Financialisation, like neoliberalism, is the buzz word among leftists and heterodox economists. It dominates leftist academic conferences and circles as the theme that supposedly explains crises, as well as a cause of rising inequality in modern capitalist economies particularly over the last 40 years. The latest manifestation of this financialisation hypothesis comes from Grace Blakeley, a British leftist economist, who appears to be a rising media star in the UK. In a recent paper, she presented all the propositions of the financialisation school.

But what does the term ‘financialisation’ mean and does it add value to our understanding of the contradictions of modern capitalism and guide us to the right policy to change things? I don’t think so. This is because either the term is used so widely that it provides very little extra insight; or it is specified in such a way as to be both theoretically and empirically wrong.

The wide definition mainly quoted by the financialisation school was first offered by Gerald Epstein. Epstein’s definition was “financialization means the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies.” As you can see, this tells us little beyond the obvious that we can see in the development of modern, mature capitalism in the 20th century.

But as Epstein says: “some writers use the term ‘financialization’ to mean the ascendancy of ‘shareholder value’ as a mode of corporate governance; some use it to refer to the growing dominance of capital market financial systems over bank-based financial systems; some follow Hilferding’s lead and use the term ‘financialization’ to refer to the increasing political and economic power of a particular class grouping: the rentier class; for some financialization represents the explosion of financial trading with a myriad of new financial instruments; finally, for Krippner (who first used the term – MR) herself, the term refers to a ‘pattern of accumulation in which profit making occurs increasingly through financial channels rather than through trade and commodity production’”.

The content of financialisation under these terms takes us much further, especially the Krippner approach. The Krippner definition takes us beyond Marx’s accumulation theory and into new territory where profit can come from other sources than from the exploitation of labour. Finance is the new and dominant exploiter, not capital as such. Thus finance is now the real enemy, not capitalism as such. And the instability and speculative nature of finance capital is the real cause of crises in capitalism, not any fall in the profitability of production of things and services, as Marx’s law of profitability argues.

As Stavros Mavroudeas puts it in his excellent new paper (393982858-QMUL-2018-Financialisation-London), the ‘financialisation hypothesis’ reckons that “money capital becomes totally independent from productive capital (as it can directly exploit labour through usury) and it remoulds the other fractions of capital according to its prerogatives.” And if “financial profits are not a subdivision of surplus-value then…the theory of surplus-value is, at least, marginalized. Consequently, profitability (the main differentiae specificae of Marxist economic analysis vis-à-vis Neoclassical and Keynesian Economics) loses its centrality and interest is autonomised from it (i.e. from profit – MR).”

As Mavroudeas says, financialisation is really a post-Keynesian theme “based on a theory of classes inherited from Keynes that dichotomises capitalists in two separate classes: industrialists and financiers.” The post-Keynesians are supposedly ‘radical’ followers of Keynes from the tradition of Keynesian-Marxists Joan Robinson and Michel Kalecki, who reject Marx’s theory of value based on the exploitation of labour and the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. Instead, they have a distribution theory: crises are either the result of wages being too low (wage-led) or profits being too low (profit-led). Crises in the neoliberal period since the 1980s are ‘wage-led’. Increased (‘excessive’?) debt was a compensation mechanism to low wages, but only caused and exacerbated a financial crash later. Profitability had nothing to do with it.

As Mavroudeas explains, the hypothesis goes: “The advent of neoliberalism in the 1980s transformed radically capitalism. Liberalisation and particularly financial liberalization led to financialisation (as finance was both deregulated and globalized). This caused a tremendous increase in financial leverage and financial profits but at the expense of growing instability. This resulted in the 2008 crisis, which is a purely financial one.”

Linking debt to the post-Keynesian distribution theory of crises follows from the theories of Hyman Minsky, radical Keynesian economist of the 1980s, that the finance sector is inherently unstable because “the financial system necessary for capitalist vitality and vigor, which translates entrepreneurial animal spirits into effective demand investment, contains the potential for runaway expansion, powered by an investment boom.” The modern follower of Minsky,Steve Keen, puts it thus: “capitalism is inherently flawed, being prone to booms, crises and depressions. This instability, in my view, is due to characteristics that the financial system must possess if it is to be consistent with full-blown capitalism.” Blakeley too follows closely the Minsky-Kalecki analysis and offers it as an improvement on or a modern revision of Marx.

Many in the financialisation school go onto argue that ‘financialisation’ has created a new source of profit (secondary exploitation) that does not come from the exploitation of labour but from gouging money out workers and productive capitalists through financial commissions, fees, and interest charges (‘usury’). I have argued in many posts that this is not Marx’s view.

