by Michael Roberts

Apart from inflation and war, what grips current economic thought is

the apparent failure of what mainstream economics likes to call

‘globalisation’. What mainstream economics means by globalisation is

the expansion of trade and capital flows freely across borders. In

2000, the IMF identified four basic aspects of globalisation: trade and transactions, capital and investment movements, migration and

movement of people, and the dissemination of knowledge. All these

components apparently took off from the early 1980s as part of the

‘neoliberal’ reversal of previous national macro-management policies

adopted by governments in the environment of the Bretton Woods world

economic order (ie US hegemony). Then the call was to break down tariff

barriers, quotas and other trade restrictions and allow the

multi-nationals to trade ‘freely’ and to switch their investments abroad

to cheap labour areas to boost profitability. This would lead to

global expansion and harmonious development of the productive forces and

resources of the world, it was claimed.

There was nothing new in this phenomenon. There have been periods of increased trade and capital export before since capitalism became the dominant mode of production in the major economies by the mid-19th century. In 1848, the authors of the Communist Manifesto noted the increasing level of national inter-dependence brought on by capitalism and predicted the universal character of the modern world society: “The bourgeoisie has through its exploitation of the world market given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country. To the great chagrin of Reactionists, it has drawn from under the feet of industry the national ground on which it stood. All old-established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed…. In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of nations.”

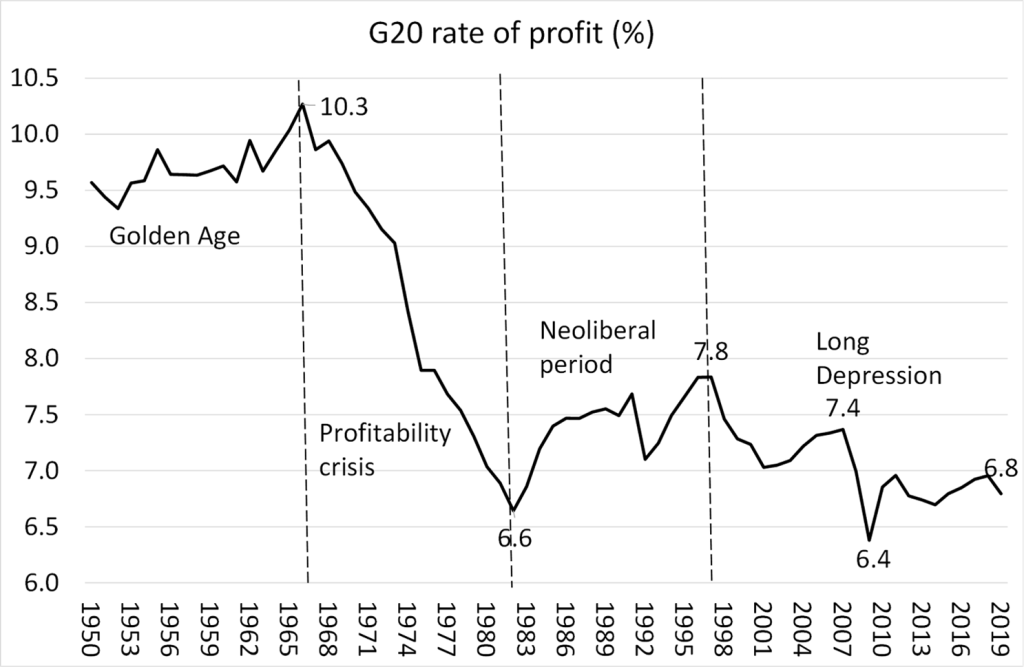

Indeed, we can distinguish previous periods of ‘globalisation’. There was the period of 1850-70 which saw trade and investment expand sharply in Europe and the US (after the civil war), under the auspices of the British hegemony. The depression of the 1870s to 1890s saw the end of that wave. But another wave of global expansion took place in 1890s through to WW1, as new capitalist powers usurped British hegemony. No one power established hegemony and that globalisation wave was stopped in its tracks by world war and continued to reverse through the Great Depression of the 1930s and up to WW2. Then there was a new wave of global expansion under Bretton Woods and US hegemony, before the profitability crisis of the 1970s led to slumps and retraction. From the mid-1980s and through 1990s, there was the largest expansion of trade and cross-border investment in the history of capitalism, with the US and European capitalism spreading its wings further and China entering global manufacturing and trading markets.

