At the recent ASSA 2020 conference there was a session on whether Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the ubiquitous measure of national output, was adequate as a gauge of “well-being or social welfare”. Various proposals have been put forward for attempting to measure social welfare, including “dashboards” of economic and social indicators as well as approaches that are more explicitly tied to economic theory. The US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) initiated a discussion at ASSA to consider the pros and cons of alternative approaches.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the basic mainstream measure of a country’s level of output and even prosperity. It is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced in a specific time period. The measure goes back to the earliest of days of classical political economy, with William Petty developing the basic concept in the 17th century. The modern concept was first developed by Simon Kuznets in 1934 to measure the national output of the US.

There are three ways to measure GDP. The first is the production approach, which sums up the outputs of every enterprise. The second is the expenditure approach which sums up all the purchases made; and third is the income approach which sums up all the incomes received by producers.

These three different approaches broadly match the three main schools of economic thought. The production approach has an affinity with neoclassical school, which sees national output as the sum of all micro-agents’ production. The expenditure approach has been adopted by the Keynesian school, which looks at investment, consumption and saving at a ‘macro level’ to measure “effective demand”. The income approach has the closest connection with Marxist and classical political economy, because it distinguishes wages and profits as the main categories of national income and thus exposes the class divisions in the distribution of GDP; and the driving force for investment and production in capitalism ie profit.

Ever since the development of GDP, multiple observers have pointed out limitations of using GDP as the overarching measure of economic and social progress. GDP does not account for the distribution of income among the residents of a country, because GDP is merely an aggregate measure. Neither does it measure unpaid housework, the level of happiness or well-being. That is why there have been various attempts to replace GDP with other ‘broader’ measures.

One recent attack on GDP as a measure of national ‘wealth’ or well-being has come from Vint Cerf via this Wired article. Cerf makes the usual complaint that “the measure does not capture the level of pro bono work that pervades many societies, by homemakers whose unpaid labour is an integral part of most functional societies, and non-profit organisations whose work also contributes to the benefit of society.” He goes on “Moreover, GDP does not capture the many negative effects of some economic activities such as pollution, including carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Their consequences should be factored into any measure of economic well-being if we are to accurately assess the state of the planet and its population.” And finally,“As an average measure, GDP also fails to capture wealth and income disparities within a society, often negatively correlated with the health of that society.”

All this is true. But is that the purpose of GDP as a measure? At the time of its launch, Kuznets specifically warned against considering GDP as a measure of ‘welfare’ in a society. Vint’s critique, echoed by others, fails to recognise that the value (or wealth) that modern economics wants to measure is the ‘market value’ of national output not the welfare of labour, women and children. Capitalism has no direct interest in measuring that. GDP has a specific purpose for capital not labour.

Household work provides a massive contribution to the welfare of communities. And it delivers unpaid labour to sustain labour power in work for capitalist enterprises. But because it is not a cost for capital, it does not need to be included in GDP. Similarly, the grotesque (and rising) inequalities of income and wealth that exist within most countries is not a relevant factor for capitalist investment and production and so again does not need to be included in GDP. Finally, the ‘externalities’ of capitalist production: eg, diseases, industrial accidents, pollution and climate change are not immediate costs to the profitability of capital (private ownership of production). Indeed, if these ingredients were included in a revised measure of national ‘value’ they would become confusing obstacles to measuring properly the ‘health’ of capitalist production in a country. And that is what matters in capitalism: having good measures of capitalist accumulation for policy decisions by capitalist enterprises and government and monetary authorities.

Of course, even within that paradigm, the GDP measure has its faults. Diane Coyle is one economist that has criticised strongly GDP as a sufficiently accurate measure of production and investment. She argues that GDP does not capture changes in investment that involve ‘intangibles’ and innovation. In other words, national output and productivity growth may be much higher than GDP exposes. However, even here, the argument that the failure to measure intangibles explains the productivity puzzle (low productivity growth) is not convincing.

Mariana Mazzucato got a lot of traction out of her recent book, The value of everything, where she complains that in GDP, finance is regarded as productive when it is really an ‘extractive’ sector and government investment is not given the ‘utility’ it deserves in GDP. But this is to misunderstand the law of value under capitalism. Under capitalism, production of commodities (things and services) are for sale to obtain profit. Commodities must have use value (be useful to someone), but they must also have exchange value (make a sale for profit). GDP is biased as a measure of value created in an economy for that good reason.

For Marxist analysis, there are many issues with using GDP. National output in Marxist terms is c+v+s. C is ‘constant capital’ (raw materials, intermediate products used up in production plus the depreciation of machinery etc). V is wages spent on the labour force + S (profits made on sales of the commodities produced). In theory, GDP data can be converted into these Marxist categories because in an economy total prices of all goods in aggregate must equal total values in labour time, even though that equality will not exist in sectors of the economy.

