Back in May the Chinese government set up a special zone to implement ‘common prosperity’ in Zhejiang province, which also happens to be the location of the headquarters of several prominent internet corporations– Alibaba among them. And last month, China’s President Xi Jinping announced plans to spread “common prosperity”, heralding a tough crackdown on wealthy elites – including China’s burgeoning group of technology billionaires. At its August meeting, the Central Finance and Economics Committee, chaired by Xi, confirmed that “Common Prosperity” was “an essential requirement of socialism” and should go together with high quality growth.

Over the past fortnight, the tax administration pledged to crack down on tax dodgers and fined Zheng Shuang, one of the country’s most popular actresses, $46m for tax evasion. The Supreme Court declared the 72-hour work weeks common at many private-sector companies to be illegal. And the housing ministry said on Tuesday that it would cap annual residential rent increases at five per cent. And a new layer of officials has been arrested for corruption.

Also, the government is moving to restrict domestic companies from listing on US stock exchanges, in a move threatening to restrict the growth of tech firms that had come to symbolise record Chinese economic growth rates and the emergence of rich company bosses. The years of unbridled speculation by billionaire privately owned companies in league with various local and national officials to do what they want, including usurping state control of the retail banking system, are over.

Billionaires in general, and the mega-wealthy beneficiaries of the tech industry in particular, are now scrambling to appease the party with charitable donations and messages of support. Nasdaq-listed e-commerce website Pinduoduo saiid earlier this year it would donate its second-quarter profit and all future earnings to help with China’s agricultural development until the donations reached at least 10bn yuan ($1.5bn). The move prompted its shares to jump by 22%. Hong Kong-listed Tencent, reading the same signals from Beijing, set aside 50bn yuan for welfare programmes supporting low-income communities, bringing this year’s total philanthropic pledge to $15bn.

The announcement of the ‘common prosperity’ plans was preceded by the arrest of Hangzhou’s (Capital of Zhejiang) top official Communist Party Secretary Zhou Jiangyong by anti-corruption officials. It is rumoured his relatives had been making themselves rich with investments in local internet stocks.

The crackdown on the tech giants and the attempts of the billionaires to gain control of China’s consumer retailing and banking sectors has quickly smashed the hopes of foreign investors too. The Chinese tech sector explosive stock prices have been reversed.

The professed aim of Common Prosperity is to “regulate excessively high incomes” in order to ensure “common prosperity for all”. And it is well known that China has a very high level of inequality of income. Its gini index of income inequality is high by world standards although it has fallen back in recent years.

China: gini inequality of income index (the higher the index, the greater inequality)

The gini inequality measure is used to measure overall inequality in incomes and wealth. In wealth, gini values are much higher than the corresponding values for income inequality or any other standard welfare indicator. China’s inequality of wealth is lower than in Brazil, Russia or India, but still higher than Japan or Italy.

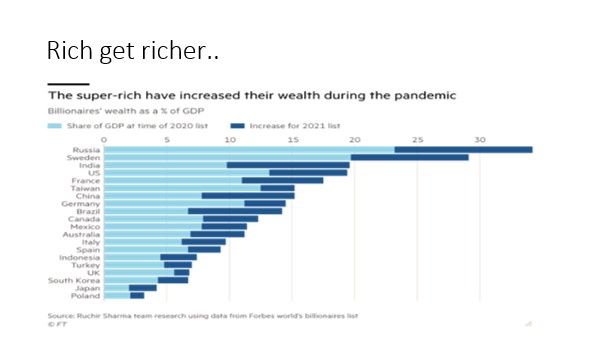

In my view, there are two reasons why Xi and his majority in the CP leadership have launched the ‘common prosperity’ project now. The first is the experience of the COVID pandemic. As in the major capitalist economies, the pandemic has exposed huge inequalities to the general public in China, not just in income but also in rising wealth for the billionaires, who have reaped huge profits during COVID while the majority of Chinese, especially middle-income groups have suffered lockdowns, loss of income and rising living costs. The share of personal wealth for China’s billionaires has doubled from 7% in 2019 to 15% of GDP now.

