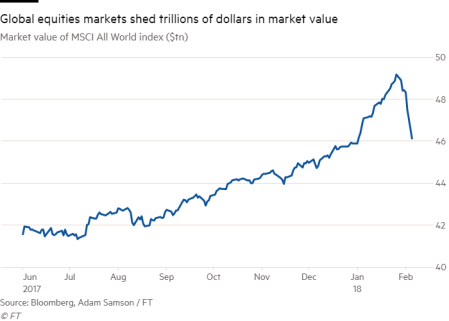

Yesterday, the US stock market fell by the most in one day since mid-2007, just before the credit crunch, the banking crash and the start of the Great Recession.

Is history set to repeat itself? Well, the old saying goes that history never repeats itself but it rhymes. In other words, there are echoes of the past in the present. But what are the echoes this time. There are three possibilities.

This crash will be similar to that 1987 and be followed by a quick and decisive recovery and the stock market and the US economy will resume its recent march upward. The crash will be seen as blip in the recovery from the Long Depression of the last ten years.

Or this could be like 2007. Then the stock market crash heralded the beginning of the mightiest collapse in global capitalist production since the 1930s and biggest collapse in the financial sector ever – to be followed by the weakest economic recovery since 1945.

Or finally it could be like 1937, when the stock market fell back as the US Fed hiked interest rates and the ‘New Deal’ Roosevelt administration stopped spending to boost the economy. The Great Depression resumed and was only ended with the arms race and the entry of the US into the world war in 1941.

Now I have discussed the relationship between the stock market (fictitious capital as Marx called it) and the ‘real’ economy of productive capital in posts before.

On the day of the crash, a new Fed Chair Jerome Powell was sworn in to replace Janet Yellen. Powell now faces some new dilemmas.

Marx made the key observation that what drives stock market prices is the difference between interest rates and the overall rate of profit. What has kept stock market prices rising has been the very low level of long-term interest rates, deliberately engendered by central banks like the Federal Reserve around the world, with zero short-term rates and quantitative easing (buying financial assets with credit injections). The gap between returns on investing in the stock market and the cost of borrowing to do it has been huge.

Of course, every day, investors make ‘irrational’ decisions but, over time and, in the aggregate, investor decisions to buy or to sell stocks or bonds will be based on the return they have received (in interest or dividends) and the prices of bonds and stocks will move accordingly. And those returns ultimately depend on the difference between the profitability of capital invested in the economy and the costs of providing finance. If stock prices get way out of line with the profitability of capital in an economy, then eventually they will fall back. The further out of line they are, the bigger the eventual fall.

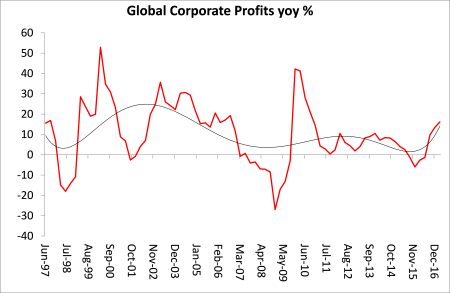

So there are two factors that are key to judging whether this stock crash is a 1987, 2007 or 1937 situation: the profitability of productive capital (is it going up or down?); and the level of debt held by industry (will it become too expensive to service?).

In 1987, the profitability of capital was on the rise. It was right in the middle of the neo-liberal period of rising exploitation of labour, globalisation and new tech developments, all of which were counteracting factors at play against the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. Profitability continued to rise right up to 1997. And interest rates, far being hiked by the Fed, were being reduced as inflation fell.

In 2007, profitability was falling (it had been declining since the end of 2005), the housing market was beginning to dive and inflation was expected to rise and along with it, the Fed planned to raise its policy rate, as it is planning now in 2018. But there are differences from 2007 now. The banking system is not so stretched and engaged in risky financial derivatives. And while profitability in most major economies is still below the peak of 2007, total profits are currently rising. It may be that wages are beginning to pick up and this could squeeze profits down the road. Also, the Fed plans to raise interest rates and thus also squeeze profits as debt servicing costs rise.

Perhaps 1937 is much closer to where US capitalism is now. I have written on the parallels with 1937 before. Profitability in 1937 had recovered from the depths of 1932 but was still well below the peak of 1926.

And more worrying now is that corporate debt since the end of the Great Recession in 2009 has not been reduced. On the contrary, it has never been higher. Based on a global sample of 13,000 entities, the S&P agency estimates that the proportion of highly leveraged corporates — those whose debt-to-earnings exceed 5x — stood at 37 percent in 2017, compared to 32 percent in 2007 before the global financial crisis. Over 2011-2017, global non-financial corporate debt grew by 15 percentage points to 96 percent of GDP.

The stock market crash tells me two things. First, that it is the US economy, still the largest and most important capitalist economy, leads. It’s not Europe, not Japan, not China that will trigger a new global slump, but the US. Second, this time any slump will not be triggered by a housing bust or a banking crash, but by a crunch in the non-financial corporate sector. Bankruptcies and defaults will appear as weaker capitalist companies find it difficult to meet their debt burdens and produce a chain reaction.

But history does not repeat but rhymes. The mass of profits in the major economies is still rising and interest rates, inflation and wage rises are still low relative to history. That should ameliorate the collapse in the prices of fictitious capital (and they are still high). But the direction of profits, interest rates and inflation could soon change.

No comments:

Post a Comment