It looks as though the negotiations between the Greek Syriza government and the Eurozone leaders will go right to the wire. It won’t be clear whether there will be a deal or not until Monday 16 February, when the Eurogroup of finance ministers meet again.

Amid the flurry of comments, opinions and rumours, it seems that we can discern some red lines of no retreat for both sides. For the Greeks, PM Tsipras has made it clear that there can be no continuance of the Troika programme and no further austerity measures. There must be some ‘fiscal space’ for the Greek government to spend on the ‘humanitarian crisis’. For the Eurozone leaders, led by the Germans, the red line is that there will be no more money or better terms unless Greece stays in a Troika or EU programme that can be monitored by the creditors i.e. EU governments, the IMF and the ECB. This looks like an impasse, but we shall see.

While we wait to see if there is a deal, let’s consider the wider picture. This crisis shows that the whole euro project is a botched form of currency and fiscal union, one that has taken this form because of the ambitions of German and French imperialism on the world stage.

What the period of Greek membership of the Eurozone has shown is that Greek capitalism has failed. Indeed, so has capitalism in all the smaller Eurozone nations. Nothing demonstrates more the need for a pan-European economy to use all the resources of the continent, both material and human. The smaller and weaker capitalist economies have been driven into a long winter of depression by the global slump. The euro crisis is not really one of sovereign debt or a fiscal crisis. Its origin lies in the failure of capitalism, the huge banking and private credit crisis and the inability of undemocratic pan-European capitalist institutions like the European Commission, the ECB, the Council of Ministers and the pathetic European parliament to deal with it.

The ambition of France and Germany to compete with the US and Asia on the world stage through monetary union was fundamentally flawed. The original dream of a united capitalist Europe, of free markets in production, labour and finance, ever utopian, has turned into a mess. Now the single currency union is under threat. It always was ambitious.

The American investment bank, JP Morgan, recently looked at whether the ‘right conditions’ under capitalism existed for setting up a currency union in Europe. They measured the difference between countries using data from the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, which ranks countries using over 100 variables, from labour markets to government institutions to property rights. The bank found that there’s an incredible amount of variation among the euro zone’s member nations. The biggest differences come in pay and productivity, the efficiency of the legal systems in settling disputes, anti-monopoly policies, government spending and the quality of scientific research.

Indeed, the euro zone countries are more different from each other than countries in just about any hypothetical currency union you could care to propose. A currency union for Central America would make more sense. A currency union in East Asia would make more sense. A currency union that involved reconstituting the old USSR or Ottoman Empire would make more sense. In sum, “a currency union of all countries on Earth that happen to reside on the fifth parallel north of the Equator would make more sense.”

But the currency union went ahead because of the political ambitions of France and Germany to have a Europe led by them, even after British capitalism refused to join. Of course, the aim was to bring about a ‘convergence’ between the weaker and stronger economies. That dismally failed in the boom years of 2002-7. The Great Recession just exposed and widened the inequalities.

Can the existing currency union survive? Well yes, if economic growth returns big time and/or if German capitalism grasps the nettle and is prepared to pay to help the ailing smaller capitalist economies through fiscal transfers. It is no good the Germans saying they will do so if the likes of Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain etc “stick to fiscal targets”. They cannot. So Germany will have to decide on more transfers without more austerity. Yet the red lines being imposed by the Germans are precisely to avoid recognising the need to transfer funds to the weaker capitalist economies like Greece.

The reason the Germans are baulking at this is that a proper fiscal union would not be cheap. The Cologne-based IW economic research institute reckoned that West Germans paid about $1.9 trillion over 20 years, partly via a “solidarity surcharge” on their income taxes, to help integrate and upgrade Eastern Germany. That was roughly two-thirds of West Germany’s GDP then. The subsidies helped cover East Germany’s budget shortfalls and poured money into its pension and social security systems. At the same time, nearly 2 million East Germans — a full one-eighth of the population — moved west to seek work. That is the sort of transfer of funds and jobs that will have to take place to support the currency union. Currency unions cannot stay still – Europe’s has been around for only 15 years. Either they break up or they move onto full fiscal union where the revenues of the state are pooled.