If this were allowed to continue, it would begin to open up schisms in the CP and the party’s support among the population. Xi wants to avoid another Tiananmen Square protest in 1989 after a huge rise in inequality and inflation under Deng’s ‘social market’ reforms. As Xi put it in a long speech in July to party members: “Realizing common prosperity is more than an economic goal. It is a major political issue that bears on our Party’s governance foundation. We cannot allow the gap between the rich and the poor to continue growing—for the poor to keep getting poorer while the rich continue growing richer. We cannot permit the wealth gap to become an unbridgeable gulf. Of course, common prosperity should be realized in a gradual way that gives full consideration to what is necessary and what is possible and adheres to the laws governing social and economic development. At the same time, however, we cannot afford to just sit around and wait. We must be proactive about narrowing the gaps between regions, between urban and rural areas, and between rich and poor people. We should promote all-around social progress and well-rounded personal development, and advocate social fairness and justice, so that our people enjoy the fruits of development in a fairer way. We should see that people have a stronger sense of fulfilment, happiness, and security and make them feel that common prosperity is not an empty slogan but a concrete fact that they can see and feel for themselves.” My emphases.

As Xi perceptively admitted in this speech about the demise of the Soviet Union: “The Soviet Union was the world’s first socialist country and once enjoyed spectacular success. Ultimately however, it collapsed, mainly because the Communist Party of the Soviet Union became detached from the people and turned into a group of privileged bureaucrats concerned only with protecting their own interests (my emphasis). Even in a modernized country, if a governing party turns its back on the people, it will imperil the fruits of modernization.”

The other reason for Xi’s policy move is that, despite the quick recovery in the Chinese economy from the global pandemic slump, COVID has not been eradicated in China or elsewhere and this has led to a slowing in growth. In August, factory output went into reverse, slumping to an 18-month low, while the main survey of the services sector showed that sector took an even greater hit and contracted for the first time since last March.

Markit business activity indicator (composite) for China – now below 50 (contraction)

Rana Mitter, a historian and director of the University of Oxford China Centre, commented “Party officials fear that the tech giants and the people who run them are out of control and need to be reined in. And then we must add Xi’s determination to be nominated next year for a third term that changes to the constitution now allow.” China’s capitalists imagined that they could act in the same way as those in the G7 economies by investing in property, fintech and consumer media and run up huge debts to do so. But COVID forced the government to try and curb the rise corporate and real estate debt. This has led to bankruptcy of several ‘shadow banking’ concerns and real estate companies. The giant property company Evergrande is struggling to repay $300bn debts and is now expected to go bust, unless the state bails it out. Evergrande claims to employ 200,000 people and indirectly generate 3.8 million jobs in China.

The government had to act to curb the unbridled expansion of unproductive and speculative investment. The latest Financial Stability Report from the People’s Bank of China (central bank) states that between 2017-2019, “the overall macro leverage ratio has stabilized at around 250%, which has won room to increase countercyclical adjustments in response to the epidemic.” In other words, the government could afford the fund the support necessary to get through the COVID slump. But the PBoC admitted that “under the impact of the epidemic in 2020, the nominal GDP growth rate will slow down, the macro hedging will be increased, and the macro leverage ratio will gradually rise. It is expected that it will gradually return to a basically stable track.” So debt is set to rise as China goes into 2022.

The PBoC report claims that it has got all the shadow banking and other risky financial operations under control: “the financial order has been comprehensively cleaned up and rectified. P2P online lending institutions in operation have all ceased operations, illegal fund-raising, cross-border gambling, and underground banks and other illegal financial activities have been effectively curbed, private equity funds, financial asset trading venues and other risk resolution have made positive progress, and the supervision of large financial technology companies has been strengthened.”

But the report is also revealed that there is a section of CP leaders who do actually want to press on with opening up China’s state-controlled financial system to capital (including foreign capital) – and these views are strong within the Western educated bankers in the PBoC. The PBoC report says that it wants to “continue to deepen reform and opening up, further promote the market-oriented reform of interest rates and exchange rates, steadily advance the reform of the capital market, and promote the high-quality development of the bond market. On the premise of effectively preventing risks, continue to expand high-level financial opening.” Apparently, the PBoC officials reckon even more relaxation of the financial regulations will reduce risk!

