The recent massive demonstrations against the Macron administration in France forcing through so-called pension reforms reveals the determined attempts of pro-capitalist governments in all the major economies to cut real wages when we are old and can no longer work.

The Macron government has forced by decree a ‘reform’ that raises the pension age to 64 years from 62 years. In Spain, where the retirement age has been fixed at 65 years for decades, the government is opting for an alternative solution to the so-called pensions problem. It is going to increase contributions from the incomes of younger higher earners to pay for older retirees.

Pensions are really deferred wages, deductions from income from work to pay for a decent income when people retire. After decades of work (and exploitation), workers, male and female, should be entitled to stop and enjoy the last decade or so of life without toil without being poverty. Literally, they will have earned it. But capitalism in the 21st century cannot ‘afford’ to pay decent living incomes as state pensions when workers retire. Why? Well, the mainstream arguments are several-fold.

First, the demographic trends, particularly in the advanced capitalist economies, mean more people are reaching retirement age and fewer people are at working age. So the argument goes, higher ‘age dependency rates’ mean that those at work have to pay more in taxes for those who are not working. For example, in Spain there are three people of working age for every single pensioner; by 2050 that dependency ratio will be just 1.7 to one.

The second argument is that life expectancy has risen so much and people are much healthier, that the ‘gap years’ between stopping work and dying have risen far too much. For example, Spain’s life expectancy is 83 — one of the world’s highest. So people should work longer to reduce that gap to where it was before.

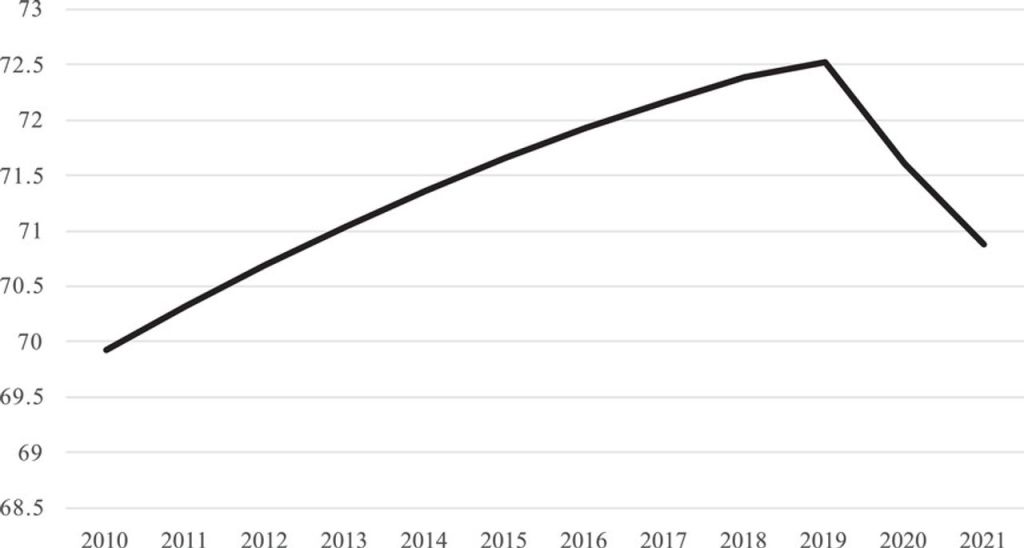

The cruel irony is that the pensions cuts that the French and Spanish governments seek to impose for reasons of demography are taking place when life expectancy in the major economies has started to fall. In the first decade of this century, life expectancy increased by nearly three years every decade. But now life expectancy at retirement is two years less than previously expected.

World average life expectancy (years at birth)

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/padr.12477

And what is ignored is the huge disparity in life expectancy between lower income people retiring and very dependent on state pensions and better-off people with additional company pensions. For example, almost eight years separates the life expectancy of retirees living in exclusive parts of London like Kensington and Chelsea to those living in Glasgow. A 60-year old man in the Scottish city might live a further 19 years. For his London contemporary that rises to 27 years. In both places women live almost three years longer than men. Indeed, the fall in life expectancy in the UK has forced the government to delay until 2026 raising the retirement age (already at 67 years) to 68 years.