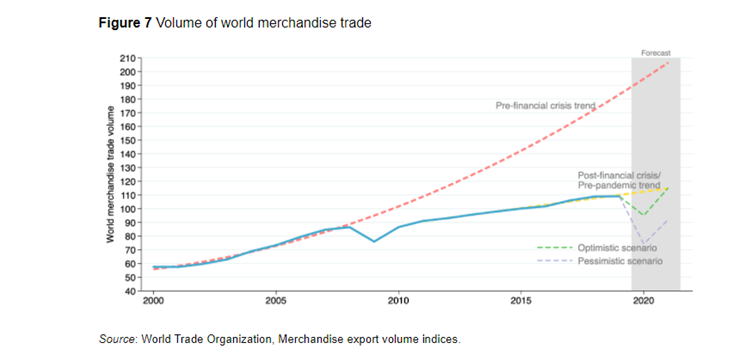

Indeed, according to the World Trade Organisation, a key indicator of ‘globalisation’, the ratio of world exports to world GDP, was broadly flat between 1870 and WW1, fell by nearly 40% in the interwar period; rose 50% from 1950-70; then stagnated until the 1990s, taking off until the Great Recession of 2009; after which, in the Long Depression of the 2010s, the ratio fell by about 12%, a decline not seen since the 1970s.

The latest globalisation wave started to wane as early as the beginning of the 2000s when global profitability slipped back.

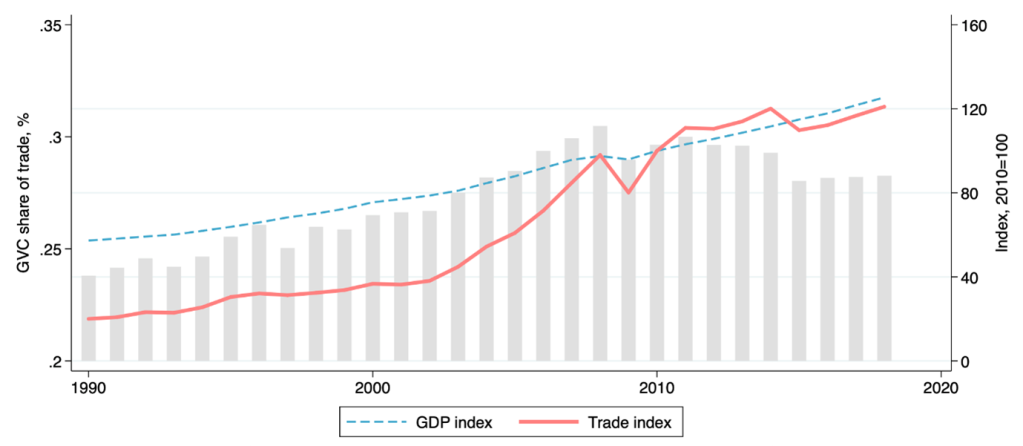

In the 1990s, world trade rose by 6.2% annually, cross-border investment (FDI) by 15.3% a year and GDP globally by 3.8%. But in the long depression of the 2010s, trade rose only 2.7% a year, slower than GDP at 3.1% while FDI rose only 0.8% a year.

Flows of cross-border investment in physical productive assets also stopped growing in the 2010s, while the global ‘value chain’ trade (ie internal multi-national company transfers) also flattened.

Global value chain trade

Of course, Marxist economics could have revealed this outcome of globalisation. David Ricardo’s ‘thought theory’ of comparative advantage has always been demonstrably untrue. Under capitalism, with open markets, more efficient economies will take trade share from the less efficient. So trade and capital imbalances do not tend towards equilibrium and balance over time. On the contrary, countries run huge trade deficits and surpluses for long periods, have recurring currency crises and workers lose jobs to competition from abroad without getting new ones from more competitive sectors (see Carchedi, Frontiers of Political Economy p282). It is not comparative advantage or costs that drive trade gains, but absolute costs (in other words relative profitability). If Chinese labour costs are much lower than American companies’ labour costs, then China will gain market share, even if America has some so-called “comparative advantage” in design or innovation. What really decides is the productivity level and growth in an economy and the cost of labour.

Contrary to the views of the mainstream, capitalism cannot expand in a harmonious and even development across the globe. On the contrary, capitalism is a system ridden with contradictions generated by the law of value and the profit motive. One of those contradictions is the law of uneven development under capitalism – some competing national economies do better than others. And when the going gets tough, the stronger start to eat the weaker. As Marx once said, “capitalists are like hostile brothers who divide among themselves the loot of other people’s labour.” (Theories of Surplus Value Vol 2. p29). Sometimes brothers are fraternal and globalisation expands as in the late 20th century; sometimes they are hostile and globalisation wanes – as in the 21st century.

For Marxist theory, globalisation is really the mainstream word for expanding imperialism. The 20th century started with world capitalism increasingly divided between an imperialist bloc and the rest, with the latter unable (with very few exceptions) to bridge the gap to the top table over the next 100 years. In the 21st century the grip of imperialism remains and if the imperialist economies start to struggle for profitability as they are now, then they start to fight and not cooperate, laying the basis for conflict and division.