On the other hand, Xi and his supporters want to control the ‘wild east’ antics of the finance sectors in Shangahi and Shenhzen. Xi is now proposing setting up a new stock exchange in Beijing to lure domestic companies into listing at home instead of overseas. This is part of the strategy to reduce reliance on foreign investment.

According to China ‘experts’ in the West, this crackdown on finance, property and private tech is suicidal to China’s growth. These experts reckon that China cannot sustain its previous growth miracle based on state ownership, planning and investment and instead must let the markets dominate economic policy and investment. The World Bank has been a leader in promoting this strategy for China for decades. The then-World Bank President Robert Zoellick told a press conference in Beijing. “As China’s leaders know, the country’s current growth model is unsustainable.” The so-called middle-income trap describes how economies tend to stall and stagnate at a certain level of development, once wages have risen and productivity growth becomes harder. In early 2012, the World Bank and the Development Research Center, a think tank under China’s State Council, released a 473-page report that spelled out the reforms the country would need to undertake to avoid the “middle-income trap” and ascend to the ranks of high-income nations: ie let market forces rip.

Investment banker, George Magnus, a supposed China expert, has long argued the old chestnut that “at higher income levels, economies become too complex for command-and-control management by individuals. Systems are increasingly what matters. Rules that are transparent, predictable and fairly applied enable market forces to take over the job of directing economic activity, raising efficiency and allowing innovation to flourish.” Magnus, who devoted a chapter to the middle-income trap in his 2018 book Red Flags: Why Xi’s China is in Jeopardy, argues that in pursuing these policies and strategies, “China’s government will stifle incentives and innovation, and make it even more difficult to generate the productivity growth that all high-middle-income countries need to avoid the middle income trap.”

I have dealt with all these arguments in previous posts, so I won’t go into detail again. But the reality is that China is already on the cusp of gaining high-income status, as defined by the World Bank. Based on the World Bank’s current threshold and International Monetary Fund forecasts, the country should achieve that goal before 2025. Indeed, as Arthur Kroeber, head of research at Gavekal Dragonomics in China, has put it: “Is China fading? In a word, no. China’s economy is in good shape, and policymakers are exploiting this strength to tackle structural issues such as financial leverage, internet regulation and their desire to make technology the main driver of investment.” Kroeber echoes my view that: “On a two-year average basis, China is growing at about 5 per cent, while the US is well under 1 per cent. By the end of 2021 the US should be back around its pre-pandemic trend of 2.5 per cent annual growth. Over the next several years, China will probably keep growing at nearly twice the US rate.”

According to a recent report by Goldman Sachs, China’s digital economy is already large, accounting for almost 40% of GDP and fast growing, contributing more than 60% of GDP growth in recent years. “And there is ample room for China to further digitalize its traditional sectors”. China’s IT share of GDP climbed from 2.1% in 2011Q1 to 3.8% in 2021Q1. Although China still lags the US, Europe, Japan and South Korea in its IT share of GDP, the gap has been narrowing over time. No wonder, the US and other capitalist powers are intensifying their efforts to contain China’s technological expansion.

In a report, the New York Fed admits that if China keeps up this pace of expansion, it “is well on track to high-income status… After all, per capita income growth has averaged 6.2 percent over the last five years, implying a doubling roughly every eleven years, and per capita income is already close to 30 percent of the U.S. level.” But the NY Fed argues it won’t be able to as the working population is declining and there will be an insufficient rise in the productivity of labour to compensate. I challenged that forecast in a previous post.

The reason that the NY Fed as well as many Keynesian and other critics of the Chinese ‘miracle’ are so sceptical is that they are seeped in a different economic model for growth. They are convinced that China can only be ‘successful’ (like the economies of the G7!) if its economy depends on profitable investment by privately-owned companies in a ‘free market’. And yet the evidence of the last 40 and even 70 years is that a state-led, planning economic model that is China’s has been way more successful than its ‘market economy’ peers such as India, Brazil or Russia.

As Xi said in his speech: “China is now the world’s second largest economy, the largest industrial nation, the largest trader of goods, and the largest holder of foreign exchange reserves. China’s GDP has exceeded RMB100 trillion yuan and stands at over US$10,000 in per capita terms. Permanent urban residents account for over 60% of the population, and the middle-income group has grown to over 400 million. Particularly noteworthy are our historic achievements of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects and eliminating absolute poverty—a problem which has plagued our nation for thousands of years.”

