by Michael Roberts

China is in deep trouble. Its zero-COVID policy has failed; the

economy has slowed to halt; it now has a falling and fast-ageing

population; it is in the midst of a property and debt crisis; so it is

heading for a permanent, low productivity growth stagnation like Japan.

Xi’s leadership is in crisis as he flails about swinging from one

policy to another. And the risk is that the ‘aggressive nationalism’ of

the CPC will lead to military action against ‘democratic’ Taiwan, just

as Russia did with Ukraine.

That’s the line of the Western economic experts and the media on a daily basis. All these arguments have been raised before and for that matter for the last 20-plus years: namely, that China is about to implode and the CP-control is about to collapse. I have provided balanced answers to all these issues many times before, in particular in a series of three posts only last October. So what can I add to the latest round of ‘expert’ speculation on the future of the Chinese economic model’?

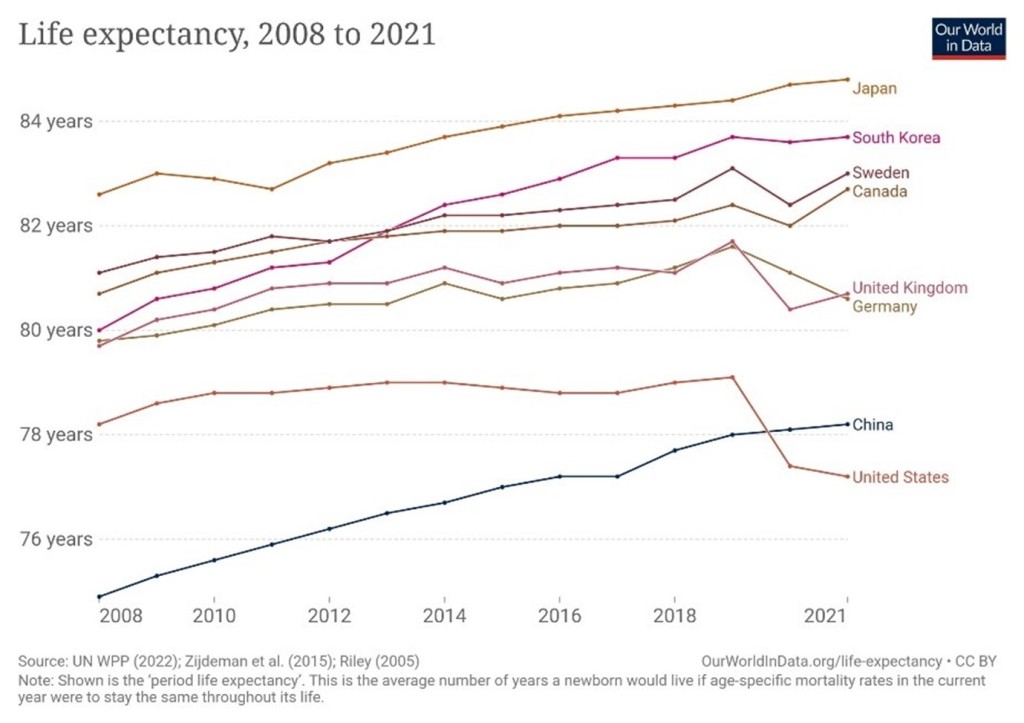

Well, the first obvious addition is the end of China’s zero-Covid policy. The experts paint this as a failure of the previous policy of the last three years. And yet in those three years, millions of lives were saved. John Ross gives us a comparison: if the world per capita death rate from Covid had been kept as low as China’s there would only be 29,000 Covid deaths globally instead of 6.7 million, while in the US there would have been only 1,200 deaths instead of the 1.1 million which actually occurred. So great is the impact of this US failure that after the pandemic China’s life expectancy, at 78.2 years, is now significantly higher than the US at 76.4 years.

At the same time, China did not slip into a slump in 2020 unlike every other major economy; and indeed, increased the size of its economy in real terms and raised average living standards, while most major capitalist economies are only now getting back to the level of pre-pandemic 2019, as they now experience a dismal cost of living crisis.

