Last week, to commemorate 170 years since Marx and Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto, the editors of the UK’s Financial Times commissioned two executives of a ‘corporate advisory’ firm to consider what was right and wrong in that seminal work about capitalism and communism. The two FT writers started by declaring that “as a partner in a corporate advisory firm and a professor of law and finance, we are true believers in free-market capitalism”, but nevertheless, the 1848 manifesto still had some value, especially “in the wake of a calamitous financial crisis and in the midst of whirlwind social change, a popular distaste of financial capitalists, and widespread revolutionary activity”.

But the FT authors wanted to convert the Communist Manifesto into what they call a “Activist Manifesto”. They threw out the outdated concepts of two classes: capitalists and workers; and replaced them with the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’. You see, classes and crises are out of date as the main critique of capitalism now is rising inequality, which the FT authors claim the Communist Manifesto was really about. “As in Marx’s and Engels’ time, economic inequality is rising, wages are stagnating, and the owners of productive capital are reaping the benefits of technological advances”.

But the solution to this, the FT authors are at pains to say, is not the confiscation of private property or communism – this only breeds “murderous tyrannies”. And “we also think Marx and Engels would update their views about private property. While the abolition of private property was their first and most prominent demand, we think they would recognise that Have-Nots have benefited from property rights. Moreover, we argue that state-held property is problematic, leading to waste, inefficiency and the likelihood of being co-opted by the Haves in our societies today. As the role of the state has grown, inequality has also grown. And the Have-Nots have been the ones who have paid for it.”

Instead what we need is ‘shareholder activism’ in companies “shaking up complacent boards and advocating for changes in corporate strategy and capital structure.” This is the way forward, according to our FT authors 170 years after Marx and Engels’ manifesto. And even the global elite recognise it: “many Haves too are activists already today… Think of the billionaires such as Bill Gates, Warren Buffett and Mark Zuckerberg, who already support philanthropic efforts to alleviate inequality”. So that’s all right then.

Should the Communist Manifesto be rewritten as a plea for ‘activism’ led by billionaires to reduce inequalities, rather than the abolition of private property in the means of production and the replacement of capitalism with communism? While the FT was publishing its view on the Communist Manifesto today, I was delivering a talk on social classes today at the Metropolitan University of Mexico in Mexico City (Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana – UAM) as part of my recent visit there. I too started off with a reminder that it was 170 years since the Communist Manifesto was published. But I emphasised that the basic division of capitalism between two classes: the owners of the means of production (corporations globally) and those who own nothing and only have their labour power to sell; remains pretty much unchanged from how it was in 1848.

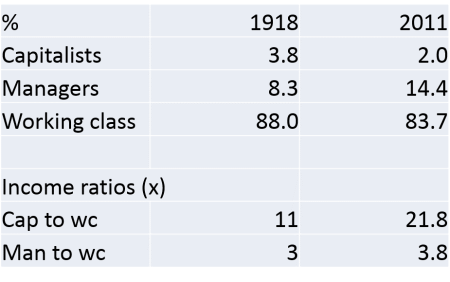

Recent empirical work on the US class division of incomes has been done by Professor Simon Mohun. Mohun analysed US income tax returns and divided taxpayers into those who could live totally off income from capital (rent, interest and dividends) – the true capitalists, and those who had to work to make a living (wages). He compared the picture in 1918 with now and found that only 3.8% of taxpayers could be considered capitalists, while 88% were workers in the Marxist definition. In 2011, only 2% were capitalists and near 84% were workers. The ‘managerial’ class, ie workers who also had some income from capital (a middle class ?) had grown a little from 8% to 14%, but still not decisive. Capitalist incomes were 11 times higher on average than workers in 1918, but now they were 22 times larger. The old slogan of the 1% and the 99% is almost accurate.

The class divide described in the Communist Manifesto is that between those who own and those who do not and Mohun’s ‘class’ stats confirm that. For Marx and Engels, all previous history has been one of class struggle over the surplus created by labour. In slave economies, the owners of capital literally owned humans as source of their surplus; in feudal society, they controlled the days of work and obligations of the serfs.

Under capitalism, the surplus was usurped in a hidden ‘invisible’ way. Workers were paid a wage – a fair wage – but they produced more value in the commodities they made for sale and it was this surplus value realised in the sale of commodities (goods and services) that capitalists accumulated.

The class struggle under capitalism thus took the form of a struggle between the share of value going to wages or profits. As Marx put it in Capital: “In the class struggle as a finale in which is found the solution of the whole smear! From a struggle over wages, hours and working conditions or relief, it becomes, even as it fights for those things, a struggle for the overthrow of the capitalist system of production – a struggle for proletarian revolution.”

In my presentation to UAM in Mexico, I ambitiously argued that we can gauge the intensity of the class struggle from the balance of forces in the wage-profit battle. I used statistics of strikes in the UK since 1890 against the profitability of UK capital (for more on this, see my paper, Mapping out the class struggle). The first long depression of capitalism was at its deepest just as Marx died in 1883. It came to an end in the UK in the early 1890s: profitability recovered and the labour movement strengthened with the advent of new mass unions. Labour disputes erupted for a while. The fall back in profitability from 1907 then sparked a new battle over the surplus leading to intense levels of strikes just before the WWI broke out.

After the war, the class struggle resumed with some intensity, but in the UK that ended with the defeat of the general strike in 1926. On the back of that defeat, UK capital recovered some profitability while the unions were weakened. Strikes and class struggle were depressed by the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The second world war drove up profitability and the labour movement also made a recovery. It was the golden age of growth, investment, employment and the ‘welfare state’. So when the profitability crisis of the late 1960s and 1970s commenced, British workers fought hard to maintain their gains. Strikes were at a high level and there was talk of revolution. That struggle came to an end with the defeat of the miners in 1985. What followed was rising profitability in the neo-liberal period, along with weakened trade unions. This was a recipe for low levels of class struggle. With the Great Recession and the subsequent Long Depression, that low intensity continued.

I concluded from this short analysis that the class struggle as described in the Communist Manifesto has not disappeared and neither have the two basic classes, contrary to the amendments advocated in the ‘Activist Manifesto’ of the FT authors. But the intensity of that struggle depends on the objective conditions of the profitability of capital and the strength of labour. Class struggle is not always at fever pitch, revolutionary moments are rare.

The most intense periods of struggle appear to be when the labour movement is reasonably strong in incomes and organisation but when the profitability of capital has started to fall, according to Marx’s law of profitability. Then the battle over the share of the surplus and wages rises. Historically, in the UK that was from 1910 just before and just after WW1; and in the 1970s. Such objective conditions have so far not arisen again. So the spectre of Communism haunting Europe – the phrase that Marx and Engels started with their manifesto in 1848 (in a similar intense period as those above) – is not yet with us again.

No comments:

Post a Comment