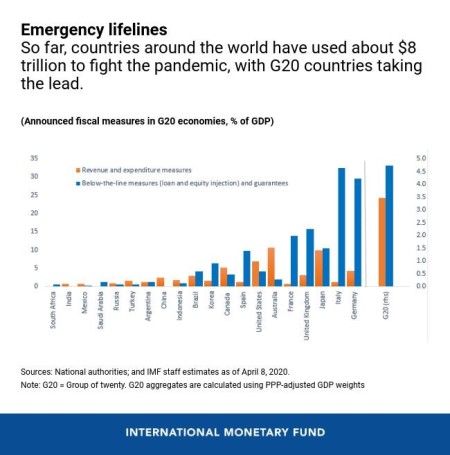

Globally, the IMF forecasts that general government budget deficits (ie where tax revenues fall short of government spending) will reach 10% of GDP in 2020, up from 3.7% in 2019. In the advanced capitalist economies, the deficit will be 10.7%, more than three times larger than in 2019. The US government will have a 15.4% of GDP deficit.

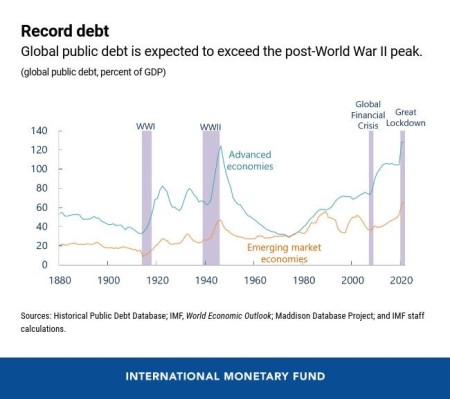

As a result, public sector debt levels are expected to exceed anything reached in the last 150 years – including after WW1 and WW2. The public sector debt ratio in 2020 will reach 122% of GDP in the advanced capitalist economies and 62% in the so-called emerging economies.

Everybody, whether governments, investors or economists, agree that there was no alternative but to expand public spending during the Great Lockdown to avoid or ameliorate the catastrophe of the global economy coming to a total halt. But as the lockdowns end (whether the pandemic is over or not), the question is whether this increased government spending can be allowed to continue and whether public sector debt levels must eventually be curbed and reduced.

After the end of the Great Recession, the predominant view among governments and economists alike was that public debt levels were too high and would damage economic growth rates and/or even engender a further financial crisis. Top economists like Rogoff and Reinhart argued that there was empirical evidence over centuries that showed when public debt ratios were above 90% of GDP, the probability of a financial crash was very high. This evidence was disputed at the time, but even so, it was generally held that measures to control public spending and raise taxes so that budget deficits were reduced and even eliminated to bring debt levels down were necessary to ensure future sustainable economic growth. This ‘Austerian’ view dominated and the apparently alternative Keynesian view that in a slump ‘deficits and debt don’t matter’ was rejected, sometimes even by Keynesians. When the Greek government faced disaster during the euro debt crisis of 2012-15, the powers that be were merciless in their view that there was no alternative.

But this time round, at least, things are different. Governments, on the whole, do not talk about getting public sector finances ‘under control’ and economists on the whole seem comfortable with governments running deficits far into the future even if it means rising public sector debt levels.

As former Goldman Sachs chief economist, and hedge fund manager Gavyn Davies recently put it: “Even more notable has been the unanimity among macroeconomists that massive fiscal and monetary stimulus is the appropriate response to a “wartime” economic emergency. Almost no one seriously disputes that policy should be doing “whatever it takes” to overcome the shock from the virus. This agreement reflects a key conclusion from public finance theory: that higher government debt is the correct shock absorber for the private sector in the face of unpredictable, temporary economic crises. It avoids the distortions that would follow the big variations in marginal tax rates that would otherwise be needed to finance a surge in public spending over a short period.” So the public sector is there to bail out the private (capitalist) sector when it goes into ‘unpredictable, temporary crisis’.

Davies goes on: “Most New Keynesian economists, including Paul Krugman and Lawrence Summers, believe high debt levels will not in themselves be a problem for advanced economies. They even suggest further rises in debt would be desirable, as that would help reverse the trend towards secular stagnation in Europe and the US.” A key reason for their optimism is that the annual cost of servicing the debt will be below the nominal growth rate in the economy and the central banks seem set to keep it there.

Indeed, central bank rates are near zero or even below and longer-term bond yields are at historic lows. So, if the interest cost of the government debt keeps below the growth rate, the debt/gross domestic product ratio will eventually stabilise. And as economic growth picks up, tax revenues will come through, enabling the ‘primary balance’ (tax minus non-interest spending) to rise. Then central banks can gradually allow interest rates to rise towards more ‘normal levels’. And the debt could be managed without a crisis.

