by Michael Roberts

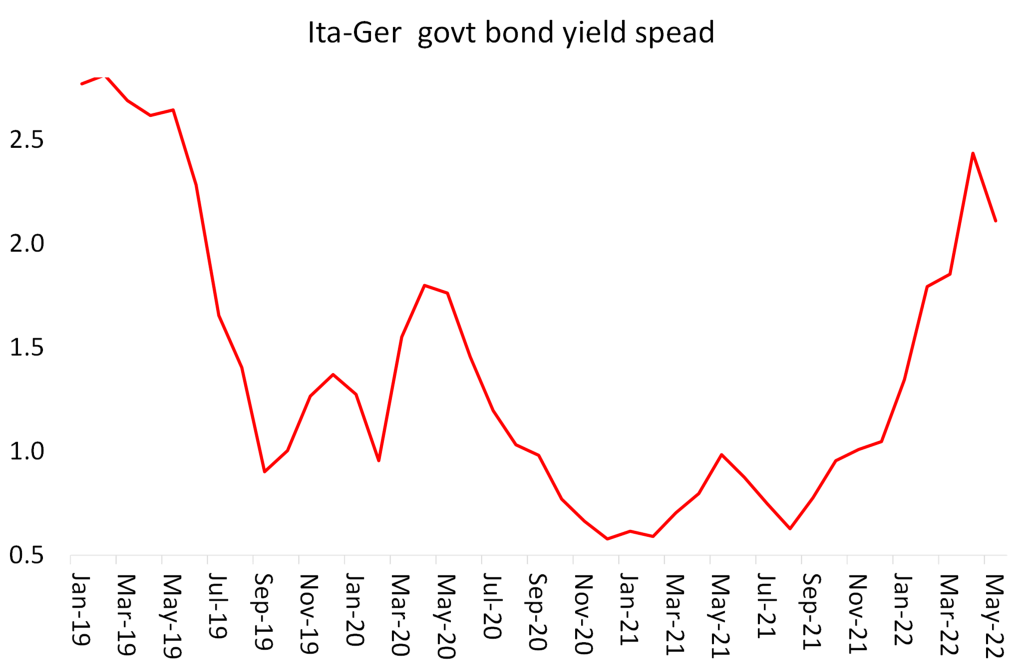

It’s been a big week for the major central banks. First, the European

Central Bank (ECB) called an emergency meeting because government bond

yields were rising sharply in the more indebted Eurozone economies like

Italy and Spain. That threatens to deliver a new sovereign debt crisis

as happened after the Great Recession from 2010-2014, leading to the Greek nightmare.

The ECB is now looking for ways to fund the weaker Eurozone governments by buying more of their debt and ‘printing’ money to do it. Ironically, having just announced that it had ended quantitative easing (QE) and looked to raise interest rates in July in order to control accelerating inflation, the ECB now had to revert back to QE for the likes of Italy.

Then the US Federal Reserve announced a hike in its policy rate (the Fed Funds rate) by an extra-large 75bp, with more to come, as it also tries to control accelerating inflation. And last Thursday, the Bank of England joined in by raising its policy rate to control an inflation rate heading towards double-digits.

Only the Bank of Japan (BoJ) resisted increasing its policy rate, preferring to try and protect an already weak recessionary economy which continues to have relatively low inflation. But the BoJ noted that, by having much lower interest rates than other economies, the price of the yen in dollars and euros had started to plummet. That might help Japanese exporters, but it would also add to imported inflation. Indeed, as foreign investors sold off their Japanese government bonds (with government debt at GDP now at 270%), the BoJ would have to buy yet more bonds to fund government spending.

Central bank ‘policy rates’ set the floor for interest rates for banks, households and corporations, where rates will be correspondingly higher. And the Fed hike of 75bp is the most in one go for 28 years.

Ostensibly, the purpose of raising central bank policy rates is to force up interest rates for borrowing by banks, households and corporations. This will eventually reduce spending on homes, consumer products and investment in financial assets like stocks and bonds, and also productive investment in equipment, building and software. That supposedly will eventually cool overall demand and so inflation rates will subside.

But will it work; or even more, will it work without engendering a slump in the major economies? The answer lies partly on whether you accept the mainstream arguments on what causes inflation to rise. I have discussed this at length in various posts. The first main theory is monetarist; namely central banks ‘print’ too much money relative to output of goods: ‘too much money chasing too few goods’; and so price inflation rises. If central banks raise rates and reduce the amount of money they print then inflation will subside.