Take Federal Germany itself. There is a mechanism of fiscal transfer between the federal states of Germany, the so-called “Länderfinanzausgleich”. The German constitution states that the objective of this fiscal transfer mechanism is the convergence of the financial power across its federal states. The current system consists of vertical payments between the German state (“Bund”) and the federal states (“Länder”) as well as horizontal payments from federal state to federal state. The eligibility for transfer payment receipts is determined by an index (“Finanzkraftmesszahl”) which indicates the relative financial power of the federal states. Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg and Hesse are currently the only net contributors, while Berlin is the biggest net recipient of these fiscal transfers.

In Germany, fiscal transfers from the South to the North-East have certainly helped these federal states to converge in terms of their financial power and standard of living since the German unification in 1990. Nevertheless, after 25 years of fiscal transfer payments, the economic situation in these states remains highly unequal. For instance, the German unemployment rate varies significantly across federal states.

Of course, the rich Lander of Bavaria and Hesse are complaining that they are taking too much of the burden in Germanys’ fiscal union for ‘profligate’ Lander like Berlin and Saxony in East Germany. But that is the point in a nation state: as Gordon Brown, former UK Labour PM, put it during the Scottish independence referendum last September, a nation state with fiscal union means “from each according to means; to each according to needs” – shades of communism!

Take the example of the UK. This is a government of four nations and many regions. Taxes are raised by a central state (although there has been some devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) and raising debt is mostly made by the central state (there are some local government bonds or loans). Wales is a poorer part of the UK. It runs a ‘trade deficit’ with the rich south-east of England. Its inhabitants contribute way less in tax revenue than they receive in government handouts. So Wales has twin deficits on its government and capitalist sectors, just as Greece has with the rest of the Eurozone.

Tax revenue per is 26% lower in Wales (at £5,400) and 23% lower in Northern Ireland (£5,700) than in UK as a whole (£7,300). Wales and Northern Ireland have less income and wealth than the rest of the UK and correspondingly raise less revenue per person from all the main taxes. While the public finance deficit in England was approximately £2,000 per head, it was £6,000 in Wales: a difference of £4,000: a combination of higher public spending of £1,383 and lower tax generation of £2,400. It’s because of higher public spending on tax credits, income support and on housing benefits in Wales with its lower wages, higher unemployment and greater social. Fiscal transfers within a fiscal union ameliorates (but does not eliminate) these disparities.

Tax revenue in Scotland (£7,100 per person in 2012–13) looks much more like that in the UK as a whole (£7,300). But public spending per person has been higher in Scotland than the rest of the UK and roughly 20% greater than in England. So Scottish ‘budget deficits’ are higher than in England. Devolution of spending and revenues to Scotland is gradually eroding the UK fiscal union.

Sometimes there are grumbles from the rich south in the UK that they have to pay for the unemployed Welsh but that argument does not have much traction. After all, the extreme logic of that is to say that the very rich inhabitants of Kensington in the posh part of London should not have their tax revenues redistributed to the poor inhabitants of Wales or the north of England. That would mean Kensington would have to break with the fiscal and currency union that is Britain, put up border controls and find their own government, armed forces and central bank. Of course, their riches would soon disappear because they are based on the labour of all the people in Britain and even more from abroad. It is a point that many nationalist elements in Germany and northern Europe forget. If the Eurozone breaks up into its constituent parts, the ongoing (not just immediate) losses to GDP for northern Europe would be considerable.

