There is a new dataset on world trade that looks at changes in exports and imports globally going back to 1800 and the beginnings of modern industrial capitalism. Two authors, Giovanni Federico, Antonio Tena-Junguito have presented a number of papers on the trends found in the data.

Their main conclusions are that trade grew very fast in the ‘long 19th century’ from Waterloo to WWI, recovered from the wartime shock in the 1920s, and collapsed by about a third during the Great Depression. It grew at breakneck speed in the Golden Age of the 1950s and 1960s and again, after a slowdown because of the oil crisis, from the 1970s to the outbreak of the Great Recession in 2007. The effect of the latter on trade growth is sizeable but almost negligible if compared with the joint effect of the two world wars and the Great Depression. “However, the effects might become more and more comparable if the current trade stagnation continues”.

The data show that there were two major periods of ‘globalisation’, if you like. The first was from 1830-70 when the export to GDP ratio, a measure of openness in trade, rose. The second was from the mid-1970s to 2007 – the great globalisation period of the 20th century. According to the data, the current level of openness to trade is unprecedented in history. The export/GDP ratio at its 2007 peak was substantially higher than in 1913.

There were two periods of stagnation or decline in global trade expansion: during the depression of the late 19th century up to the start of WW1 and then in the 1930s Great Depression. Indeed, “openness collapsed during the Great Depression, back to the mid-19th century level.”

Now we appear to be in another downturn in globalisation and trade. “Since 2007, the apparently unstoppable growth of world trade has come to a halt, and the openness of the world economy has been stagnating, or even declining. The recent prospect of a trade war is fostering pessimism for the future. Some people are hinting at a repetition of the Great Depression”, conclude the authors.

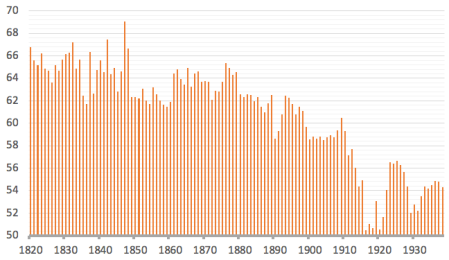

As you would have expected, the rise of industrial capitalism globally meant that the share of agricultural and mineral products in total exports declined for both advanced capitalist (imperialist) countries and (interestingly) for the peripheral (colonial) economies. The share of primary products fell from about 65% in the 1820s to slightly above 55% on the eve of WWI, with an acceleration of the trend around 1860 (as industrialisation spread).

The big change was the move of America from an agriculture exporter to industrial giant in the 20th century. The continued rise in industrial and services trade in the late 20th century globalisation has been in turn been led by China’s transformation from a poor agricultural peasant economy into the manufacturing (and increasingly hi-tech) workshop of the world.

Share of primary products on exports, baseline series, 1820–1938

The data in general confirm that my own study of globalisation and imperialism that I recently presented.

In my thesis, I argue that globalisation and increased trade are responses by capitalism to falling profitability and then depression in a previous period. Globalisation of trade and capital took off whenever profitability of capital fell in the imperialist centres.

Between 1832-48, profitability of capital in the major economies fell; after which there was an expansion of globalization to drive up profitability (1850-70). However, a new fall in profitability led to the first depression of the late 19th century (1870-90), during which protectionism rose and capital flows shrunk. With economic recovery after 1890, imperialist rivalry intensified, leading up to the Great War of 1914-18.

Again after the defeats of various labour struggles post 1945 in Europe, Japan and in the colonial territories, capitalism entered a new ‘golden age’ of relatively fast growth and rising profitability. Globalisation of trade (reduction in tariffs and protectionism) and capital (dollar-led economies and international institutions) revived, until profitability again began to fall in the 1970s. The 1970s saw a weakening of trade liberalization and capital flows. From the 1980s however, capitalism saw a new expansion of globalization in trade and capital to restore profitability.

The beginning of the 21st century brought to an end this wave of globalisation. Profitability in the major imperialist economies peaked by the early 2000s and after the short credit-fuelled burst of up to 2007, they entered the Great Recession, which was followed by a new long depression. Like that of the late 19th century, this brought to an end globalisation. World trade growth is now no faster than world output growth, or even slower.

So the counteracting factor to low profitability offered by exports, trade and credit has died away. This threatens the hegemony of US imperialism, already in relative decline to new ambitious powers like China, India and Russia. With US President Trump now launching his attempt to put the US back in the driving seat for international trade, renewed rivalry threatens to unleash major conflicts in the next decade or so.

No comments:

Post a Comment