by Michael Roberts

Last week, Ghana’s central bank announced its biggest ever

interest-rate hike as it sought to slow rampant inflation that threatens

to create a debt crisis in one of West Africa’s largest economies. The

Bank of Ghana raised its main lending rate by 250 basis points to 17%

as consumer inflation reached 15.7% year-on-year in February, the

highest since 2016. The war in Ukraine will likely make things worse.

Ghana imports nearly a quarter of its wheat from Russia and around 60%

of its iron ore from Ukraine.

Ghana is just one example of the economic stress being placed on small, low-income economies around the world from food and energy inflation, rising interest rates and a strong dollar. The island nation on the south east coast of India, Sri Lanka, has begun talks with the IMF for a ‘debt relief’ package after protests over a deepening economic crisis forced Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s government into a policy U-turn. Sri Lanka has for months faced mounting economic pain as its depleted foreign currency reserves triggered shortages of imports and fuel, power blackouts and double-digit inflation. It has debt and interest repayments worth about $7bn due this year against usable foreign currency reserves as low as $500mn.

Sri Lanka is Asia’s largest high-yield bond issuer, borrowing heavily in the years following the end of its 2009 civil war. It has never defaulted. But it looked set to do so before it turned to the IMF. About one-third of its debts are owed to international bondholders while other large creditors include countries such as China and India. It is expected to finalise a $1bn credit line with India. And even with IMF money, it will probably have to default and ‘restructure’ its debts with creditors.

In doing so, Sri Lanka will join countries such as Suriname, Belize, Zambia and Ecuador that have already defaulted on their debts during the pandemic. Pakistan too is on the brink of default, with its government under Imran Khan forced into calling elections.

Egypt has also asked for support from the IMF, as the country struggles to weather the economic impact of Russia’s invasion on Ukraine. Egypt is the Arab world’s most populous nation and has ‘benefited’ from previous IMF loans and programmes. In 2016 it secured a $12bn loan over three years after a crippling foreign currency crisis as it emerged from the political upheavals that followed its 2011 revolution. It also received $8bn in 2020 to deal with the impact of the pandemic, making it one of the biggest borrowers from the IMF after Argentina. At the time of the 2016 agreement, it devalued the currency, which lost half its value against the dollar. Foreign debt investors have also pulled billions of dollars from Egypt in recent months, adding to pressure on its currency.