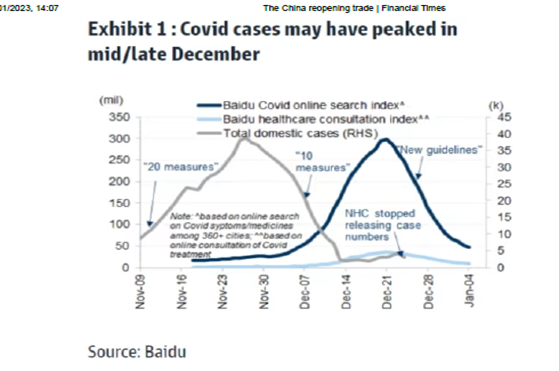

The zero-COVID policy was clearly exhausted by the end of 2022. New COVID variants were spreading and the government had to give way on the policy – but at least by now the majority of the population had been vaccinated and the health service capacity raised – if still insufficient to deal with the rise in infections. Deaths are up, but not anywhere near the level projected by Western experts. I explained this in a recent post. We shall see if the rise in cases accelerates during the Chinese New Year holiday starting now.

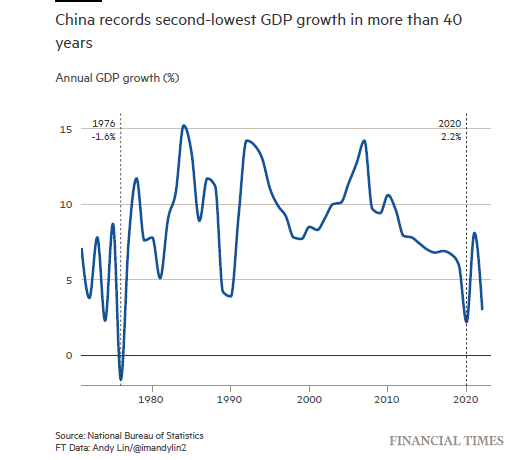

The media are making much of the fact that for the first time since the 1990s, China’s real GDP growth this year was lower than the average growth in the East Asian region. In 2022, real GDP was up only 3%, well below the long-term target of about 5-6% a year.

Why the slowdown? Clearly over the last three years, China’s zero COVID policy played a role in suppressing economic activity. But China opted to save lives over economic expansion. The other reason that China’s economic growth has slipped is the general slowdown towards a slump in the rest of the world. The major capitalist economies are stuck in supply-chain congestion, weak investment expansion and now rising interest rates and inflation that threaten outright global recession this year.

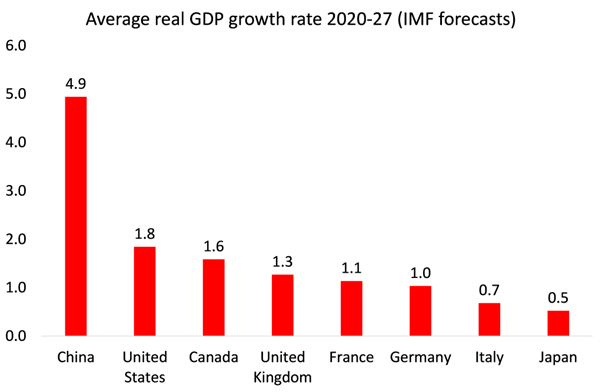

But China is not heading into a slump like the G7 economies. Indeed, both the World Bank and the IMF expect China’s real GDP to rise by over 4% this year, while the most G7 economies will be contracting or have near zero growth. If we take the years 2019-23, China’s economic growth rate will have been at least three times as fast as the US and more than five times as fast as the EU – and that’s assuming no slump in the latter economies this year.

Looking longer term, Western analysts reckon China is heading for much slower growth and this will threaten Xi’s future. Up to now, China’s unprecedented economic growth record has been based on high investment rates and exports of manufactured goods to the rest of the world. But from hereon, the Western analysts claim that China will enter a period of low growth and will not escape the ‘middle income trap’ that so many so-called emerging economies are locked into. China will not catch up even with the GDP level of the US as previously expected.