Post-Keynesian authors and supporters of financialisation like JW Mason refer to the work of mainstream economists like Mian and Siaf to support the idea that modern capitalist crises are the result of rising inequality, excessive household debt leading to financial instability and have nothing to do with the failure of profit ability in productive investment. Mian and Sufi published a book, called the House of Debt, described by the ‘official’ proponent of Keynesian policies, Larry Summers, as the best book this century! In it, the authors argue that “Recessions are not inevitable – they are not mysterious acts of nature that we must accept. Instead recessions are a product of a financial system that fosters too much household debt”.

For me, financialisation is a hypothesis that looks only at the surface phenomena of the financial crash and concludes that the Great Recession was the result of financial recklessness by unregulated banks or a ‘financial panic’. Marx recognised the role of credit and financial speculation. But for him, financial investment was a counteracting factor to the tendency for the rate of profit to fall in capitalist accumulation. Credit is necessary to lubricate the wheels of capitalist commerce, but when the returns from the exploitation of labour begin to drop off, credit turns into debt that cannot be repaid or at serviced. This is what the financialisation school cannot explain: why and when does credit turn into excessive debt?

UNCTAD is a UN research agency specialising in trade and investment trends. It published a report on the move from investment in productive to financial assets. It was written by leading post-Keynesian economists. It found that companies used more of their profits to buy shares or pay our dividends to shareholders and so less was available productive investment. But again, this does not tell us why this started to happen from the 1980s.

In the current issue of Real World Economics Review, an on-line journal dominated by post-Keynesian analysis and the ‘financialisation’ school, John Bolder considers the connection between the ‘productive and financial uses of credit’: “up until the early 1980s, credit was used mostly to finance production of goods and services. Growth in credit from 1945 to 1980 was closely linked with growth in incomes. The incomes that were generated were then used to amortize and eventually extinguish the debt. This represented a healthy use of debt; it increased incomes and introduced negligible financial fragility.” But from the 1980s, “credit creation shifted toward asset-based transactions (e.g., real estate, equities bonds, etc.). This transition was also fuelled by the record-high (double-digit) interest rates in the early 1980s and the relatively low risk-adjusted returns on productive capital”.

‘Financialisation’ could be the word to describe this development. But note that Bolder recognises that it was fall in profitability (‘low risk-adjusted returns on productive capital’) in productive investment and the rise in interest costs that led to the switch to what Marx would call investment in fictitious capital. But this does not mean that finance capital is now the decisive factor in crises or slumps. Nor does it mean the Great Recession was just a financial crisis or a ‘Minsky moment’ (to refer to Hyman Minsky’s thesis that crises are a result of ‘financial instability’ alone). Crises always appear as monetary panics or financial collapses, because capitalism is a monetary economy. But that is only a symptom of the underlying cause of crises, namely the failure to make enough money!

Guglielmo Carchedi, in his excellent, but often ignored Behind the Crisis states: “The basic point is that financial crises are caused by the shrinking productive base of the economy. A point is thus reached at which there has to be a sudden and massive deflation in the financial and speculative sectors. Even though it looks as though the crisis has been generated in these sectors, the ultimate cause resides in the productive sphere and the attendant falling rate of profit in this sphere.”

Despite the claims of the financialisation school, the empirical evidence is just not there. For example, Mian and Sufi reckon that the Great Recession was immediately caused by a collapse in consumption. This is the traditional Keynesian view. But the Great Recession and the subsequent weak recovery was not the result of consumption contracting, but investment slumping (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/11/30/us-its-investment-not-consumption/).

Recently Ben Bernanke, former head of the US Federal Reserve during the great credit boom of the early 2000s, has revived his version of ‘financialisation’ as the cause of crises. For him, crises are the result of ‘financial panics’ – ie people just lose their heads and panic into selling and calling in their credits in a completely unpredictable way (“Although the panic was certainly not an exogenous event, its timing and magnitude were largely unpredictable, the result of diverse structural and psychological factors”). In his latest revival, Bernanke considers empirically any connection between ‘financial variables’ like credit costs and ‘real economic activity’. He concludes that “the empirical portion of this paper has shown that the financial panic of 2007-2009, including the runs on wholesale funding and the retreat from securitized credit, was highly disruptive to the real economy and was probably the main reason that the recession was so unusually deep.”

But when we look at the evidence provided, Bernanke has to admit that “balance sheet factors (ie changes in debt etc) do not forecast economic developments well in my setup.” In other words, his conclusions are not supported by his own empirical results. “It may be that both household and bank balance sheets evolve too slowly and (comparatively) smoothly for their effects to be picked up in the type of analysis presented in this paper.”

And yet there is plenty of evidence for the Marxist view that it is a collapse in profitability and profits in the productive sectors that is the necessary basis for a slump in the ‘real’ economy. All the major crises in capitalism came after a fall in profitability (particularly in productive sectors) and then a collapse in profits (industrial profits in the 1870s and 1930s and financial profits at first in the Great Recession). Wages did not collapse in any of these slumps until they started.

