|

| Faiza Factory Leicester. Working During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Source |

Leicester is a medium-sized city in the centre of England. It has come into the limelight in the last few weeks because of an outbreak of COVID-19 in the city, forcing a local lockdown, while the rest of England starts to ‘come out’. Leicester has a relatively high British Asian community and many are concentrated for work in the garment industry. And it is here that the COVID outbreak seems to have emerged.

The reason is clear. Garment workers in Leicester work out of tiny, unsafe factories or even homes, employed for below poverty wages ($5 an hour!) and they have worked throughout the coronavirus crisis lockdown. These small businesses had to carry on because there was really only one buyer, the online retailer, British Asian owned BooHoo. Like Amazon, Boohoo has made a fortune during the pandemic with shop-based retailers in lockdown. Its profits are registered in the tax haven island of Jersey. And it dominates the Leicester garment industry. It’s a classic example of monopsony power.

We often see the concept of ‘monopoly’ in political economy and leftist circles as a relevant category for modern capitalism. We don’t usually recognise ‘monopsony capitalism’. But we should. This is where Ashok Kumar’s book, Monopsony Capitalism Power and Production in the Twilight of the Sweatshop Age fills a gap.

Whereas, monopoly implies a dominant or hegemonic seller in the market for goods and services, controlling prices and keeping out potential rivals, monopsony implies the control of the market by a dominant buyer over many smaller sellers. The capitalist labour market is one key example, where capital exerts relative monopsonic power over workers, unless they are organised in unions etc.

The Boohoo monopsony in Leicester is repeated on an even larger scale with major retailers like Walmart in the US or Amazon globally, or manufacturers like Nike or Apple or food producers like Nescafe or Del Mar, which exert huge monopsonic power over their suppliers (in farming, garment and footwear, electronics etc).

Kumar is a lecturer in International Political Economy at the School of Business, Economics and Informatics at Birkbeck University. His book takes us to the heart of the monopsonic capitalism globally through the value chain of cheap garments and shoes in the shops of the ‘global north’ to the sweatshops of Bangladesh and other countries under the domination of the multi-nationals.

Monopsony Capitalism argues that the garment value chain globally relies on the unequal power dynamic of many suppliers and few buyers – monopsony. The result is a low level of surplus value capture at the production phase of the supply chain, which ensures chronically low capital investment in the peripheral countries’ industry. Cheap labour and many suppliers are preserved, as opposed to the use of machinery and fewer, larger companies. Fragmentation and low capital investment in garment and footwear value chains creates low barriers to entry, resulting in bidding wars between thousands of smaller firms from around the world. Indeed, a ‘sweatshop’ can be defined as a workplace where labour has essentially no bargaining power.

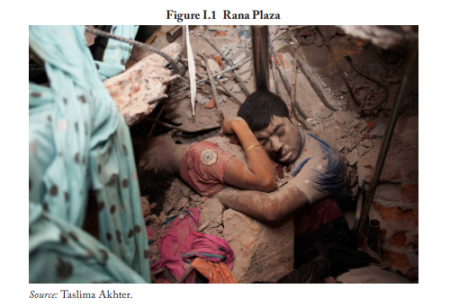

The Rana Plaza tragedy of 2013 when a massive garment factory in Bangladesh collapsed, floor upon floor, crushing many of its occupants was a catalytic moment. “The Rana Plaza disaster proved a monument to the complete and utter failure of Western activism: 1,134 workers perished.” Consumer boycotts and campaigning in the global North against ‘sweatshops’ proved to have had no effect.

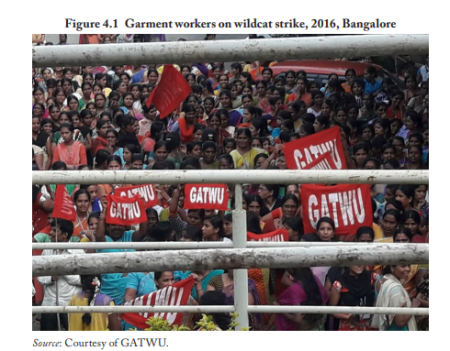

But what has happened since shows another way out of this nightmare. After Rana Plaza, the Bangladeshi unions demanded new safety conditions, similar to the way in which reduced hours and better safety was fought for in cotton sweatshops of mid-19th century Britain that Marx records. By August 2013, 45 garment factory unions had been registered with the Bangladeshi government. The unions used a ‘hot shop’ organizing model, following the trail of labour unrest from case to case, factory to factory, establishing and strengthening union footholds. An almost endless pool of small garment firms across the globe began to steadily disappear, absorbed into larger rivals or forced to merge. Thus, Kumar argues the monopsony power of the multi-national retailers increasingly faced oligopolistic companies, driven by their workforces to demand better prices and terms.

Kumar’s book analyses workers’ collective action at various sites of production primarily in China, India, Honduras, and United States, and secondarily in Vietnam, Cambodia, Bangladesh, and Indonesia. Action by labour in these countries have “tested the limits of the social order, stretching it until the seams show, and forcing bosses to come to the proverbial table, hat in hand, to hash out agreements with those who assemble their goods.”

In these case studies Kumar reveals that there has been increasing supplier-end consolidation, raising the surviving suppliers’ share of value, and so facilitating self-investment and higher entry barriers. Workers struggles over wages and conditions have altered the balance of economic power between the multi-nationals and the domestic suppliers.

Kumar reminds us that Marx and Engels argued that global capital would generate a global proletariat that would ultimately be its undoing. But perhaps collective worker action is the exception under capitalism. Maybe capital’s structural advantages in certain sectors, like garment and footwear, have effectively resolved the dialectical struggle in favour of capitalists. Kumar’s case studies suggest otherwise. The garment sector (and vertically disintegrated value chains generally) are also “animated by the logic of competition, which moves inexorably in the direction of consolidation, thereby reducing the monopsonistic power of buyers. while changes in the value chain are reflected in the bargaining power of workers.”

Kumar confirms that Marx’s law of accumulation still operates, namely that capitalism must increasingly come to rely on ‘dead labour’ (technology and so on) and less and less on ‘living labour’ (workers) and that includes the peripheral ‘emerging economies’ too. Higher levels of ‘dead labour’ start to create higher barriers to entry: Why? “Because the smaller the organic composition of capital, the less capital is required at the beginning in order to enter this branch and establish a new venture. It is far easier to put together the million or two million dollars necessary for building a new textile plant than to assemble the hundreds of millions needed to set up even relatively small steel works.”

Relying on this fundamental trend in capitalist accumulation, Kumar reckons “there is a change in the air.” In China, India, Honduras, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Indonesia many factories already have a relatively high organic composition. It becomes “possible to glimpse another world where bosses come to the proverbial table, hat in hand, to hash out agreements with those who assemble their goods. When labour unions, activists, and advocates marshal their resource – financial, moral, political, and human – to support smart, focused, bottom-up organizing in large, increasingly integrated firms, garment workers will transform their industry.”

Once barriers to entry have been established among the domestic suppliers it will be impossible to tear them down and return to monopsony power. Sweatshops occur where surpluses are limited, and production is diffuse and isolated from consumption. But competition eventually creates a centralized industry, with a few mega-firms in a few locations. Then suppliers ascend, giving workers the high ground too. But as Kumar says, “whether this is indeed the twilight of the sweatshop age or a new race to the bottom may ultimately depend on the self-organization and demands of the working people.”

That applies to the garment sweatshops of COVID-19 Leicester too.

No comments:

Post a Comment