The recent signing of the TransPacificPartnership (TPP) will benefit American imperialism considerably. But the media has latched onto TPP as the saving grace for Japanese prime minister Abe’s ‘Abenomics’, which has so dismally failed up to now in getting the Japanese economy going. In return for opening-up Japan’s highly protected rice producing and agriculture sector to competition, Japanese industry will see tariffs and other restrictions on its manufacturing exports and investments in Asia and the US reduced.

But I doubt that this will be enough to save Abenomics and an economy that is heading yet again back into stagnation at best, or a slump at worst. Abenomics is supposed to have three arrows: monetary easing; fiscal stimulation and ‘structural reforms’. The first meant that the Bank of Japan would print money like there was no tomorrow and buy up all the government and corporate bonds held by the banks and pension funds, loading them with cash to lend on to businesses to invest and households to spend. This would take the economy out of its deflationary stagnation into an inflationary boom. This was the cry of many Keynesians like Paul Krugman.

Well, the printing presses have certainly worked overtime and the Bank of Japan has expanded its assets to 75% of GDP and still rising, more than double that of Bernanke’s Fed QE program. But it has not delivered. Inflation has not returned and the 2% target looks further away than ever. Even Janet Yellen, US Federal Reserve chair, implicitly criticised the BoJ’s policy, noting in a speech: “I am somewhat sceptical about the actual effectiveness of any monetary policy that relies primarily on the central bank’s theoretical ability to influence the public’s inflation expectations.”

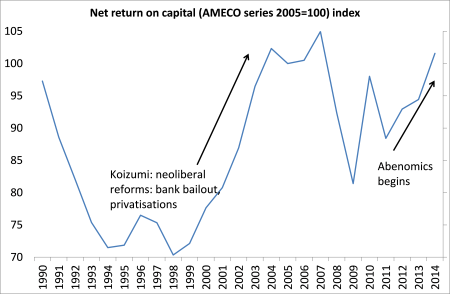

The second arrow was fiscal stimulation i.e. government spending and tax reductions. Well, government spending was curtailed because of worries about a rising public sector debt level of around 250% of GDP, way above anywhere else in the world. Taxes for corporations were sharply cut, but the sales tax on goods purchased by households was sharply increased. This did two things: Japanese capital saw a significant rise in profits and Japanese people saw a sharp drop in real wages and consumption dropped back.

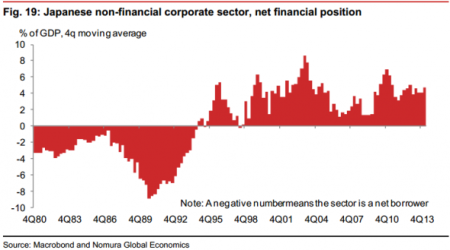

And here’s the rub. Although Japan’s big companies are now rolling in profits, they are not investing in new technology or plant. Japanese corporate profits have soared about 50 per cent since Abe took power and are now significantly above the 2008 peak.

But Japanese corporations are holding onto their cash.

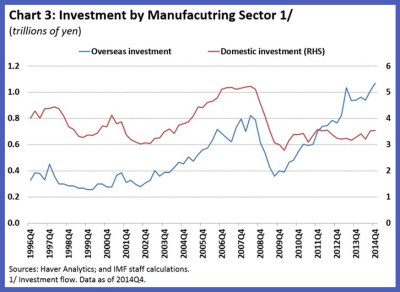

or investing it abroad or buying financial assets.

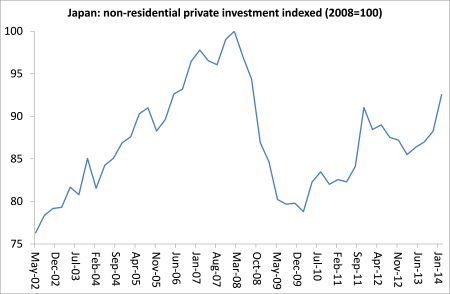

A rebound in capital expenditure in Japan has proved elusive, with machine orders slumping at their fastest pace in 10 months. Machine orders – a proxy for private capital expenditures – fell 3.5 per cent in August from a year earlier. It was the biggest drop since a 14.6 per cent fall in November 2014. So consumption is weak and investment is poor. And unemployment is persistently higher than the 1970-90 average.

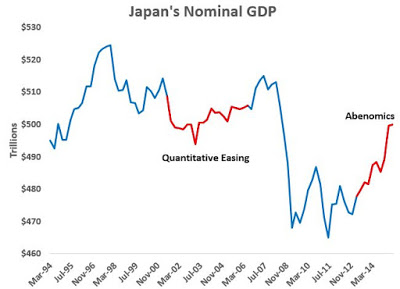

Abenomics has failed. Japan is now on the verge of a ‘technical recession’ – two consecutive quarters of contraction in GDP. Industrial production for August — a crucial input into gross domestic product — unexpectedly fell by 0.5 per cent on the previous month after a 0.6 per cent fall in July. An overall contraction for the third quarter is almost certain, prompting a number of economists to predict a fall in GDP. This would be a second Japanese recession in the space of two years – a double-dip.

Now Abe is trying again with a new policy of targeting nominal not real GDP growth. So this would mean aiming to raise inflation just as much as real growth. Abe says his government will aim at 20% rise in nominal GDP (ie before inflation) by 2020. This is actually a very modest aim, in effect under 4% nominal growth (2% inflation and 2% real GDP?) a year.

But this target is something that Abenomics-1 failed to achieve and there is nothing in Abenomics-2 to suggest that it will succeed. Real GDP growth comes from rising employment plus rising productivity per employed worker. With employment flat or falling and productivity growth less than 1% a year, then to meet the new target, inflation would have to rise to over 3% a year. Under Abenomics-1, real GDP has averaged 0.58% year-on-year growth every quarter since 2013:Q1 and inflation has averaged 0.93% growth.

Keynesians like Paul Krugman now appear to recognise the failure of monetary easing under Abenomics and instead now advocate a big fiscal stimulus even if it sends government debt to GDP ratios up further. Now the Keynesians argue that we need to convince the Japanese that these debts will never be paid and then they will start to spend as they expect a sharp rise in inflation, which is what is needed! This tortuous logic is the sum total of the Keynesian answer to Japan’s stagnation.

The Keynesians and Abe do not address the real issue: why is Japanese corporate investment so sluggish despite high profits. It’s true that the profitability of Japanese firms has improved. And that was the real agenda behind Abenomics. Abenomics did that by squeezing the living standards of Japanese households. This was the outcome of Keynesian-style policies!

However, the recovery in corporate investment remains subdued, in particular for large firms whose investment has been largely flat over the last few years. Considering how closely corporate investment shadowed profitability during previous cycles, the recent slow recovery in corporate investment is exceptional. Business investment is still below the pre-global crash peak and not much higher than in 2012.

One notable feature of Japanese firms over the past decades has been the increase in offshore production, briefly interrupted by the global financial crisis. Over the last two decades, Japanese firms have expanded abroad to exploit cheaper labour, and rising demand in host countries. Overseas investment grew at a rate of 7 percent in the mid-1990s and 12 percent in the mid-2000s before the global financial crisis. The IMF finds that for large firms, in particular those which have expanded production abroad, domestic profitability is less important as a factor driving their investment.

Japanese capital increasingly looks to invest overseas where it expects higher profitability. Thus the economic growth, employment and incomes for Japanese labour remains in the doldrums. And recession approaches again.

No comments:

Post a Comment