This year’s conference of the International Initiative for the Promotion of Political Economy (IIPPE) in Pula, Croatia had the theme of The State of Capitalism and the State of Political Economy. Most submissions concentrated on the first theme although the plenary presentations aimed at both.

I was struck by the number of papers (IIPPE 2018 – Abstracts) on the situation in Brazil, China and Turkey – a sign of the times – but also by the relative youth of the attendees, particularly from Asia and the ‘global south’. The familiar faces of the ‘baby boomer’ generation of Marxist and heterodox economists (my own demographic) were less in evidence.

Obviously I could not attend all simultaneous sessions so I concentrated on the macroeconomics of advanced capitalist economies. Actually my own session was among the first of the conference.

Under the title of The limits to economic policy management in the era of financialisation, I presented a paper on The limits of fiscal policy (my PP presentation is here (The limits to fiscal policy).

I argued that, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, Keynes had recognised that monetary policy would not work in getting depressed economies out of a slump, whether monetary policy was ‘conventional’ (changing the interest rate for borrowing) or ‘unconventional’ (central banks buying financial assets by ‘printing’ money). In the end, Keynes opted for fiscal stimulus as the only way for governments to get the capitalist economy going.

In the current Long Depression, now ten years old, both conventional (zero interest rates)and unconventional (quantitative easing) monetary policy has again proved to be ineffective. Monetary easing had instead only restored bank liquidity (saved the banks) and fuelled a stock and bond market bonanza. The ‘real’ or productive economy had languished with low real GDP growth, investment and wage incomes.

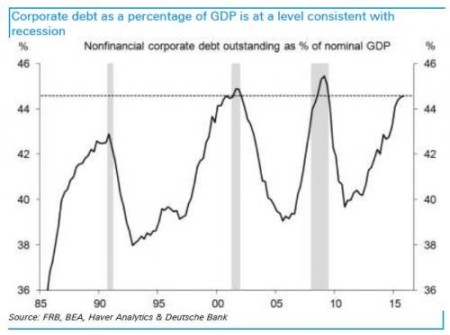

Maria Ivanova of Goldsmiths University of London also presented in my session (Ivanova_Quantitative Easing_IJPE_forthcoming) and she showed clearly that both conventional and unconventional monetary policies adopted by the US Fed had done little to help growth or investment and had only led to a new boom in financial assets and a sharp rise in corporate debt, now likely to be the weak link in the circulation of capital in the next slump.

Keynesian-style fiscal stimulus was hardly tried in the last ten years (instead ‘austerity’ in government spending and budgets was generally the order of the day). Keynesians thus continue to claim that fiscal spending could have turned things around. Indeed, Paul Krugman argued just that in the New York Times as the IIPPE conference took place.

But in my paper, I refer to Krugman’s evidence for this and show that in the past government spending and/or running budget deficits have had little effect in boosting growth or investment. That’s because, under a capitalist economy, where 80-90% of all productive investment is by private corporations producing for profit, it is the level of profitability of capital that is the decisive factor for growth, not government spending boosting ‘aggregate demand’. In the last ten years since the Great Recession, while profits have risen for some large corporations, average profitability on capital employed has remained low and below pre-crash levels (see profitability table below based on AMECO data). At the same time, corporate debt has jumped up as large corporations borrow at near zero rates to buy their own share (to boost prices) and/or increased payouts to shareholders.

Government spending on welfare benefits and public services along with tax cuts to boost ‘consumer demand’ is what most modern Keynesians assume is the right policy. But it would not solve the problem (and Keynes thought so too in the 1940s). Indeed, what is required is a massive shift to the ‘socialisation of investment’, to use Keynes’ term, i.e. the government should resume responsibility for the bulk of investment and its direction. During the 1940s, Keynes actually advocated that up to 75% of all investment in an economy should be state investment, reducing the role of the capitalist sector to the minimum (see Kregel, J. A. (1985), “Budget Deficits, Stabilization Policy and Liquidity Preference: Keynes’s Post-War Policy Proposals”, in F. Vicarelli (ed.), Keynes’s Relevance Today, London, Macmillan, pp. 28-50).

Of course, such a policy has only happened in a war economy. It would be quickly opposed and was dropped in ‘peace time’. That’s because it would threaten the very existence of capitalist accumulation, as Michal Kalecki pointed out in his 1943 paper.

Now in 2018, the UK Labour Party wants to set up a ‘Keynesian-style’ National Investment Bank which would invest in infrastructure etc, alongside the big five UK banks which will continue to conduct ‘business as usual ‘ i.e. mortgages and financial speculation. Under these Labour proposals, government investment (even if implemented in full) would rise to only 3.5% of GDP, less than 20% of total investment in the economy – hardly ‘socialisation’ a la Keynes at his most radical.

But perhaps President Trump’s version of Keynesian fiscal stimulus (huge tax cuts for the rich and corporations , driving up the budget deficit) will do the trick. It is an irony that it is Trump that has adopted Keynesian policy. He certainly thinks it is working – with the US economy growing at a 4% annual rate right now and official unemployment rates at near record lows. But an excellent presentation by Trevor Evans of the Berlin School of Economics poured cold water on that optimism. With a barrage of data, he showed that corporate profits are actually stagnating, corporate debt is rising and wage incomes are flat, all alongside highly inflated stock and bond markets. The Trump boom is likely to fizzle out and turn into its opposite.