The example of the US also shows the advantages of a federal state over the commonwealth of states that existed to begin with. It took a civil war of bloody proportions to establish a unified state that wiped out the idea of secession for good. Now the US federal government raises taxes and debt and provides funds to the states (even though they raise their own taxes). A full financial union came later than fiscal union in the US, when the Federal Reserve Bank was set up by the large private banks after a series of banking collapses. Now dollars are redistributed through the federal reserve system to cover ‘deficits’ on trade and capital between states. As a result, while the average national tax revenue per head is about $8,000, rich states like Delaware, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Minnesota and Connecticut pay 25-50% more per head while poor states like Alabama, Missisippi, West Virginia, Kentucky or Michigan, or ‘empty’ states like Montana pay 25-50% less than the average.

I argued back in the middle of the Euro crisis in 2012 (https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/05/10/eurozone-debtmonetary-union-and-argentina/) that in the absence of German capitalism bailing out the south with huge fiscal transfers, the only way that the peripheral countries could restore growth and avoid the break-up of the EMU is by defaulting on the debt they have accumulated – in effect a forced fiscal transfer. And so it seems for Greece.

Growth has not been restored by the neoliberal solutions demanded by the Euro leaders and the Troika. The OECD keeps claiming that ‘structural reforms’ will deliver a rise in the level of GDP per capita for the indebted member states (see the recent OECD report for the G20 meeting, http://www.oecd.org/g20/topics/framework-strong-sustainable-balanced-growth/ambitious-reforms-can-create-a-growth-path-that-is-both-strong-and-inclusive.htm).

But what are these wonderful growth-enhancing structural reforms? For Portugal, the Troika decided that they were a reduction of four public holidays a year, three days less minimum annual paid holidays, a 50% reduction in overtime rates and the end of collective bargaining agreements. Then there would be more working time management, the removal of restrictions on the power to fire workers, the lowering of severance payments on losing your job and the forced arbitration of labour disputes. In other words, workers must work longer and harder for less money and with less rights and a higher risk of being sacked. Southern Europe must become a cheap labour centre for investment by the north. That’s the Troika’s reforms.

Then there is deregulation of markets. Utilities are to be opened up to competition. That means companies competing to sell electricity or broadband to customers who must continually change their suppliers to save a few euros. Pharmacies are to have their margins cut, so small chemists are to earn less but there is no reduction in the price of drugs from big pharma, the real monopolies. And the professions are to be deregulated, so lawyers cannot make such fat fees but anybody can become a teacher or taxi driver or drive a large truck with minimal or no training. Finally, there is privatisation of the remaining state entities sold cheaply to private asset companies in order to pay down debt and enlarge the profit potential of the capitalist sector. It’s more or less the same proposals for Greece, Spain, Italy and Ireland.

The real aim of these neo-liberal solutions that the EU leaders and the OECD (now apparently an agreeable institution to deal with by the Syriza government) is not to restore growth as such, but to raise the rate of exploitation of the workforce. This would boost profitability and so the private sector will then invest to create jobs and more GDP, assuming, of course, that capitalism does not have another slump before then.

Such policies have not worked so far. And in the case of the weaker capitalist economies of the Eurozone they have been disastrous. Ireland and Estonia have been offered up as examples of successful neoliberal policies, but as I have explained on many occasions, the reality is that growth and exports in Ireland and Estonia have only come about through huge deleveraging of private sector debt (at public expense), massive emigration and substantial social funding by the EU (some fiscal transfer there).

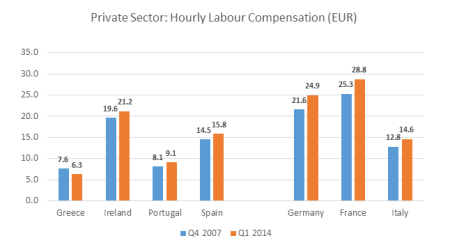

For Greece, mass emigration is taking place but debt deleveraging has not yet. Yes, real incomes have been slashed and unit labour costs in Greece are now nearly on a par with Germany (see my post). But will this be enough to get the Greek economy going now that it is ‘competitive’ in price? Hourly wages have come down substantially in Greece and are in fact the lowest in the euro area with the exception of Latvia and Lithuania.

