At the beginning of each year, I make an attempt to forecast what will happen in the world economy for the year ahead. The point of making any forecast at all is often ridiculed. After all, surely there are just too many factors to feed into any economic forecast to get even close to what eventually happens. Moreover, mainstream economic forecasts have been notable in their failure. In particular, they never forecast a slump in production and investment even a year ahead. In my view, that shows an ideological commitment to the promotion of the capitalist mode of production. Although, it is a confirmed feature of capitalism that there are regular and recurring slumps in production, investment and employment, these slumps are never forecast by the mainstream or official agencies until they have happened.

That does not mean making a forecast is a waste of time, in my view. In scientific analysis, theory must have predictive power and that applies as well to economics if it is to be considered a science and not just an apology for capitalism. So if Marx’s theory of crises is to be validated, it must have some predictive power – namely that slumps in capitalist production will happen at regular recurring intervals, primarily due to changes in the rate of profit on capital and resulting movements in the mass of profits in a capitalist economy.

But as I have argued in previous posts, predictions and forecasts are different. From their models, climate scientists predict a dangerous rise in global temperatures; and virologists have also been predicting an increase in deadly pathogens reaching humans in a series of pandemics. But forecasting when exactly these predictions become reality is much more difficult. On the other hand, climatologists are not yet able to forecast well what the weather in a country is likely to be over a whole year, but their models are now pretty accurate for the weather over the next three days. So forecasts for output, investment, prices and employment one year ahead are not so impossible.

Anyway, let’s bite the bullet and make some forecasts for 2022. Last year’s forecast was relatively easy. It was clear that all the major economies were going to make a recovery from the slump of 2020. I wrote: “Real GDPs will grow, unemployment rates will start to decline and consumer spending will pick up.” With the rollout of vaccines, the “G7 economies should be recovering significantly by mid-year”. But I added that “this will be no V-shaped recovery, which means a return to previous levels of national output, employment and investment. By the end of 2021, most major economies (China excepted) will still have levels of output etc below that at the beginning of 2020.” These forecasts have been borne out.

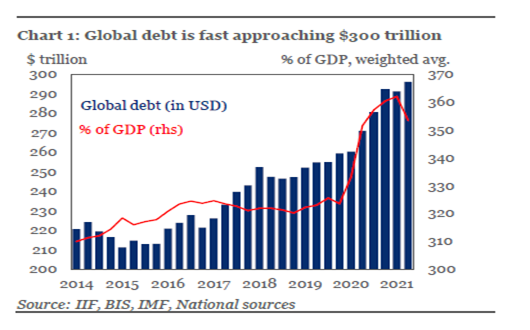

There were two main reasons why I expected the economic recovery would not restore global output to 2019 levels by the end of 2021. First, there had been a significant ‘scarring’ of the major economies from the COVID pandemic in jobs, investment and productivity of labour that can never be recovered. This was exhibited in a huge rise in debt, both public sector and private, that weighs down on the major economies like the permanent damage of ‘long COVID’ on millions of people.

This ‘scarring’ was also exhibited in a fall in average profitability of capital in the major economies in 2020 to a new low, the revival of which in 2021 was not sufficient to restore profitability even to the level of 2019.

Nevertheless, as expected, global real GDP growth in 2021 was probably around 5%, after falling an unprecedented 3.5% in the 2020 slump. According to the IMF, in the advanced capitalist economies, real GDP per person fell 4.9% in 2020 but rose 5.0% in 2021. That meant real GDP per person in these economies was still slightly below the level reached at end-2019. So two years of scarring.

Most forecasts for this year, 2022, are more (or less) of the same as in 2021. The world economy is expected to grow around 3.5-4.0% in real terms – a significant slowing compared to 2021 (down 25% on the rate). Moreover, the advanced capitalist economies are forecast to grow at less than 4% in 2022 and at less than 2.5% in 2023.

Forecast for real GDP growth (%) by the Conference Board.

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| US | -3.4 | 5.7 | 3.8 | 3.0 |

| Europe | -6.6 | 5.0 | 4.1 | 1.7 |

| Japan | -4.7 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 1.4 |

| ACE | -4.6 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 2.3 |

| China | 2.2 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 3.2 |

| India | -7.1 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 4.3 |

| LA | -7.5 | 6.4 | 2.2 | 1.7 |

| EME | -2.1 | 5.2 | 4.0 | 3.2 |

| World | -3.3 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 2.8 |

It’s a similar story for the so-called emerging economies of the ‘Global South’, including China and India. China was the only major economy that avoided a slump in the year of COVID, 2020. But growth of China’s output in 2021 was much weaker than after the end of the Great Recession in 2009. The Conference Board seriously underestimates China’s growth rates, but even so, in 2022 China’s real GDP is unlikely to rise much above 5%.