The more extreme Keynesian position that is now popular is that even managing debt levels does not matter. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) reckons that, as long as there is ‘slack’ in the capitalist economy ie. unemployment, governments can spend indefinitely and central banks can support them by ‘printing money’ without any risk of default or financial collapse.

However, it may not be as simple as that. Calculating whether debt service is sustainable involves several key numbers: 1) the level of debt, 2) average interest rate on the debt, 3) fiscal deficit (which adds to the debt), 4) the size and growth of public expenditure, and 5) expansion rate of the economy. Sustainability of public debt service then depends on two numbers, the fiscal deficit and the initial size of the public debt.

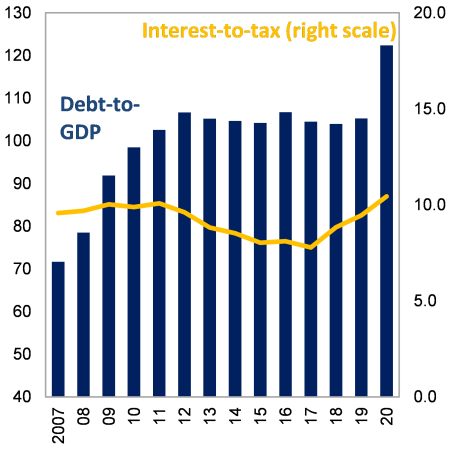

If government spending outside covering interest costs on existing debt continues to rise faster than tax revenues, then this ‘primary deficit’ will continually add to total public debt. This means that the interest cost of that debt will rise even if the rate of interest is very low. Already, the interest cost in government budgets in the major economies has reached 10% of tax revenues, even though interest rates have fallen. This cost is gradually eating into current spending on welfare, public sector investments and public services.

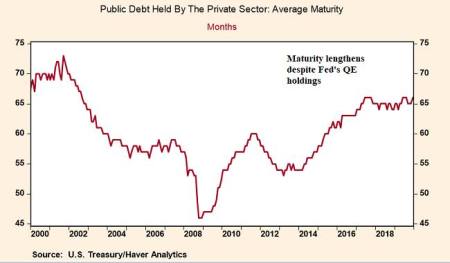

In the advanced economies, the maturity of public debt (the period before repayment of bonds is required) is about 7 years on average (it’s way higher in the UK). The longer the maturity, the less the impact of increased deficits and debt on debt servicing.

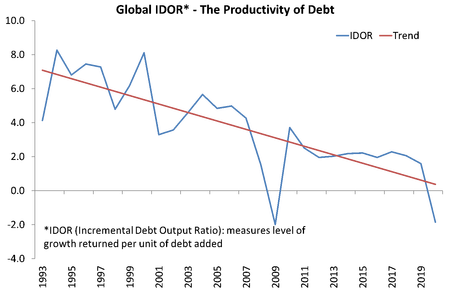

So it’s the growth constraint that is the main factor making public sector debt levels matter. ‘Excessive debt’ means government debt that is so high that it eats into corporate profitability through higher taxes on business, less subsidies to business, higher inflation costs and higher interest rates for borrowing across the board. So government spending, Keynesian-style, can only be a substitute for failing private investment and consumption for a short while. Ultimately, it is a burden on capitalism, not its saviour. That is why it must be reduced. If profitability of the capitalist sector remains low, and in the G7 average profitability on capital is at an all-time low, then investment and GDP growth will be weak. And the ‘productivity of debt’ will continue to fall.

Governments could just print money to pay for their debts (they have that unique power as MMT argues), but that would eventually mean devaluing the currency used to pay for things. It is something that the US has found with its external deficits. As a result, the buying value of the dollar has fallen over the last 30 years by over 25%.

Similarly, if governments print money to pay for their debts at home, they will eventually drive up inflation and devalue wages and savings. The ‘evil’ of inflation is even admitted by MMT, if only when full employment is reached and the ‘slack’ in the economy disappears. Governments can borrow and central banks can print money to finance the present public expenditures. However, these also involve taking on future risks. As Stephanie Kelton put it in her new book, The Deficit Myth: “Can we just print our way to prosperity? Absolutely not! MMT is not a free lunch. There are very real limits, and failing to identify—and respect—those limits could bring great harm. MMT is about distinguishing the real limits from the self-imposed constraints that we have the power to change.”(Kelton 2020, p. 37).