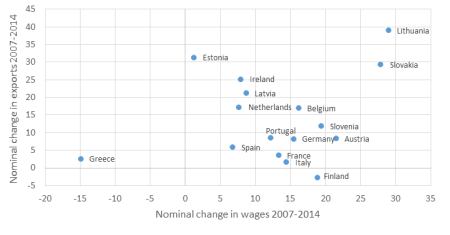

But despite a significant wage adjustment, exports have not picked up as they did in other countries.

Nominal change in exports is given as % of 2014 GDP. Nominal change in wages calculated as nominal % change between Q4 2007 and Q1 2014

What this tells you is that Greece’s capitalist sector is so weak and inefficient that even with a modest pick-up of profitability and huge drop in labour costs, it cannot compete in world markets. But it has had an ‘internal devaluation’ of labour and product costs, so if it exits the Eurozone now, a further currency devaluation may well not improve things at all, even on the export front, or at least only for a few years, as it did in Argentina. But that would be at the expense of forced deleveraging as the Greek capitalist sector defaulted on its euro debt and went bust.

Weak Greek export performance is due to the rottenness of the oligarchies in the major industries in Greece, the failure of the Greek banks to provide credit to small businesses with any innovative products and the failure to invest in new technology by the major firms. Greece’s biggest goods export is refined oil products. If Greece ever wants to develop a stronger manufacturing capacity to compete in world markets, it needs the support of funding from the rest of the Eurozone – lower debt, fiscal transfers and investment funding for shipping (6% of GDP), agriculture, alternative energy (sun and sea) and tourism (6% of GDP) and other services that Greece can offer. And that means public investment. And it means cooperation and support from the rest of Europe.

Fiscal union must be part of that cooperation. But it is unachievable in a capitalist European Union, where the national interests of the richer member states are put before a union of ‘equals’. The German view of fiscal union involves a binding agreement between all members to run national budgetary policy so that no inter-country fiscal flows would ever be necessary! This is impossible to achieve, even if the Eurozone was growing at a reasonable pace, which it is not.

The idea that a central eurozone budget would gradually grow in size (from its tiny 1% of Euro GDP), towards a full federal fiscal union is a pipedream in a Eurozone with big strong states, a huge bureaucracy an ‘independent’ central bank and a feeble European parliament – in other words, no democratic commitment to a federal Europe. Instead, we have a botched, in-between solution, with no democracy, where there flows of resources from the strong national economies to the weak, only though Euro institutions and tied to draconian fiscal targets. The red lines set by the Euro leaders in the negotiations with the Greeks demonstrate that.

Fiscal union, indeed a proper democratic federation of Europe, would only be possible through the ending of the capitalist mode of production and its replacement by one based on common ownership and resources transferred from ‘each according to means and to each according to need’.

1 comment:

The U.S. federal minimum wage is $7.25, but 29 states have enacted higher minimums, and there are exemptions in some states, such as Oklahoma allows a $2 minimum in small businesses with less than $100,000 of sales. But in California only 1.8% of the workforce earns the federal minimum or lower, while in Texas and Georgia it's as much as 8% of the workers. The chart in this article shows Greek wages one quarter of French wages, a very wide differential. In the U.S. federal expenditures vs. tax extraction varies state by state, of course, but the public will is strong to equalize the bare social minimum standards. The minimum standards are very low, I've researched and discovered that 40% of U.S. workers (61 million of 156 million) receive collectively in wage income only 4% of total U.S. income --- precisely, the collective income of 40%, all with incomes below $20,000, is $504 billion while the total US income is over $14 trillion. One tenth of households extract 50% of all "market" income. 20% of households extract 60% of "market" income. The lower-earning 40% of households extract 12% of all income. The "minimum standards" for income are very low even with a $7.25 per hour minimum wage. It appears to be a task for the majority of non-supervisory workers to set higher wage rates for themselves through a political process. This was a very enlightening article, well done. I write a blog, http://benL8.blogspot.com - I posted this also at M. Robert's blog. Thanks R.

Post a Comment