Also, Arturo Guillen of the Metropolitan University of Mexico City,( IIPPE 2018 inglés) reminded us that the medium term trajectory of US economic growth was very weak with productivity growth very low and productive investment crawling. In that sense, the US was suffering from ‘secular stagnation’, but not for the reasons cited by Keynesians like Larry Summers (lack of demand) or by neoclassical critiques like Robert Gordon (ineffective innovation) but because of the low profitability for capital.

In another session, Joseph Choonara, took this further. Choonara saw the current crisis rooted in a long decline in profitability in the period from the late 1940s to the early 1980s. The subsequent neoliberal period developed new mechanisms to defer crises, notably financialisation and credit expansion. In the Long Depression since 2009, driven largely by the central bank response, debt continues to mount. The result is a financially fragile and uncertain recovery, which is creating the conditions for a new crisis

There were also some sessions on Marxist economic theory at IIPPE, including a view on why Marx sent so much time on learning differential calculus (Andrea Ricci) and on why Marx’s transformation of value into prices of production is dialectical in its solution (Cecilia Escobar). Also Paul Zarembka from the University of Buffalo, US presented a paper arguing that the organic composition of capital in the US did not rise in the post-war period and so cannot be the cause of any fall in the rate of profit.

His concepts and evidence do not hold water in my view. Zarembka argues that there is a major problem concerns using variable capital v in the denominator in the commonly-expressed organic composition of capital, C/v. That is because v can change without any change in the technical composition. Using, instead, what he calls the ‘materialized composition of capital’, C/(v+s), movement in C/v can be separated between the technical factor and the distributional factor since C/v = (1 + s/v). With this approach, Zarembka reckons, using US data, he can show no rise in the organic composition of capital in the US and no connection between Marx’s basic category for laws of motion under capitalism and the rate of profitability.

But I think his category C/(v+s) conflates the Marx’s view of the basic ‘tendency’ (c/v) in capital accumulation with the lesser ‘counter-tendency’ (s/v) and thus confuses the causal process. This makes Marx’s law of profitability ‘indeterminate’ in the same way that Sweezy and Heinrich etc claim. As for the empirical consequences of rejecting Zarembka’s argument, I refer you to an excellent paper by Lefteris Tsoulfidis.

As I said previously, there were a host of sessions on Brazil, Southern Africa and China, most of which I was unable to attend. On China, what I did seem to notice was that nearly all presenters accepted that China was ‘capitalist’ in just the same way as the US or at least as Japan or Korea, if less advanced. And yet they all recognised that the state played a massive role in the economy compared to others – so is there a difference between state capitalism and capitalism? I cannot say anything about the papers on Brazil except for you to look at IIPPE 2018 – Abstracts. Brazil has an election within a month and I shall cover that then – and these are my past posts on Brazil.

There were other interesting papers on automation and AI (Martin Upchurch) and on bitcoin and a cashless economy (Philip Mader), as well as on the big issue of imperialism and dependency theory (which is back in mode).

The main plenary on the state of capitalism was addressed by Fiona Tregena from the University of Johannesburg. Her primary area of research is on structural change, with a particular focus on deindustrialisation. Prof Tregena has promoted the concept of premature deindustrialisation.

Premature deindustrialisation can be defined as deindustrialisation that begins at a lower level of GDP per capita and/or at a lower level of manufacturing as a share of total employment and GDP, than is typically the case internationally. Many of the cases of premature deindustrialisation are in sub‐Saharan Africa, in some instances taking the form of ‘pre‐industrialisation deindustrialisation’. She has argued that premature deindustrialisation is likely to have especially negative effects on growth.

As for the state of political economy, Andrew Brown of Leeds University has explained some of the failures of mainstream economics, particularly marginal utility theory. Marginal utility theory has not to this day been developed in a concrete and realistic direction not because it is just vulgar apologetics for capitalism, but because it is theoretically nonsense. Marginal utility theory can provide no comprehension of the macroeconomic aggregates that drive the reproduction and development of the economic system.

‘Financialisation’ is the word/concept that dominates IIPPE conferences. It is a concept that has some value when it describes the change in the structure of the financial sector from pure banks to a range of non-deposit financial institutions and the financial activities of non-financial corporations in the last 40 years.

But I am not happy with the concept when it used to suggest that the financial crash and the Great Recession were the result of some new ‘stage’ in capitalism. From this, it is argued that crises now occur not because of the fall in productive sectors but because of the speculative role of ‘’financialisation.’ Such an approach , in my view, is not only wrong theoretically but does not fit the facts as well as Marx’s laws of motion: the law of value, the law of accumulation and the law of profitability.

For me, financialisation is not a new stage in capitalism that forces us to reject Marx’s laws of motion in Capital and neoliberal economics is not in some way the new economics of financialisation and a different theory of crises from Marx’s. Finance does not drive capitalism, profit does. Finance does not create new value or surplus value but instead finds new ways to circulate and distribute it. The kernel of crises thus remains with the production of value. Neoliberalism is merely a word invented to describe the last 40 years or so of policies designed to restore the profitability of capital that fell to new lows in the 1970s. It is not the economics of a new stage in capitalism.

Sure, each crisis has its own particular features and the Great Recession had that with its ‘shadow banking’, special investment vehicles, credit derivatives and the rest. But the underlying cause remained the profit nature of the production system. If financialisation means the finance sector has divorced itself from the wider capitalist system, in my view, that is clearly wrong.

No comments:

Post a Comment