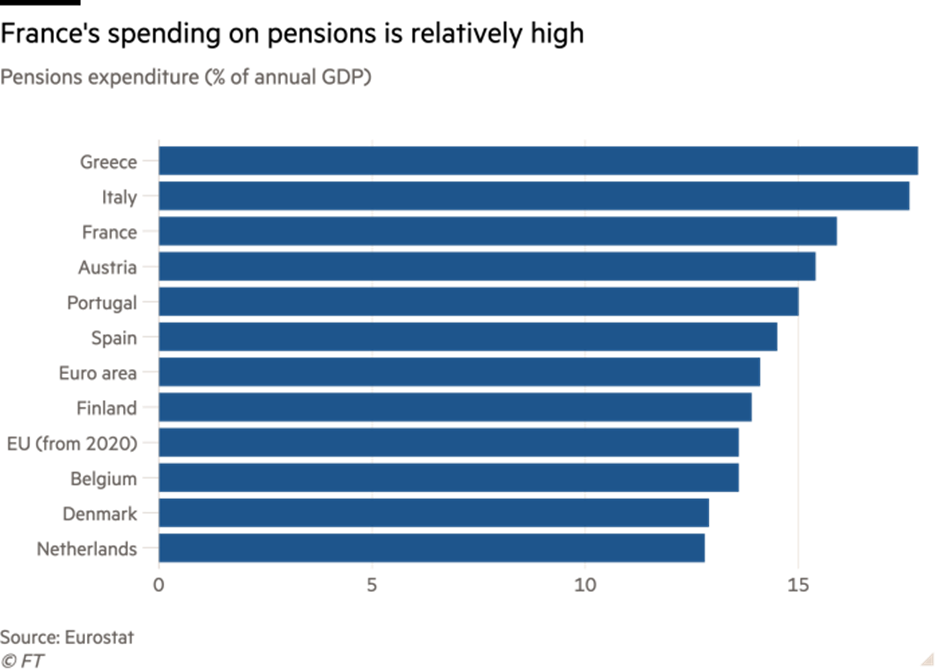

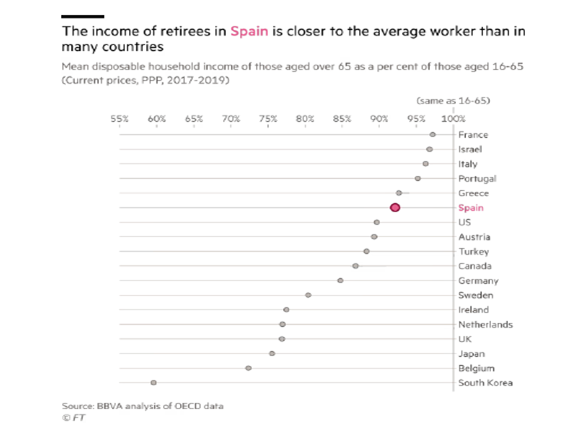

And the third argument is the cost to the public purse. The argument is that too much public money goes to pensioners, thus reducing available funds for other important public services and benefits. Governments are forced into running budget deficits that increase public debt and so raise interest costs that eat into public spending. It’s true that pensions in France are higher than most other EU countries. And Spain’s net pre-retirement income average at 80% is actually ahead of France’s 74 per cent and an average of 62 per cent in the OECD.

But does that mean the aim should be to ‘level down’ pensions to those of the UK, for example, which has one of the lowest state pensions relative to average earnings in the OECD? Surely, the aim should be to ‘level up’ to the best?

And the pensions deficit in France is tiny compared with the cost of measures introduced in response to the pandemic (€165bn) and the energy shock (around €100bn), as well as President Macron’s commitments to invest more in nuclear power (€50bn) and defence (€100bn by 2030).

Nevertheless, mainstream economists continue to see the ‘problem of pensions’ as causing excessive government spending and deficits. Here is what one such analysis put it in vigorously supporting Macrons’ attack on French state pensions. “France’s pension reform, centred on prolonging the age of retirement to 64 from 62, should ensure the progressive rebalancing of the pension system by 2030, given unfavourable demographic trends and a widening deficit. The reform sends a strong signal to European partners and international institutions of France’s intent to preserve medium-term fiscal sustainability and introduce supply-side reforms.” So it’s to encourage the others to level down.

Similarly, that paper for capitalist strategy, the UK’s Financial Times, called Macron’s move ‘indispensable’. “Plugging a hole in the pension system is a gauge of credibility for Brussels and for financial markets which are again penalising ill discipline.” The FT went on: “If unchanged, the (French) pension system will run annual deficits of between 0.4 per cent and 0.8 per cent of gross domestic product over the next quarter-century; (there are more benign scenarios of break-even, but these suppose a productivity miracle). It is not a catastrophic hole: the minimum contribution for a full pension is already quite exacting at 41.5 years — and it is climbing to 43 — even if a pension age of 62 looks generous. Yet it is a hole that needs to be filled.”

