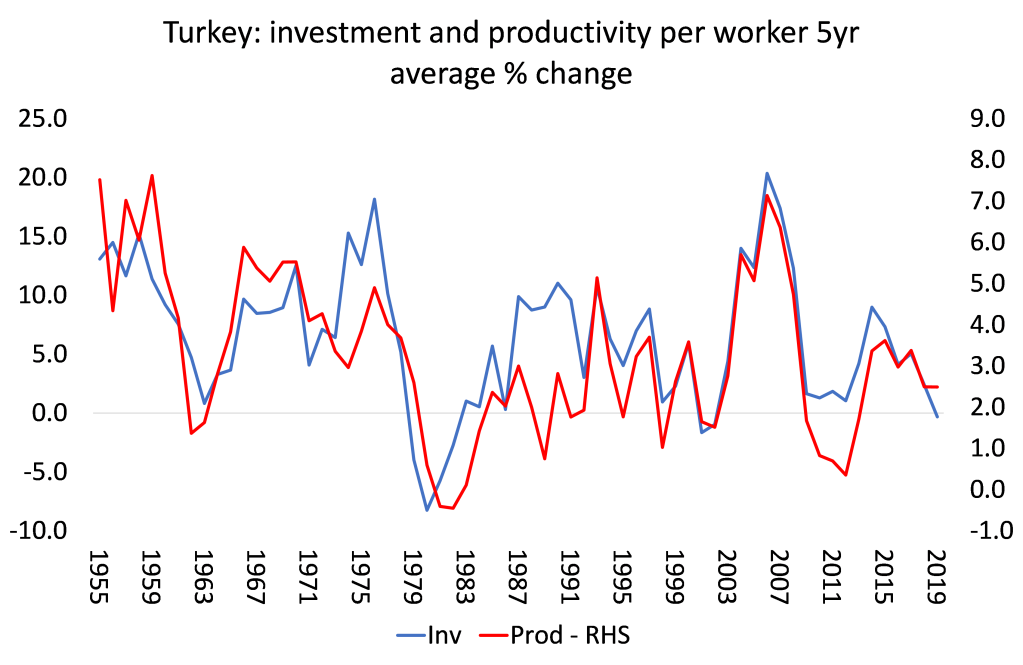

A key measure of economic success is growth in the productivity of labour. That has been heading south. The reason is that investment growth in productive sectors per worker has been slowing fast. In the first decade of Erdogan’s rule, there was double-digit growth in both investment and productivity. But since the end of the Great Recession of 2009, growth in the second decade has been less than 3% a year on average.

And behind this slowing investment and productivity growth is the steep decline in the profitability of Turkish capital since the end of the Great Recession.

Source: Penn World Tables 10.0

If the opposition wins, they are not offering a socialist alternative to Erdogan’s maverick economics. Opposition leader Kılıçdaroğlu told the Financial Times last month that one of his priorities would be establishing an independent central bank so that it could set interest-rate policy without government interference! That would mean a sharp rise in interest rates as conventional policy was adopted and probably more fiscal austerity. Some supporters of the opposition have argued that “interest rates might need to rise to 30% to break inflation. This would maximise foreign investment, boosting economic growth while alleviating the pressure on the lira.” But this assumes that hiking interest rates would work to lower inflation – a recession is more likely to result.

Under Kılıçdaroğlu there would be a swing back towards the European Union and support for NATO in Ukraine. Reviving Turkey-EU relations would be high on the agenda should he win the presidency. Here the policy of the opposition becomes clear: orthodox economic policy and a reliance on foreign capital.

But will foreign capital deliver? Turkey has massive investment needs. The US$50 billion cost of building new homes in regions hit by the two recent earthquakes is just one example. There is deep poverty and inequality. Since the coronavirus pandemic, Turkey’s poverty rate has reached 21.3% of the population, according Turkish Statistical Institute’s annual survey, just released . The severe material deprivation rate — defined as the rate of people unable to afford at least four of key necessaries — is 16.6%. According to the 2022 results, 33.6% of the non-institutional population had heating problems due to isolation and problems in their dwellings such as leaking roof, damp walls/floors/foundation, rot in window frames/floors etc.

According to the survey, Turkey’s gini coefficient, a statistical measure used to gauge economic inequality, worsened by 0.015 points to 0.41 in 2020 — a level comparable to those of Brazil, Mexico and South Africa. It’s the largest gap between rich and poor in eleven years under Erdogan. The ratio of the income of the richest 20% of the population to that of the poorest 20% increased to 8 in 2020 from 7.4 the previous year. The richest 20% received 47.5% of the total income, while the poorest quintile got only about 6%. In terms of deciles, the top 10% of the population received 32.5% of the total income, while the share of the bottom decile was 2.2%, with the ratio increasing to 14.6 from 13 over a year.

The election outcome is not certain. Even if Kılıçdaroğlu were to get 50% of the vote and win in the first round, there is no guarantee that Erdogan would accept the result, just as Trump did not in the US 2020 election. He may find ways to block the result and demand a new vote. That could push the country into a major convulsion. If nobody gets 50%, a second round would take place at the end of May.

No comments:

Post a Comment