So the Greek parliament has approved the terms of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Euro credit institutions for a third bailout deal valued at €86bn over three years (Greece MOU). The terms of the bailout funding commit the Greek government to a new round of austerity measures, including pension cuts, tax increases, a ‘fire sale’ of state assets, a reduction in labour rights and an end to minimum wage rises and a reversal of public sector re-employment.

No wonder about 32 Syriza MPs voted no to the deal and another 11 abstained. That means that the Tsipras government would not command a majority in parliament in any confidence vote if that rebellion was repeated. Tsipras plans an emergency Syriza conference in September and then will probably call a general election for the autumn. That adds a new political uncertainty to the implementation of this deal.

But that is not the only uncertainty. The economic uncertainty is whether, even if the Greeks follow the deal to the letter, it will work to reduce Greece’s public sector debt burden, restore economic growth and reduce unemployment and reverse the drastic fall in living standards. The answer to that question is clear. It won’t.

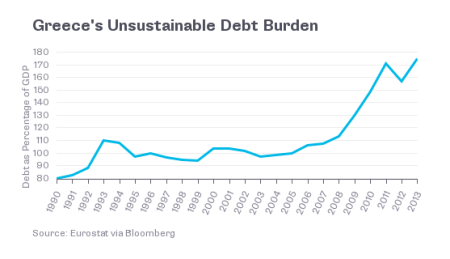

The IMF is not prepared to provide any further credit as part of this bailout because it does not think that Greek public sector debt can be stopped from rising as a share of GDP and that the Greeks can ever service it by borrowing from the market. In other words, the debt is ‘unsustainable’. And in its latest analysis, the EU Commission experts also agree with the IMF.

Here is the summary statement from the IMF released just today on the Greece’s public sector debt sustainability: “Greece’s public debt has become highly unsustainable. This is due to the easing of policies during the last year, with the recent deterioration in the domestic macroeconomic and financial environment because of the closure of the banking system adding significantly to the adverse dynamics. The financing need through end-2018 is now estimated at Euro 85 billion and debt is expected to peak at close to 200 percent of GDP in the next two years, provided that there is an early agreement on a program. Greece’s debt can now only be made sustainable through debt relief measures that go far beyond what Europe has been willing to consider so far.” That could not be clearer (IMF on Greek debt).

So the Greeks are being subject to further severe austerity in trying to run surpluses on the government account (before interest payments) rising to 3.5% of GDP by 2018 – to no avail. Indeed, the IMF says in its statement that “Greece is expected to maintain primary surpluses for the next several decades of 3.5 percent of GDP. Few countries have managed to do so”, Yes, the IMF says, it is decades of austerity!

Both the IMF and the EU Commission reckon that the Greek government debt ratio, currently around 180% of GDP, will probably rise to over 200% of GDP before there is any sign of a fall and will anyway stay well above any level that is considered ‘sustainable’. So the whole thing is a waste of time and pain. No wonder German finance minister Schauble wants to forget it and let Greece take a ‘holiday’ (for at least five years) from the euro – see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/07/26/grexit-de-long-and-the-wages-of-sinn/.

Of course, this partly depends on what is considered ‘sustainable’. As I have shown in previous posts, the interest to be paid on the current Greek public debt is quite low, just 2% of GDP. So if the Greek economy grows by an average of 2% a year over the next three years, and assuming that the government balances its books from now on, then the annual debt servicing costs can be covered without any rise in debt to GDP,

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/07/19/the-euro-train-going-off-the-rails/.

But that is a big ‘if’. It’s true that the Greek economy actually grew 1.4% yoy in Q2 2105, but that was before the impact of the closure of the banking system in July and the squeeze on credit for businesses. The IMF reckons that the debt bailout programme agreed also assumes that the Greek economy will “go from the lowest to among the highest productivity growth and labor force participation rates in the euro area”. How likely is that given the austerity measures? Even the so-called labour reforms planned (trade union rights, cuts in public sector employment, pension rights etc) won’t deliver. Indeed, as I have pointed out before, IMF researchers have found no evidence that such neo-liberal labour reforms deliver any improvement in growth

(http://touchstoneblog.org.uk/2015/04/labour-market-deregulation-when-the-facts-change/

and Box 3.5 in

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/01/pdf/c3.pdf).

And yet, both the Euro institutions and the IMF insist on these measures. Of course, these labour ‘reforms’ are not really about improving efficiency and productivity, but more about squeezing labour and boosting profit share.

The other escape clause for Greek debt could be if Eurozone economic growth were to accelerate and thus revive the Greek economy, as a rising tide lifts all boats. But the signs of regional growth much above 1% a year are not good. The latest Q2 data out today showed both Germany, France, Italy and the Netherlands slowing, so that Eurozone GDP expanded only 0.3%.

And anyway, the Eurogroup and its credit institutions, as well as the IMF, want the debt ratio to fall and for their previous loans to be paid back. The target for 2030 is a 60% of GDP limit for all Eurozone members. But even if Greek governments apply austerity right through to then, the Greek public debt to GDP will still be above 100%.

Moreover, there is no way the Greeks can ‘return to the market’ to raise money to repay the IMF and the Euro institutions at a 2% interest rate. The market will charge at least 6%, according to the IMF, and that is impossible for the Greeks to pay. So this ‘bailout’ would have to be followed by another and another, as far as the Greek and German eyes can see.

That is why there is all this talk of ‘debt relief’. This could mean actually cutting the debt outstanding in cash terms, similar to the deal that Germany got in 1953, in ‘writing off’ the debt it owed to the Allied Powers after the second world war. That was done to allow Germany to return to the capitalist fold and allow economic recovery. But no such ‘haircut’ is being considered for Greece. The German leaders do not want to tell their electors that Germany must accept a haircut on its portion of the loans to Greece. The IMF has proposed a 30% haircut but that would only get the debt down to 120% of GDP – and the IMF and the ECB will not consider any haircut on their outstanding loans.

The other option is to reduce further the interest charged on the loans and extend the period of repayment and the maturity of the loans even further. Already, the existing Euro institution loans do not start to be paid back until 2022. One proposal is that the old loans and the new bailout loans repayments be pushed back for 30 years or even longer. In effect, to use the economic jargon, this would lower the ‘net present value’ of the debt to such a low level that Greece could fund the debt costs each year ‘sustainably’. The debt would ‘perpetually’ rolled over. The Euro institutions would get their interest but never be repaid any of the principal in successive bailouts.

Such a solution remains on the table and will depend, it seems on the Greek government, whatever its complexion in the autumn, keeping to the terms and schedule of the MoU, as reviewed by the ECB, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Commission and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the newcomer making it a ‘quadriga’, not a Troika any longer. This is Greece’s third macro-economic adjustment programme in five years, after the first in 2010 and second in 2011. It looks just as likely to fail as the last two in restoring Greek ‘debt sustainability’, let alone economic growth, employment and living standards.

What is the alternative? I outlined some options in my July post: https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/07/05/no-but-what-now/.

No comments:

Post a Comment