Fed chair Jay Powell still seems to adopt the monetarist approach when explaining to the US Congress in the latest Fed Monetary Report on how central banks can control inflation: “The inflation rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the Committee has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for inflation.”

Really? All the evidence of the last 60 years shows that monetary policy is not the driver of inflation or disinflation and is, at best, a secondary reacting factor. The real driver is the relationship between the productive output in an economy and the demand engendered by incomes from capitalist companies and workers households.

But that does not mean that it is ‘aggregate demand’ that decides the level of inflation and in particular, the demand generated by too much ‘wage pressure’. This is the Keynesian argument for inflation: ‘excessive demand’ and ‘wage-push’ on costs. The latest exponent of the Keynesian ‘excess demand’ theory is former US Treasury secretary and Keynesian guru of ‘secular stagnation’, Larry Summers. He forecast rising inflation rates back in 2021 because of too much government spending used to get out of the COVID slump. He called for government ‘austerity’ as the answer.

Now in a recent paper, he argues that inflation rates are being measured artificially low compared to the last inflationary spiral of the 1970s. That’s because how housing costs are calculated in the current inflation index have been altered compared to the 1970s. In 1983 a concept of “Owner’s Equivalent Rent” (OER) was introduced instead of actual home prices or mortgage payments. Summers argues that using the OER to measure housing prices lowers the inflation rate compared to the measure used before. This means that inflation now is really much higher than the official rate. So, to get inflation under control, the Fed will have to hike its policy rate much more than it thinks it needs to. Already, the Fed’s planned hikes would take the policy rate up to 3.5%, a massive increase in a short time. If it has to be closer to 5%, that really threatens to bring the whole house of cards down.

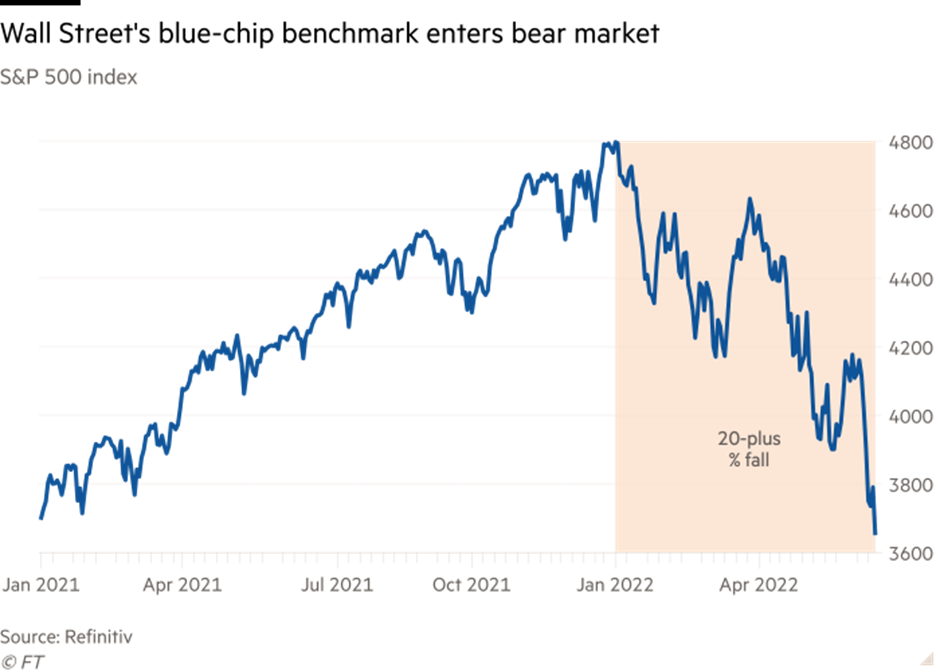

The first to go is usually where what Marx called ‘fictitious capital’ has accumulated ie financial assets and property. Higher rates make fixed income assets relatively more attractive, reducing demand for stocks, whose prices then fall. Already ‘Wall Street’ stock prices have dropped more than 20%, which is considered ‘bear market’ territory.

And the prospect of fast rising interest rates has hit that other great bubble in financial assets: cryptocurrencies. Bitcoin prices are down 45% on the year, at $21,000 a coin. It now costs more ($25,000) to mine it. So not only are crypto speculators taking a huge hit but so are those who mine it. More proof that crypto currencies are not alternative money to fiat currencies (those created by the state) but simply another speculative financial asset.