Two things here. So this (not so large) deficit hole has to be filled? Even if we accept that it does, why does it have to be filled by forcing people to work longer or make higher contributions from their wages now to pay for pensions later? And also, note that “there are more benign scenarios, but they suppose a productivity miracle’. And this is the crux of the ‘pensions problem’. Without recognizing it, the FT exposes the mainstream arguments as bogus.

Ten years ago, I called the ‘pensions crisis’ (yes, it was doing the rounds then) a myth. Then I put it this way: “There are enough resources if they are properly organised and fully used. It’s both a political choice and question of economic organisation. Does a country want to use its resources so that people can stop work at the age of 60 or 65 and have enough income to live on in reasonable comfort, or not? It can be done.”

It depends on two things: first, that an economy creates enough resources and expands sufficiently to cater for its elderly population that may also be getting larger as a share of the population. And second, given finite resources, decent pensions can be provided by cutting out other calls on government revenues i.e. such as bailing out the banks; increased arms spending; more subsidies for private corporations to invest in fossil fuels; and lower taxes for top earners and corporations etc.

It is not a choice between good pensions or a good health service or education system. Ten years ago, I showed that just a 1% pt sustained rise in average real GDP per capita in the major economies could deliver enough extra revenue to governments to easily maintain current pension levels and terms with something to spare. And that would be without changing the allocation of public money to defence (now set to increase in all EU economies to at least 2% of GDP each year) or chasing down the tax havens and avoidance schemes by which companies and rich individuals lose revenues for governments by up to 10% a year.

And I emphasise the word a ‘sustained’ increase in real GDP growth. Every 8-10 years, capitalist economies have slumps in output and investment which significantly hit government revenues and often lead to substantial bailouts of banks and multi-nationals, further reducing revenues to pay for public services and pensions. A planned economy, where production is not based on profitability and not subject to regular and recurring crises, could soon ‘afford’ decent pensions.

Instead, in the 21st century, capitalist economies are experiencing slowing economic growth and already three slumps, with the prospect of another right now. The World Bank has just published a truly shocking report on the prospects for the world economy for the rest of this decade. The Bank reckons that the world’s maximum long-term growth rate is set to slump to a three-decade low by 2030. Between 2022 and 2030 average global potential GDP growth is expected to decline by roughly a third from the rate that prevailed in the first decade of this century—to 2.2% a year. For countries like France, the growth rate will be well below 2% – indeed just 1.2% a year.

Given that the working age population in France, like many other advanced economies in the Global North, is set to fall further in the rest of this decade, growth depends higher productivity from a shrinking labour force (unless governments force people to stay in work longer or work longer hours). But productivity growth is slowing to almost a trickle as investment in value-creating sectors of economies stagnates. So increased productivity is unlikely to compensate for a declining labour force.

And there is no answer to be found in privatising pensions. Already, corporate pension schemes are failing to meet workers needs. First, private pension managers take a sizeable cut in fees for managing pension funds.

Second, these investment managers cannot deliver sufficient returns on investing in stocks and bonds, so that private pension funds often go into deficit. And pension fund managers resort to risky investments to try and boost returns. That can lead to crises and losses – for example, the meltdown in UK pension funds in so-called “liability driven investment” schemes (LDI) last year when bond yields rocketed, forcing the Bank of England to provide emergency credit of £65bn.

And third, most private schemes are no longer ‘final salary’ ie pensions based on your wage when you retire, but on the amount of contributions you make from your wages as you go, and so relying on pension fund managers to invest wisely. Private pension schemes are a con – and anyway, most workers do not have one.

The French option for state pensions is to raise the retirement age so that people have to work longer. And that includes those who do tough, physically or mentally, stressful work that cannot be continued for more than a few decades, if that. Some might say that even 64 years is ok because in many countries the retirement age is way higher (at 67 years in the UK now). But the majority of French people do not agree. For them, the pension age was a hard fought right, along with better social services that people do not want to lose.

As one French sociologist put it: “For 40 years, successive governments have been asking the French people to accept ‘reforms’ reducing social rights. These have degraded public services in health, education, transport and so on, while eroding purchasing power and worsening working conditions … The French are fed up.”

No comments:

Post a Comment