What these forecasts suggest is that the ‘sugar-rush’ of pent-up consumer spending engendered by COVID cash subsidies from fiscal spending by governments and huge injections of credit money by central is waning and will do so further this year. Indeed, as we know, central banks are now planning to ‘taper off’ their credit creation and even raise policy interest rates on borrowing. The Bank of England has already started to hike its policy rate and the US fed plans three hikes in the latter part of 2022.

And all the forecasts for this year rely on the view that the new Omicron variant of COVID will prove to be short-lived and only mildly damaging to human health, thanks to vaccinations and new medical treatments. That may be optimistic and even if Omicron turns out not to disrupt economies this year, there is no certainty that another, more devastating variant may not emerge.

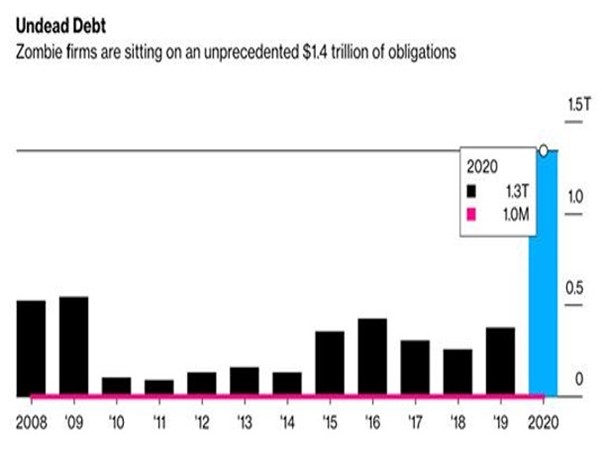

Then, in my view, there is a third leg in the aftermath of COVID slump to come, probably in 2022. In my 2021 forecast, I raised the possibility that such was the size of corporate debt and the large number of so-called ‘zombie companies’ that were not even making enough profit to cover the servicing of their debts (despite very low interest rates), that a financial crash could ensue.

And that is just the risk in the advanced capitalist economies. The so-called emerging economies are already in a dire state. According to the IMF, about half of Low Income Economies (LIEs) are now in danger of debt default. ‘Emerging market’ debt to GDP has increased from 40% to 60% in this crisis. And there is little room to boost government spending to alleviate the hit.

The ‘developing’ countries are in a much weaker position compared with the global financial crisis of 2008-09. In 2007, 40 emerging market and middle-income countries had a combined central government fiscal surplus equal to 0.3 per cent of gross domestic product, according to the IMF. Last year, they posted a fiscal deficit of 4.9 per cent of GDP. The government deficit of ‘EMs’ in Asia went from 0.7 per cent of GDP in 2007 to 5.8 per cent in 2019; in Latin America, it rose from 1.2 per cent of GDP to 4.9 per cent; and European EMs went from a surplus of 1.9 per cent of GDP to a deficit of 1 per cent. The Conference Board is forecasting a fall in the real GDP growth rate for Latin America of two-thirds from 6.4% to 2.2% and then even lower in 2023. That’s a recipe for a serious debt and currency crisis in these countries in 2022 – already Argentina is heading for another default on its debt.

Emerging economy governments are thus faced with either applying severe fiscal austerity that would prolong their stagnation; or devaluing their currencies to try and boost export growth. The Turkish government of Erdogan has opted for the policy of cutting not raising interest rates – in the policy style of Modern Monetary Theory. This has led to an outflow of capital and a 40% depreciation of the Turkish lira against major currencies. Inflation has rocketed. In 2022, the Turkish economy will dive and ‘stagflation’ will ensue.

A financial and debt crisis did not happen in 2021. On the contrary, global stock and bond markets never had it so good. Central bank-financed credit flooded into financial assets like there was no tomorrow. The result has been a staggering rise in financial asset prices (stocks and bonds) and in real estate. Central banks have injected $32 trillion into financial markets since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, lifting global stock market capitalisation by $60 trillion. And companies worldwide raised $12.1 trillion by selling stock and taking out loans as a result. The US stock market index rose 17% in 2021, repeating a similar rise in 2020. The S&P 500 index reached a record high. The Nikkei 225 Index its highest annual gains since 1989.