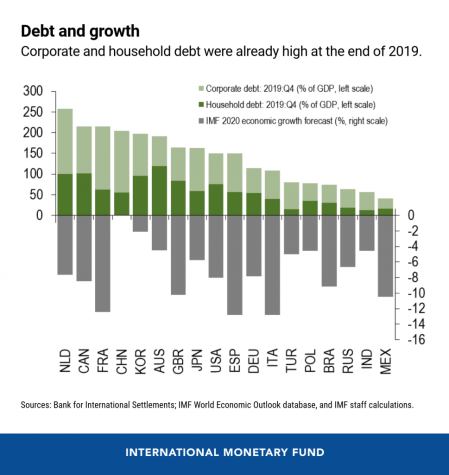

But the issue of debt, post-COVID is not only, or even mainly, about public debt; it is corporate debt that really matters. The pandemic slump began with a ‘supply shock’ as major sectors of the economy were locked down; then it became a ‘demand shock’ as households stopped spending and companies stopped investing; but a third leg of the crisis impends: a financial shock.

Corporate debt levels globally were already at record highs before the pandemic crisis.

Corporate sector ‘delinquencies’ (failing to meet debt repayments on time) and bankruptcies are rising. A whole layer of ‘zombie companies’ (where debt interest is not covered by profits) that this blog has talked about before on several occasions are likely to go bust before ‘normality’ is restored. And if there is any rise in interest rates, that trickle could turn into a flood and then an avalanche that takes down others and the banking system.

The amount of debt classified as distressed in the U.S. has surged 161% in just the last two months to more than half a trillion dollars. In April, corporate borrowers defaulted on $35.7 billion of bonds and loans, the fifth-largest monthly volume on record, according JPMorgan Chase & Co. And so far in 2020, the pace of corporate bankruptcy filings in the U.S. has already surpassed every year since 2009, the aftermath of the global financial crisis, Bloomberg data show.

So the levels of both public and corporate sector debt do matter. If governments go on raising public spending and budget deficits, it will squeeze the capitalist sector by sucking up all the demand for debt, while increasing the share of unproductive expenditure at the expense of public services and investment. If governments fund such spending through central bank ‘monetary financing’, the risk of inflation will return.

Why? The Japanese government has run permanent budget deficits since the 1990s and the government debt ratio will be over 250% of GDP this year. The Bank of Japan owns most of the new government debt outstanding, assets equivalent to 75% of GDP. But Japan has no inflation in the prices of goods and services. If anything, there is deflation. So why should budget deficits and rising debt lead to inflation?

The causes of inflation require a whole book on their own. The traditional mainstream theories fall into two categories: a monetary theory; changes in the quantity of money relative to output sets the rate of inflation; or that inflation of prices is caused by changes in the cost of production (wages, raw materials, oil prices etc). Neither of these is convincing as a theory (a future post here).

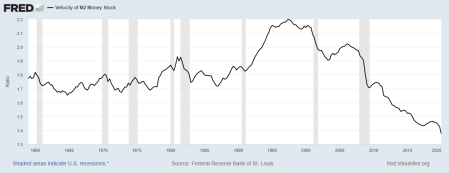

There is a massive rise in the quantity of money in economies, at the moment: money supply as represented by deposits in banks (M2) is up 25% yoy. But prices of goods and services are hardly rising – indeed, by year-end the consumer inflation rate in the US could be negative for the first time since the Great Recession and possibly down by the largest annual reduction since 1955.

The reason is obvious: consumer spending and capitalist investment is down hugely. Much of the money and government handouts is not going into spending or investment but into paying down debts or hoarding by companies. This is what happened in Japan. Indeed, what we find is that there has been a significant decline in the velocity of money since the early 2000s. The velocity of money measures the stock of money relative to nominal GDP – and it’s been falling. This is a good measure of hoarding money.

The trend matches the downturn in the rate of profit of capital and consumer price inflation. As profitability of investing in productive assets fell, investment growth slowed. Companies instead invested in financial assets (fictitious capital) or hoarded cash (the large companies). Interest rates and inflation fell, while stock markets boomed. And this is what is happening now. Inflation is non-existent because new value is not being created and so profits and wages are falling even faster than money supply can be injected.

However, that situation will change when the lockdowns ease over the next year (whatever the virus does). Then profits and wages will rise (not to the same levels as before, but still up). If central banks pump in yet more money and credit, then prices will rise because economic growth will remain weak. Demand (money) will exceed supply (new value). The hoarding effect will dissipate and prices will jump.

One estimate for inflation based on the mainstream quantity theory of money suggests inflation rates could jump to 4-6% if central banks go on printing money. My own estimate would suggest inflation would be around 3-4% next year (unpublished research). Inflation is bad news for labour because it will eat into real incomes, already stunned by the slump. It’s good news for companies as they try to hike prices to restore profits, but it’s bad news for the financial sector and bond investors as their real gains will be reduced.

Next year, the weight of both public and corporate debt will press down on economic recovery, while inflation will rise, putting upward pressure on interest rates. That’s a recipe for corporate bankruptcies and a financial crisis, alongside ‘stagflating’ economies, similar to the 1970s.

1 comment:

Great read! Thank you!

Post a Comment