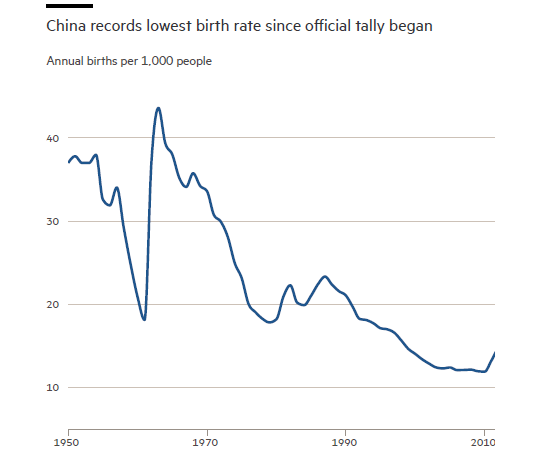

This claim is based on two assumptions. First, that China’s ageing population and declining working-age sector will reduce growth rates; and second that the high-saving, high-investment model of Chinese growth no longer works. China’s National Bureau of Statistics announced that the total population fell by 850,000 in 2022 to 1.41175bn, the first decline in 60 years. The birth rate in 2022 was the lowest since records began more than seven decades ago — 6.77 births for every 1,000 people, down from 10.41 in 2019.

The UN has projected that China’s population will fall to 1.31bn by 2050 and 767mn by the end of the century. The 2050 estimate would still make China 3.5 times larger than the US, which is projected to have 375mn people by then. But it is currently 4.7 times larger than the US. The UN’s 2022 estimates also project that India will overtake China as the world’s most populous nation this year. India’s population currently stands at 1.4066bn. But what’s missing from that stat is that India will remain a predominantly rural agricultural population way behind China, now mainly an urbanized and industrialised people.

Nevertheless, the Western experts continue to make much of China’s demographics. “This is a truly historic turning point, an onset of a long-term and irreversible population decline,” claimed one Western-based expert on Chinese demographic change, Wang Feng, at the University of California, Irvine. “China cannot rely on the demographic dividend as a structural driver for economic growth,” said Zhiwei Zhang, president and chief economist at Pinpoint Asset Management. The argument goes that China won’t be able to grow as fast as before now that the working population is declining and there will be an insufficient rise in the productivity of labour to compensate. I have discussed these arguments at length in previous posts.

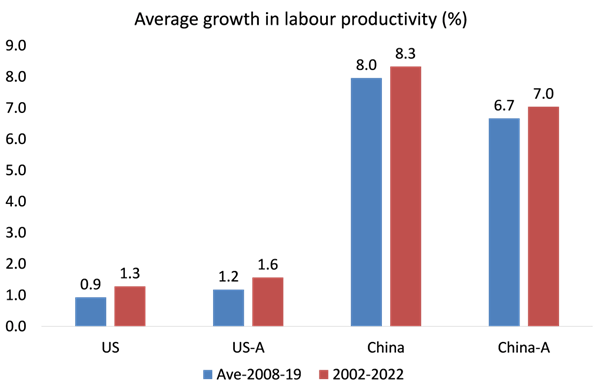

The arguments are weak and faulty. Indeed, even on the adjusted (A) Western (Conference Board) measures of labour productivity growth during the COVID period, China has done way better than the ‘dynamic’ USA.

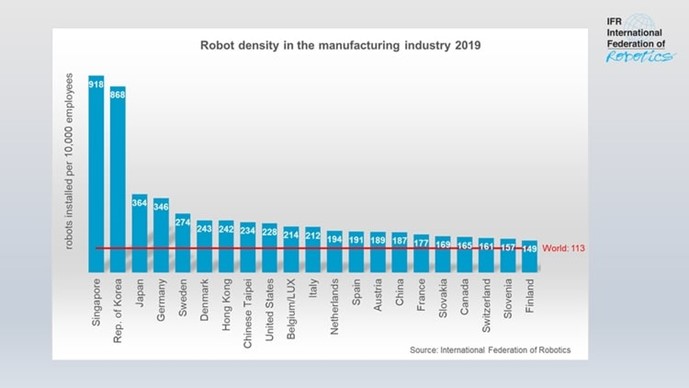

The answer to the demographic decline is a rise in the productivity of the existing workforce. And China is taking steps to ensure just that. China is the leader in industrial robots with a rise from 69,000 units in 2015 to 300,000 units last year; although of course, it is still well behind on robots per person – yet ahead of France, the UK and Canada before the pandemic.