As I said in a past post: “In the last 20 years, financial fictions have been increasingly digitalised. High frequency financial transactions have been superseded by digital coding. But these technological developments have mainly been used to increase speculation in the financial casino, leaving regulators behind in the wash. When the financial markets go belly up, which they eventually will, the digital damage will be exposed.”

And then there is housing. Last week, US home mortgage rates jumped by the most since 1987 to reach 5.78%, the highest level since November 2008. The rate was 3.2% at the start of the year, while a year ago, before the Federal Reserve embarked on an aggressive campaign to raise interest rates, the 30-year fixed rate mortgage averaged 2.93%.

The increase since January from 3% to 6% now means 18 million fewer households can qualify for a $400,000 mortgage.

That’s a 36% reduction in potential demand. Home buyer affordability has plunged.

As a result, the previously booming US housing markets has started to topple over.

Where Summers and the Keynesians are wrong is that it is not excessive demand that has driven up inflation rate in goods and services that people use, it is the weakening of supply. The supply bottlenecks generated during the COVID slump globally have now been compounded by the Russia-Ukraine conflict, particularly in energy and food. I have discussed before the global food crisis that has already started. And the sanctions against Russian energy supplies are also accelerating prices for fuel and heating.

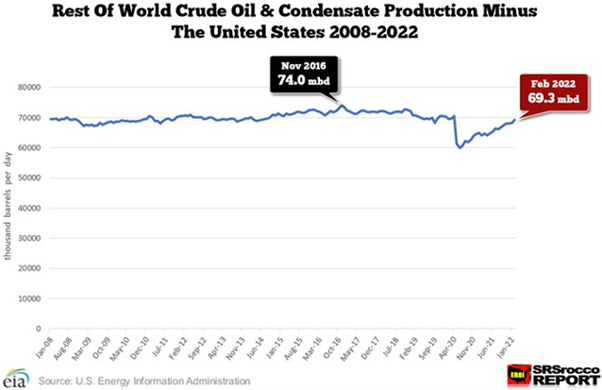

But here is the rub. Global production growth was already slowing before COVID. Take oil for example. Oil production outside the US had been static for years even before the COVID slump and was still below pre-pandemic levels before the Russia-Ukraine conflict exploded.

Productivity growth was very low and employment growth was slowing. Capitalist production and investment slowed because the profitability of capital in the major economies had reached near historic lows before the pandemic. The recovery in investment and production after COVID was just a ‘sugar rush’ as economies re-opened and pent-up spending was released. Now it’s becoming clear that output and investment growth in the major economies is just too weak to respond to the revived demand. So inflation has rocketed.

What this tells us is that it is not excessive demand or wage-cost push, or for that matter too much money, that is causing accelerating inflation but instead weak production growth and insufficient investment in productive assets. There is no ‘excessive demand’ from US households. Real retail sales growth (ie after taking into account inflation) is flat.

And we already know that wages are not keeping pace with inflation rates in all the major economies.

Now there are the first signs that even the so-called strong employment market is weakening in the US. Unemployment benefit claims are now on the rise.

So central bask hikes will not bring inflation under control – unless a slump or recession ensues. The policy of aggressive interest rate hikes in the late 1970s by the then Fed chair Paul Volcker is often cited as proof that central banks can deliver lower inflation. The reality was that Volcker’s hikes only contributed to delivering one of the most severe slumps (1980-82) in the second half of the 2oth century that eventually decimated the manufacturing sectors of the major advanced economies. It was the recession, slumping production and rising unemployment that eventually led to the reduction in inflation.

That is the prospect now if the Fed adopts even half the policy hikes that Volcker applied. The profitability of capital was already low and now falling again in the major economies, as I have shown in previous posts. And as I argued in a previous post, alongside that fall is the issue of the cost of debt

Already investors have yanked billions of dollars out of corporate bonds because they fear that corporate busts are soon to emerge.

A recent analysis by the FT, found that companies with ‘volatile earnings and high interest costs’ face increasing risk of going bust. These ‘zombie companies’ as they often called, will reach 20% of all companies if interest rates double (which is the target of many central banks) and if profits fall by 25%, which now seems very likely.

And of course, that also applies to what is called ‘emerging market debt’ owed by many poor countries around the world. More than $38bn has flowed out of specialist mutual and exchange traded bond funds since the start of the year, according to EPFR data. The exodus will continue.

The world of credit is tightening and bringing with it a downturn in financial asset prices, but also exposing the fault-lines in ‘real economy’ production. As the FT put it in an editorial this week:“ the choice is stagflation, or deflationary depression.”

No comments:

Post a Comment