In contrast, the lessons of the global financial crash and the Great Recession of 2009, the ensuing long depression to 2019 and the economic impact of the pandemic slump are that introducing more capitalist production for profit will not sustain economic growth and certainly not deliver ‘common prosperity’.

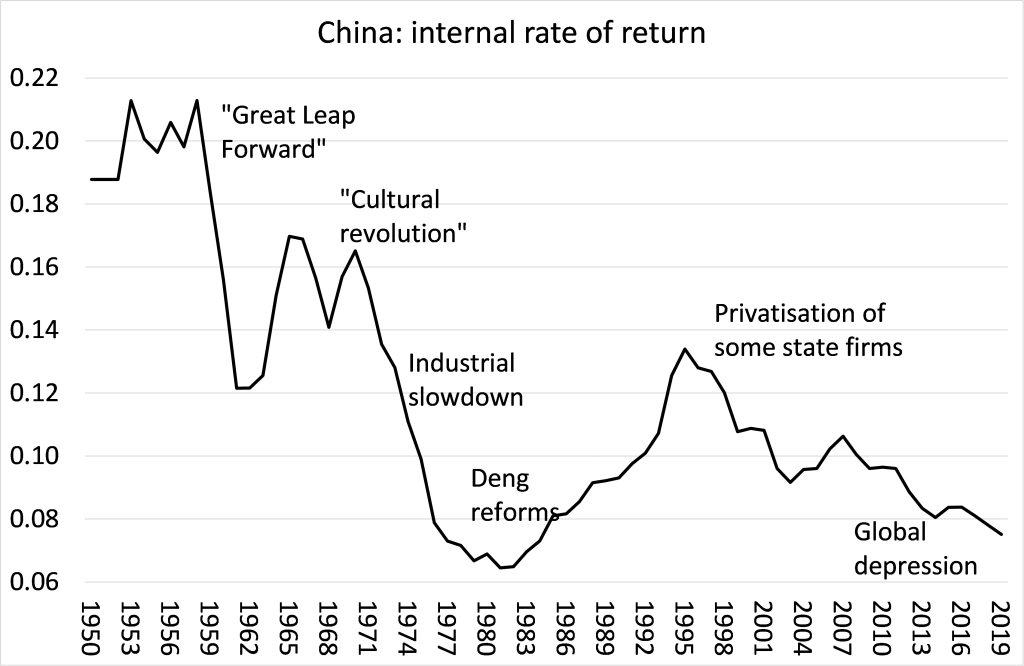

Indeed, it is the capitalist sector in China that is in trouble and threatens China’s future prosperity. China’s capitalist sector is suffering (as it is in the major capitalist economies). Profitability has fallen, reducing the ability or willingness of China’s capitalists to invest productively. That is why speculation in unproductive investment has become ‘uncontrolled’ in China too. Far from the need to reduce the role of the state, China’s future growth through a rise in productivity of labour as the total workforce shrinks in size will depend on state-led investment in technology, skilled labour and ‘common prosperity’.

Source: Penn World Tables 10.1 IRR series

Xi’s crackdown on the billionaires and his call for reduced inequality is yet another zig in the zig-zag policy direction of the Chinese bureaucratic elite: from the early years of rigid state planning to Deng’s ‘market’ reforms in the 1980s; to the privatisation of some state companies in 1990s; to the return to firmer state control of the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy after the global slump in 2009; then the loosening of speculative credit after that; and now a new crackdown on the capitalist sector to achieve ‘common prosperity”.

These zig zags are wasteful and inefficient. They happen because China’s leadership is not accountable to its working people; there are no organs of worker democracy. There is no democratic planning. Only the 100 million CP members have a say in China’s economic future, and that is really only among the top. The other reason for the zig zags is that China is surrounded by imperialism and its allies both economically and militarily. Capitalism remains the dominant mode of production outside China, if not inside. ‘Common prosperity’ cannot be achieved properly while the forces of capital remain inside and outside China.

No comments:

Post a Comment