Longer term, the IMF forecasts that China will grow at a subdued rate of 5% a year. But that rate would still be more than twice as fast as the US, and more than four times as fast as the rest of the G7 – and that’s assuming no slump in the G7 economies in the next five years.

The other argument of the Western analysts is that China cannot grow at any reasonable pace from hereon, unless it switches from a high-savings, high-investment, export-oriented economy to a traditional consumer-led capitalist economy existing in most of the major capitalist economies, particularly the US and the UK.

The usual basis for this view is that personal consumption rates are too low in China and this will hold back demand-led growth. For example, take this view by Chen Zhiwu, a professor in Chinese finance and economy at the University of Hong Kong. Chen argues that, under Xi, major reforms towards a larger private sector, consumer-led economy have been sidelined. “The 60 reforms would have largely expanded the role of consumption and private initiatives,” he says. “However, the market-oriented reform agenda has been largely sidelined . . . resulting in a larger role for the state and a shrunken role for the private sector.” According to Chen, this will mean China’s economy will stagnate from hereon.

Another prominent and widely-followed Western analyst, Michael Pettis, who is based in Shanghai, makes a similar argument, namely that what will push China into Japanese-style stagnation is the failure to expand personal consumption and continue to expand investment through rising debt. And only this week Keynesian guru Paul Krugman joined the chorus, talking of China’s “wildly unbalanced” economy, which Krugman claims: “For reasons I don’t fully understand, policymakers have been reluctant to allow the full benefits of past economic growth to pass through to households, and that has led to low consumer demand.”

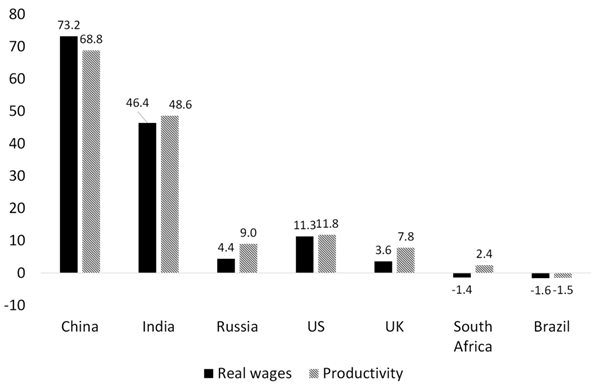

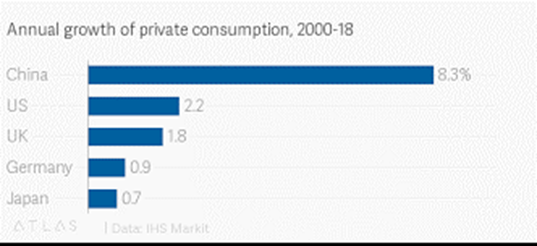

Unfortunately, sections of the Chinese leadership, particularly their economists in the finance sector, accept this annoyingly stupid argument from the Western experts. How can anybody claim that the mature ‘consumer-led’ economies of the G7 have been successful in achieving steady and fast economic growth, or that real wages and consumption growth have been stronger there? Indeed, in the G7 consumption has failed to drive economic growth; and wages have stagnated in real terms over the last ten years (and are now falling), while real wages in China have shot up.

This is the real point. Actually, consumption is rising much faster in China than in the G7 and that’s because investment is higher. One follows the other; it is not a zero-sum game. Pettis’ view is a crude Keynesian analysis that ignores even Keynes’ view himself that it is investment that grows an economy with consumption following, not vice versa.

And not all consumption has to be ‘personal’; more important is ‘social consumption’, that is, public services like health, education, transport, communications and housing; not just motor cars and gadgets. Increased consumption of basic social services is not accounted for in the personal consumption ratios.