In a chapter of our new book, World in Crisis, G Carchedi provides compelling empirical support for Marx’s law of profitability showing the link between the financial and productive sectors in capitalist crises. From the early 1980s, the strategists of capital tried to reverse the low profitability reached then. Profitability rose partly through a series of major slumps (1980, 1982, 1991, 2001 etc). But it also recovered (somewhat) through so-called neoliberal measures like privatisations, ending trade union rights, reductions in government and pensions etc.

But there was also another countertendency: the switch of capital into unproductive financial sectors. “Faced with falling profitability in the productive sphere, capital shifts from low profitability in the productive sectors to high profitability in the financial (i.e., unproductive) sectors. But profits in these sectors are fictitious; they exist only on the accounting books. They become real profits only when cashed in. When this happens, the profits available to the productive sectors shrink. The more capitals try to realize higher profit rates by moving to the unproductive sectors, the greater become the difficulties in the productive sectors. This countertendency—capital movement to the financial and speculative sectors and thus higher rates of profit in those sectors—cannot hold back the tendency, that is, the fall in the rate of profit in the productive sectors.”

Financial profits have claimed an increasing share of real profits throughout the whole post–World War II phase. “The growth of fictitious profits causes an explosive growth of global debt through the issuance of debt instruments (e.g., bonds) and of more debt instruments on the previous ones. The outcome is a mountain of interconnected debts. ….But debt implies repayment. When this cannot happen, financial crises ensue. This huge growth of debt in its different forms is the substratum of the speculative bubble and financial crises, including the next one. So this countertendency, too, can overcome the tendency only temporarily. The growth in the rate of profit due to fictitious profits meets its own limit: recurring financial crises, and the crises they catalyze in the productive sectors.”

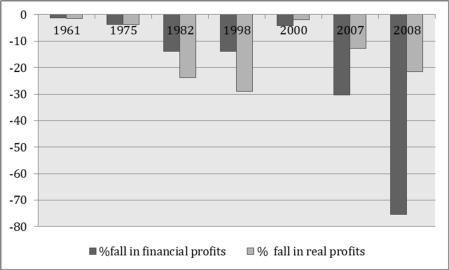

What Carchedi finds is that “Financial crises are due to the impossibility to repay debts, and they emerge when the percentage growth is falling both for financial and for real profits.“ Indeed, in 2000 and 2008, financial profits fall more than real profits for the first time.

Carchedi concludes that “It is held that if financial crises precede the economic crises, the former determine the latter, and vice versa. But this is not the point. The question is whether financial crises are preceded by a decline in the production of value and surplus value…The deterioration of the productive sector in pre-crisis years is thus the common cause of both financial and non-financial crises. If they have a common cause, it is immaterial whether one precedes the other or vice versa. The point is that the (deterioration of the) productive sector determines the (crises in the) financial sector.”

By rejecting Marx’s law of value and the law of profitability, the post-Keynesian ‘financialisation’ school opts for the idea that the distribution between profits and wages; rising inequality and debt; and above all, an inherent instability in finance that causes crises. Actually, it is ironic that these radical followers of Keynes look to the dominance of finance as the new form of (or stage in) capital accumulation because Keynes thought that capitalism would eventually evolve into a leisure society with the ‘euthanasia of the rentier’ ie the financier, would disappear. It was Marx who predicted the rise of finance alongside increasing centralisation and concentration of capital.

The rejection of changes in profits and profitability as the cause of crises in a profit-driven economy can only be ideological. It certainly leads to policy prescriptions that fall well short of replacing the capitalist mode of production. If you think finance capital is the problem and not capitalism, then your solutions will fall short.

In the Epstein book, various policy prescriptions for dealing with the evil of “excessive financialisation” are offered. Grabel (chapter 15) wants “taxes on domestic asset and foreign exchange transactions – so-called Keynes and Tobin taxes – reserve requirements on capital inflows (so-called Chilean regulations), foreign exchange restrictions, and so-called trip-wires and speed bumps, which are early warning systems combined with temporary policies to slow down the excessive inflows and/or outflows of capital.” Pollin reckons that by “taxing the excesses of financialization and channeling the revenue appropriately, governments can help to restore public services and investments which, otherwise, are among financialization’s first and most severe casualties.” This is no more radical than the policy prescriptions of Joseph Stiglitz, the ‘progressive’ Nobel prize winning economist who said, “I am no left-winger, I’m a middle of the road economist”.

Most important, if ‘financialisation is not the cause, such reforms of finance won’t work in ending rising inequality or regular and recurring slumps in economies. The financialisation school needs to remember what one of its icons, Joan Robinson once said: “Any government which had both the power and will to remedy the major defects of the capitalist system would have the will and power to abolish it altogether”.

No comments:

Post a Comment