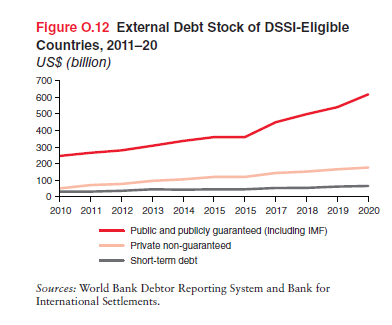

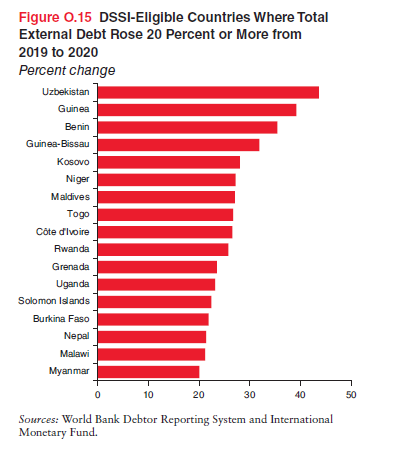

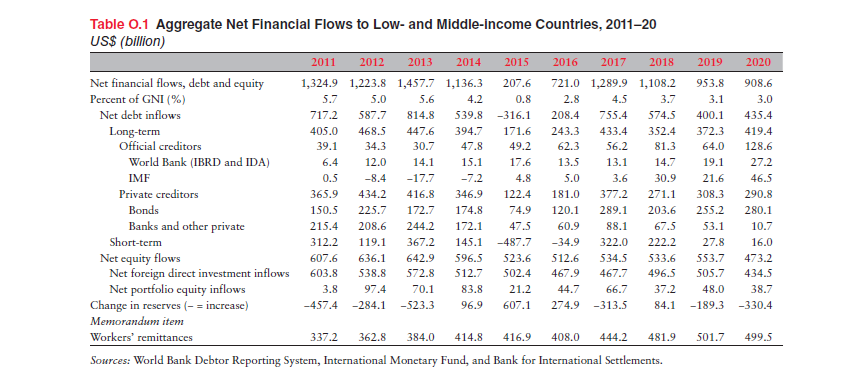

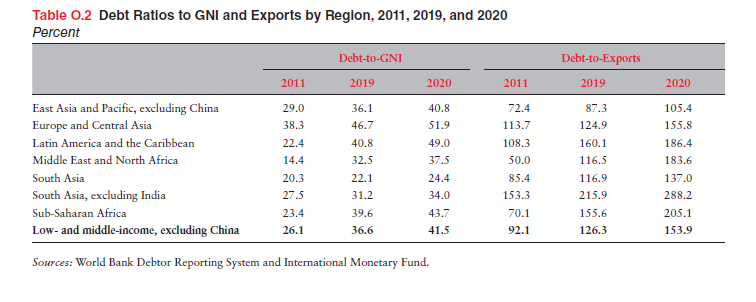

I’ve raised this before, and both the IMF and the World Bank have warned, many countries are emerging from the COVID pandemic slump with a large debt overhang that could crippled their economies if they are forced by creditors, both private and public, to repay. And while many of these countries are small in GDP size, they are huge in population. The IMF’s debt database shows that the external debt stock of low- and middle income countries in 2020 rose, on average, 5.6 percent to $8.7 trillion. However, for many countries the increase was in double digits. The external debt stock of countries eligible for the Group of Twenty (G-20) Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) rose, on average, 12 percent to $860 billion and in some of them by 20 percent or more. And that debt initiative, which just suspends payments on debts for a few years, has now come to an end.

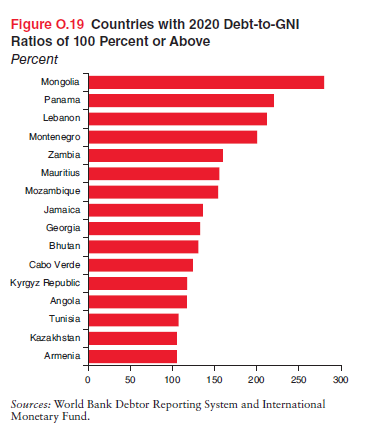

The combined debt service paid by DSSI-eligible countries in 2020 on external public and publicly guaranteed debt, including the IMF, totalled $45.2 billion, of which principal accounted for $31.1 billion and interest for $14.1 billion. The 2020 debt service comprised $26.4 billion (58 percent) paid to official bilateral and multilateral creditors and $18.8 billion (42 percent) to private creditors, that is, bondholders, commercial banks, and other private entities. Many small countries have external debt levels well above 100% of annual GDP.

Prior to the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the impact of the pandemic on low-income countries’ public spending and revenues had produced an increase in their gross sovereign borrowing equivalent to about 25 per cent of their GDP.

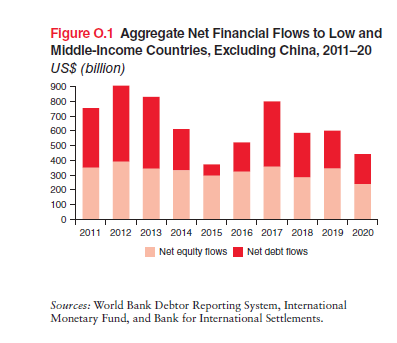

Capital flows to the poorer countries of the world by the imperialist core has been falling since the end of the Great Recession, another indicator of the decline in globalisation. In 2011, $1.3trn went into the ‘Global South’ from the Global North. In 2020, that annual figure had fallen to $900bn, a 30% fall. And remember that over half of all financial flows to the Global South go to China. Excluding China, the fall in capital flows to the poorest countries is even greater. Over the past decade almost 60 percent of net aggregate financial flows to low- and middle-income countries from external creditors and investors went to China. Over this period China received inflows close to $4 trillion, of which 40 percent were debt-creating flows and 60 percent were foreign direct investment and portfolio equity flows. In 2020, aggregate financial flows to China rose 32 percent to $466 billion, driven by a 62 percent increase in net debt inflows to $233 billion and a 12 percent rise in net equity inflows also to $233 billion.