Even the mainstream is now aware that free trade and free movement of capital that accelerated globally over the last 30 years has not led to gains for all – contrary to the mainstream economic theory of comparative advantage and competition. Far from globalisation and free trade leading to a rise in incomes for all, under the free movement of capital owned by the trans-nationals and free trade without tariff and restrictions, the big efficient capitals have triumphed at the expense of the weaker and inefficient – and workers in those sectors take the hit. Instead of harmonious and equal development, globalisation has increased inequality of wealth and income, both between nations and also within economies as trans-national corporations move their activities to cheaper labour areas and bring in new technology that requires less labour.

These outcomes are down partly to globalisation by multinational capital taking factories and jobs into what used to be called the Third World; and partly due to neo-liberal policies in the advanced economies (i.e. reducing trade union power and labour rights; casualization of labour and holding down wages; privatisation and a reduction in public services, pensions and social benefits). But it is also down to regular and recurrent collapses or slumps in capitalist production, which led to a loss of household incomes for the majority that can never be restored in any ‘recovery’, particularly since 2009. The capitalist world was never flat even in the late 20th century – and it is certainly mountainous now.

Take tariffs and protectionist measures – the anathema of globalisation theorists. There has been an upward trend in antidumping and countervailing duty investigations in the last ten years (see figure below).

The Great Recession, the weak recovery afterwards in the Long Depression, the COVID pandemic and now the Russia-Ukraine conflict, has blown away global supply chains, stymied global trade and stopped capital movements.

During the 1990s and 2000s, mainstream economics (with few exceptions) lined up with Ricardo and the unblemished merits of globalisation. Just read this piece for the list of the usual suspects (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jul/14/globalisation-the-rise-and-fall-of-an-idea-that-swept-the-world). In the teeth of current trends, some mainstream experts still stick to the view that globalisation will return. “It was inflation that helped create a new policy environment in the mid-19thcentury and in the 1970s. As the economic and political costs of inflation became more obvious and more damaging, it appeared more attractive to look for ways to calm inflationary pressures. For sure, the disinflationary cure — more globalisation as well as more effective government — was temporarily uncomfortable. But it drove the world to seize technical and geographical opportunities once ignored or neglected. There is, in short, a post-conflict future to which we might look forward with some degree of hope.”

One expert claimed that “Finally, call this blind faith, but the last rites for globalisation have been read several times, and on each occasion, it’s bounced up from its sickbed looking quite sprightly. Companies have been resourceful, technology supportive, and even actively destructive governments haven’t crashed it.” Sure, world trade and cross-border investment is not going to disappear and will continue a grow (somewhat) despite pandemics, wars and collapsed supply chains. But that is hardly an argument for saying the previous globalisation wave is not over.

The argument is that the profitability and inflation crisis of the 1970s was followed by the globalisation wave of the 1980s and 1990s. and this could happen again. It’s not a very convincing scenario. The 2020s looks more like the period leading up to WW1, with rival economic powers struggling to gain a chunk of profits (‘hostile brothers’). Writing in the late 1880s, Engels forecast, not harmonious global expansion as German Social-Democrat leader and theorist Karl Kautsky thought, but increased rivalry among competing economic powers resulting in a new European war: “the depredations of the Thirty Years war (of the 17th century) would be compressed into three to four years and extended over the entire continent… with an irretrievable relocation of our artificial system of trade, industry and credit.”, (see my book Engels 200 p129). No return to the global expansion of 1850-70.

The Keynesians seek to return to the days of Bretton Woods with its fixed exchange rates, government fiscal stimulus and gradually reduced tariffs. The Keynesians claim that this would lead to a revival of ‘multilateralism’ and global cooperation. This apparently can restore a world order of peace and harmony. But this is just a denial of history and the reality of the 2020s. The multilateral organisations of the post-war era like the IMF, World Bank and the UN were all under the kind ‘guidance’ of US capitalism. But now US hegemony is no longer secure; but more significant, the high profitability for the major economies post-1945 no longer exists. The brothers are no longer fraternal, but hostile. The current US attempt to maintain its hegemony is more like to trying herd cats into a bag.

It’s perfectly possible to argue that for capital, “Deglobalisation would decrease the efficiency of companies by raising prices and lowering competition and that “with any reversal predicted to slow growth, a deglobalized world would be “vastly inferior” to the past 30 years of open trade.” A recent study by the World Trade Organisation, based on measuring the dynamic impact of lost trade and technology diffusion, found that “a potential decoupling of the global trading system into two blocs – a US-centric and a China-centric bloc – would reduce global welfare in 2040 compared to a baseline by about 5%. Losses would be largest (more than 10%) in low-income regions that benefit most from positive technology spillovers from trade”. Indeed, the collapse of globalisation could turn, not just into a battle between two blocs, but instead into a melange of competing economic units.

But globalisation will only return if and when capitalism gains a new lease of life based on enhanced and sustained profitability. That seems unlikely to happen this side of another slump and maybe more war.

No comments:

Post a Comment