But as we go into 2022, the days of ‘easy money’ and cheap loans are coming to an end. The huge stock market boom of the last two years looks likely to peter out. Indeed, since April 2021, just five high-tech stocks—Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Tesla and the Google parent Alphabet—have accounted for more than half of the rise in US S&P index, while 210 stocks are 10% below their 52-week highs. And one-third of ‘leveraged loans’, a popular form of debt creation, in the US have a debt to earnings ratio exceeding six, a level regarded as dangerous to financial stability.

So this year could be the one for a financial crash or at least a severe correction in stock market and bond prices, as interest rates rise, eventually driving a layer of zombie corporations into bankruptcy. This is what central banks fear. That is why most are being very cautious about ending the era of easy money. And yet they are being driven to do so because of the sharp rise in the inflation rates of prices of goods and services in many major economies.

US consumer goods and services annual inflation rate (%)

This inflation spike is mainly due to pent-up consumer demand as people run down savings built up during lockdowns coming up against supply ‘bottlenecks’. These bottlenecks are the result of the restrictions on the international transport of goods and components and continued restrictions on raw materials and components for production – it is part of the aftermath of the COVID slump of 2020 and because much of the world is still suffering from the pandemic.

Mainstream economics is divided over whether this spike in inflation is ‘transitory’ and inflation rate will return to ‘normal’ levels or not. In my view, the current high inflation rates are likely to be ‘transitory’ because during 2022 growth in output, investment and productivity will probably start to drop back to ‘long depression’ rates. That will mean that inflation will also subside, although still be higher than pre-pandemic.

There is a view that 2022 will actually be the start of new levels of GDP and productivity growth as experienced by the US in the ‘roaring twenties’ of the last century after the end of the Spanish flu epidemic. During the so-called roaring twenties, US real GDP rose 42% and by 2.7% a year per capita. But there seems to be no evidence to justify the claim by some mainstream optimists that the advanced capitalist world is about to experience a roaring 2020s. The big difference between the 1920s and the 2020s is that the 1920-21 slump in the US and Europe cleared out the ‘deadwood’ of inefficient and unprofitable companies so that the strong survivors could benefit from more market share. Profitability of capital rose sharply in most economies. Nothing like that is being forecast for 2022 or beyond, as the Conference Board forecasts (above) show, or for that matter, those of the IMF (below).

Optimists for a new long boom in the 2020s to replace the long depression of the 2010s, like the Conference Board, base their argument on a revival of total factor productivity (TFP). This measure supposedly captures the role of efficiency and innovation in output growth. The CB reckons global TFP will rise by 0.4% on average annually this decade compared to zero over the past 20 years. That’s not much of an improvement when compared with the forecast slowing or even falling working-age employment and weak capital investment growth globally. Indeed, in Q3 2021, US productivity growth slumped on the quarter by the most in 60 years, while the year-on-year rate dropped 0.6%, the largest decline since 1993, as employment rose faster than output.

A long boom would only be possible, according to Marx, if there is a significant destruction of capital values in a major slump. By cleansing the accumulation process of obsolete technology and failing and unprofitable capital, innovation from new firms could then prosper. That’s because such ‘creative destruction’ would deliver a higher rate of profitability. But there is no sign yet of any sharp recovery in the average profitability of capital. Probably there needs to be a sustained rise of about 30% in profitability to deliver a new long boom like the ‘roaring twenties’ or the post-war ‘golden age’ or even that modestly achieved in the neo-liberal period of the late 20th century.

And don’t expect any further fiscal and monetary help from governments. Given the high level of public sector debt, pro-business governments everywhere are looking to reduce fiscal spending and budget deficits. Indeed, taxes are set to rise and government spending to be curtailed. According to the IMF, general government spending in 2022 will fall 8% as a share of GDP this year over last year. This fall is partly due to less spending on COVID support and a rise in GDP.

But if we look at the US government spending and revenue projections, according to the Congressional Budget Office, federal government spending is set to decline by 7% on average up to 2026 compared with 2021 levels while tax revenues are expected to rise by 25%. The US budget will be halved in 2022 and kept down for the following years. So no Keynesian-style fiscal stimulus is planned – on the contrary.

US president Biden’s plans to expand fiscal spending have been stymied by Congress and anyway would have had only a small impact on economic activity. The EU’s recovery fund for the weaker Eurozone economies has not yet even started and again will be insufficient to sustain faster economic growth.

In conclusion, assuming no new disasters from the continuing COVID pandemic, the world economy will grow in 2022, but nowhere near as fast as in the ‘sugar-rush’ year of 2021. And by the end of this year, most major economies will have started to slip back towards the low growth, poor productivity trends of the Long Depression of 2010s, with prospects of even slower growth over the rest of the decade.

No comments:

Post a Comment