Private creditors (investment funds etc) have cut back on their investment in the government and corporate bonds of the poor countries and international banks have stopped lending. Much of the capital flows into these poor countries was not even for productive investment but merely to cover previous debts or for speculation by foreign investors in local financial markets. Foreign direct investment (FDI) has fallen from $600bn in 2011 (or about 40% of all capital flows) to $434bn in 2020. You might argue that financial investments by foreign multinationals and investment speculators is the last thing these countries need. But if foreign capitalists are reducing their investments, what is to replace it, either for productive investment in these poor economies or just to cover existing debt repayments? The answer is IMF-World Bank money with all sorts of conditions; and increased remittances by those who left their countries and got jobs and incomes working abroad. For all the data – see the table below.

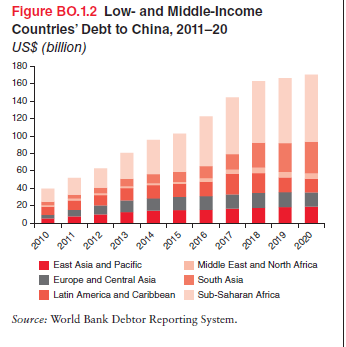

One controversial issue in capital flows to the Global South is the role of China. China has become an important creditor to many poor countries, starved of funds by the ‘West’ and desperate for credit to cover existing debts and to carry out infrastructure and productive projects. Low- and middle-income countries’ combined debt to China was $170 billion at end-2020, more than three times the comparable level in 2011. To put this figure in context, low- and middle-income countries’ combined obligations to the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development were $204 billion at end-2020 and to the International Development Association $177 billion. Most of the debt owed to China relates to large infrastructure projects and operations in the extractive industries. Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, led by Angola, have seen one of the sharpest rises in debt to China although the pace of accumulation has slowed since 2018. The region accounted for 45 percent of end-2020 obligations to China. In South Asia, debt to China has risen, from $4.7 billion in 2011 to $36.3 billion in 2020, and China is now the largest bilateral creditor to the Maldives, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

Some argue that this shows China is just as ‘imperialist’ as the West and that China is putting poor countries into a permanent ‘debt trap’. But the evidence for this is weak. Most Chinese credits are on no worse terms than that offered by the IMF and other bilateral creditors, and in many cases are much better. China is supposed to use ‘debt diplomacy’ against the interests of debtor nations. But debt diplomacy is actually used by the West more, as the examples of Argentina and Ukraine show.

In sum, debts to foreign investors and financial institutions owed by the Global South have accelerated during the COVID pandemic and ‘debt relief’ has been no such thing. Now the Ukraine conflict is increasing the risk of defaults and economic recession for these countries as inflation spirals, interest rates rise and economic growth falls away.

Net transfers of financial resources from developing to developed countries far exceed any compensation by net overseas development aid (ODA) flows to developing countries, which averaged less than $100bn a year In 2012, the last year of recorded data, developing countries received a total of $1.3tn, including all aid, investment, and income from abroad. But that same year some $3.3tn flowed out of them. In other words, developing countries sent $2tn more to the rest of the world than they received. If we look at all years since 1980, these net outflows add up to an eye-popping total of $16.3tn.

What’s the answer? Well, the obvious global one is to cancel the debts owed by all these poor countries. Based on the amount their governments are spending on debt payments which leave the country, the Jubilee Debt Campaign estimates that people in 54 countries are currently living in debt crisis, up from 31 in 2018 and 22 in 2015. As well as the 54 countries in debt crisis, Jubilee Debt Campaign estimates that 14 countries are at risk of a public or private debt crisis, 22 at risk of just a private sector debt crisis, and 21 just a public sector debt crisis.

Then there are national solutions. First, governments need to put in place capital controls to stop the reckless flow of speculative capital that destroys national currencies and provokes financial crises. Capital controls are also needed to stamp out illicit and criminal capital flows. US-based Global Financial Integrity (GFI) calculates that developing countries have lost a total of $13.4tn through unrecorded capital flight since 1980.

Even the IMF has admitted that capital controls should be a weapon available to a national government to protect its financial assets and household savings from asset stripping and rich individual and corporation capital flight. The IMF now says that countries should have “more flexibility to introduce measures that fall within the intersection of two categories of tools: capital flow management measures (CFMs) and macroprudential measures (MPMs)”. And controls could be “applied pre-emptively, even when there is no surge in capital inflows, to the policy toolkit.”

Ultimately, the only way poor countries can reduce their exploitation by multi-nationals and international finance is through state control of their banking and strategic sectors of their economies. That, of course, is anathema to international capital.

No comments:

Post a Comment