China has a long way to go in social consumption too, but it is way ahead of its emerging market peers in many social areas and not so far behind leading G7 economies, who started more than 100 years before. I defer to Citibank’s economists in their recent in-depth study of the Chinese economy “In other words, it is quite possible for the Chinese economy to deliver greater opportunities for consumption without consumption being a specific target for policy: household disposable income has been growing faster than GDP in the real terms in the past few years (except 2016), a trend likely to extend into the future. At the same time, the unlocking of wealth effects should help the consumer.”

The real challenge for China’s economic future is how to avoid much of its investment going into unproductive areas like finance and property that have now led to serious problems. And also, in what way the growing contradictions between the state and capitalist sectors in China are being handled in Xi’s third term.

And on this issue, it is China’s large capitalist sector that threatens China’s future prosperity. The real problem is that in the last ten years (and even before) the Chinese leaders have allowed a massive expansion of unproductive and speculative investment by the capitalist sector of the economy. In the drive to build enough houses and infrastructure for the sharply rising urban population, central and local governments left the job to private developers. Instead of building houses for rent, they opted for the ‘free market’ solution of private developers building for sale. Of course, homes needed to be built, but as President Xi put it belatedly, “homes are for living in, not for speculation.”

Indeed Xi’s call for ‘common prosperity’ is a recognition that the capitalist sector fostered by the Chinese leaders (and from which they obtain much personal gain), has got so out of hand that it threatens the stability of Communist Party control. What Xi and the Chinese leaders have called the “disorderly expansion of capital”. The capitalist sector has been increasing its size and influence in China, alongside the slowdown in real GDP growth, investment and employment, even under Xi. A recent study found that China’s private sector has grown not only in absolute terms but also as a proportion of the country’s largest companies, as measured by revenue or (for listed ones) by market value, from a very low level when President Xi was confirmed as the next top leader in 2010 to a significant share today. SOEs still dominate among the largest companies by revenue, but their preeminence is eroding. This is intensifying the contradictions between the profitability of the capitalist sector and stable productive investment in China. The accumulation of financial and property assets based on huge borrowing is detracting from growth potential.

The other problem is the democratic accountability of the Chinese

government. China’s leadership is not accountable to its working

people; there are no organs of worker democracy. There is no democratic

planning. Only the 100 million CP members have

a say in China’s economic future, and that is really only among the

top. As a result, the CP leaders lurch from periods of expanding the

private sector and the market to periods of trying to restrict and

control it. Chinese workers are pawns in this game.

Branco Milanovic in a recent post recognized this, in what he called the attempt of the CP leaders to maintain ‘a middle line’, by favoring alternatively pro-leftist and pro-rightist policies. Xi has been following the former up to now, but now there are signs than the government wants to swing back towards pro-market policies to conciliate with Western interests, as US imperialism and its allies step up their policy of containment over China.

And indicator of the latest zig zag is found in Vice-Premier Liu He’s attendance at the jamboree of the rich in Davos, Switzerland. Li told the Davos audience that Xi Jinping’s “common prosperity” initiative is “definitely not to introduce equalitarianism nor welfarism.” Liu said the main point of the strategy is to avoid polarization, while admitting a certain level of income and wealth disparity is inevitable. “What we want to emphasize is that it is about equality of opportunity and not equality in results,” the vice premier said, sounding like a good pro-capitalist Western politician.

Li privately met a group of top corporate executives in Davos to tell them that the world’s second-largest economy was back, in an effort to rekindle economic ties damaged by the pandemic and tensions with the US. He told them that “Some people say China is trying to move toward a planned economy, but that is absolutely not possible.” The conclusion of the corporate leaders was that “They are reversing everything that has been done in the last three years; they will be business-friendly and [know] that the economy cannot be successful without the private sector.”

It is now crystal clear that the US, enabled by a bipartisan

consensus in Washington, is determined to stop China upgrading

technologically. China is now treated as “an enemy” of the US. Without

the involvement, backing and control of workers organisations, the

Chinese CP government is leaving itself open to imperialist

encirclement. So the zig zags of CPC policy are wasteful, inefficient

and dangerous to China’s future.

No comments:

Post a Comment