The practical complexities of turning GDP as measured by government statistics in national accounts into the Marxist formulae have been comprehensively explained in works like that of Shaikh and Tonak. But when it comes to the world economy and the transfer of value between countries and companies globally, GDP is inadequate and misleading. As John Smith has pointed out, “it is impossible to analyse the global economy without using data on GDP and trade, yet every time we uncritically cite this data we open the door to the core fallacies of neoclassical economics which these data project.” The key concept within GDP is ‘value added’ by ‘agents of production’, but that means GDP does not expose value that is transferred or redistributed between countries or companies as a result of competition in markets.

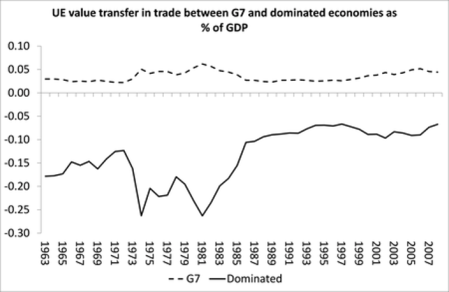

Just as more technologically advanced companies get a transfer of value from less advanced companies through competition on the market (Marx’s transformation of values into prices of production), so imperialist countries get a transfer of value from peripheral countries through the unequal exchange of value in international trade and through transfer pricing within companies. GDP does not capture that. However, recent Marxist research has made progress in measuring this transfer in the imperialist countries (see Carchedi and Roberts, Ricci and URPE_CHN_2019). These suggest that the GDP of the major capitalist economies is exaggerated by transfers of value through international trade and multi-national pricing equivalent to 3-5% of GDP every year.

Then there is the issue of productive and unproductive labour, something that Mazzucato took up but in a misleading way. Mazzucato argues that the government sector creates value, but that is because she considers only use-value and does not recognise the dual character of value under capitalism, where profit through exploitation is value. Marxist value theory maintains that many sectors and people are supposedly generating value-added but are really engaged in non-productive activities like finance and administration that produce no value at all. And for capital, that includes the government sector: it may be necessary, but it is not value-creating for capital.

As Marx put it: “Only the narrow-minded bourgeois, who regards the capitalist form of production as its absolute form, hence as the sole natural form of production, can confuse the question of what are productive labour and productive workers from the standpoint of capital with the question of what productive labour is in general, and can therefore be satisfied with the tautological answer that all that labour is productive which produces, which results in a product, or any kind of use value, which has any result at all.”

For the neoclassical theory, any labour whose outcome can secure remuneration in the market is considered productive and contributes to the creation of new value. Thus, not only activities in the sphere of commodity circulation, but also those aimed at maintaining and reproducing the social order, are considered to produce new values and increase the level of prosperity and wealth of an economy

In contrast, as Shaikh and Tonak explain: “Economists of the classical political economy tradition pay particular attention to the fact that the non-production sectors of trade and finance as well as government in order to perform their socially useful functions employ labour and other inputs while at the same time their capital stock depreciates; such expenses are drawn out from the surplus generated by the productive sectors of the economy.” (Shaikh and Tonak 1994, p61).

As Tsoulfidis and Tsaliki put it: “The main problem with orthodox national accounts is that they present many activities as ‘production’ while they should be portrayed as ‘social consumption’. As the ‘personal consumption’ sphere contributes to the reproduction of individuals in a capitalist society, the non-productive activities, such as trade, financial services or private security, in turn contribute to the reproduction and development of the capitalist system; however, their necessity does not negate the fact that as the total consumption (personal and social) increases, the part of surplus destined for the accumulation of capital is reduced and by extent the social wealth diminishes.”

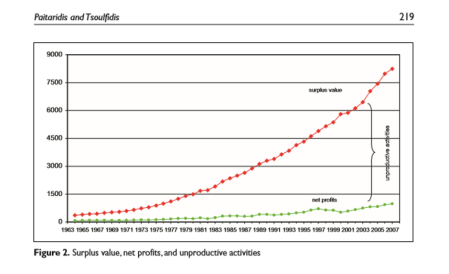

So measuring the relative expansion of productive and unproductive activities is crucial to gauging the growth potential of capitalist economy, because only investment in productive sectors can sustain expansion under capitalism. Indeed, a rising share of unproductive activity will exert a downward effect on the profitability of capital over time.

Again, this is an area where Marxist research has made strides in measurement: (Moseley; Roberts; Paitaridis, Tsoulfidis and Tsaliki, Peter Jones and others). In this way, we can obtain the value in GDP.

No comments:

Post a Comment