The latest economic data are showing that economic growth in the major capitalist countries has been picking up in the first half of 2017.

Japan’s economy expanded at the fastest pace for more than two years in the three months to June, with domestic spending accelerating as the country prepares for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

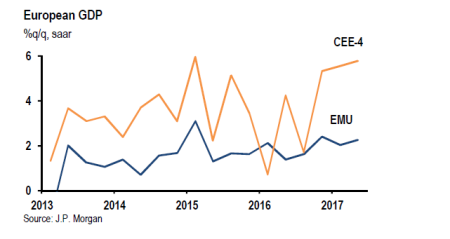

In the Eurozone, real GDP growth rose at annualised rate of 2.5%, with the Visegrad countries of Czech, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia rising at 5.8% in the second quarter of this year.

With the US economy continuing to trundle along at just over a 2% a year growth, the major economies are looking a little brighter in growth terms, it seems – at least compared to the falling growth rates of 2015-6.

What has been the key reason for this slight improvement? In my view, it is the relative recovery in the Chinese economy, considered by most observers and the evidence as the driver of world economic growth (at the margin) since 2007. As the IMF put it in its latest survey of the Chinese economy, “With many of the advanced economies of the west struggling in the years since the financial crisis of 2007-09, China has acted as the growth engine of the global economy, accounting for more than half the increase in world GDP in recent years.”

Manufacturing output in China increased 6.7% yoy in July, continuing a slight recovery in 2017 after reaching a low in 2016 from a peak of over 11% a year in 2013. As a result, Eurozone manufacturing output has picked up, particularly in Germany, the Netherlands and Italy as they export more to China. The US manufacturing sector has also reversed its actual decline in 2016. Japan’s manufacturing sector leaped up 6.7% compared to 2016, led by construction demand for the Olympics.

This all looks much better. But remember most of these major economies are still growing at only around 2% a year, still well below pre-2007 rates or even the average in the post-1945 period. The ‘developed’ capitalist economies are growing at their slowest rate in decades. Ruchir Sharma, chief global strategist and head of emerging markets at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, noted in a recent essay in the magazine Foreign Affairs that “no region of the world is currently growing as fast as it was before 2008, and none should expect to. In 2007, at the peak of the pre-crisis boom, the economies of 65 countries – including a number of large ones, such as Argentina, China, India, Nigeria, Russia and Vietnam – grew at annual rates of 7% or more. Today, just six economies are growing at that rate, and most of those are in small countries such as Côte d’Ivoire and Laos.”

Nevertheless, all the purchasing managers indexes (PMIs) that provide the best ‘high frequency’ guide to the attitude and confidence of the capitalist sector in each country all show expansion is still taking place – if not at the pace of 2013-14. Again the key seems to be a recovery in China’s PMI.

What does all this tell us about the likelihood of a new global economic recession in the next year or two? That is something that I have been forecasting or expecting. The latest data would seem to point away from that.

The mainstream forecasters remain optimistic about growth with the only proviso being that it is China that might collapse. The IMF survey makes the familiar argument of the mainstream that overall debt is so high that it will eventualy collapse in bankruptcies and defaults, causing a slump and weakening the world economy. Total debt has quadrupled since the financial crisis to stand at $28tn (£22tn) at the end of last year.

I disagree: for two reasons. First, when China’s growth slowed sharply at the beginning of 2016, the mainstream observers argued that China could bring the world economy down. My view was that, important as the Chinese economy was, it was not large enough to take the US and Europe down. Those advanced economies remained the key to whether there would be a world slump. And so it has proved.

Second, the size of China’s debt is large but the Chinese economy is different from the advanced capitalist economies. Most of that debt is owed by the Chinese state banks and state enterprises. The Chinese government can bail these entities out using its reserves and forced savings of Chinese households. The state has the economic power to ensure that, unlike governments in the US and Europe during the credit crunch of 2007. Governments then were beholden to the capitalist banks and companies, not vice versa. So any credit crisis in China will be dealt with without producing a major collapse in the economy, in my view.

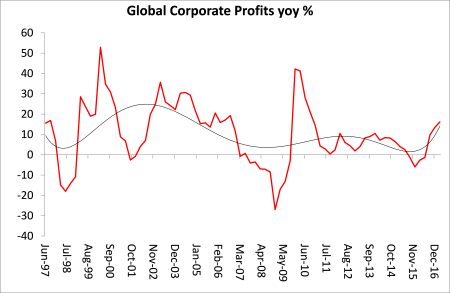

So does this mean that a new world slump is off the agenda? No, in short. One of my key indicators of the health of capitalist economies, as the readers of this blog well know, is the movement of profits in the capitalist sector. Global corporate profits (a weighted average of the major economies) have also made a significant recovery from their collapse at the end of 2015. Indeed corporate profits overall seem to rising at the fastest rate since the immediate bounce-back after the end of the Great Recession.

But this overall figure is driven by the Chinese recovery and the pickup in Japan (due to the Olympics construction?). Corporate profit growth in the US, Germany and the UK is slowing again after a brief pick-up in late 2016.

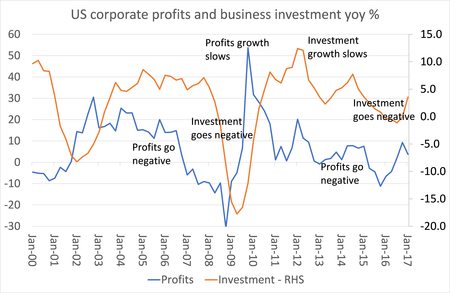

For me, the key remains the state of US economy and in particular, profits and investment levels there. The booming US stock market is now way out of line with corporate earnings levels. The S&P 500 cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) valuation has only been higher on one occasion, in the late 1990s. It is currently on par with levels preceding the Great Depression.

US corporate profits have recovered in the last few quarters after declining (although now slowing again) and, along with that, business investment has picked up. Watch this space over the rest of 2017 to see if this is sustained.

Total domestic corporate profits have grown at an annualized rate of just 0.97% over the last five years. Prior to this period five-year annualized profit growth was 7.95%. At $8.6 trillion, corporate debt levels are 30% higher today than at their prior peak in September 2008. At 45.3%, the ratio of corporate debt to GDP is at historic highs, having recently surpassed levels preceding the last two recessions. If there is an issue with the level of debt, it is in the US, not in China.

No comments:

Post a Comment