A number of readers of this blog have remarked or asked me to comment on a recent article in the Economist magazine that asserted that both profits and even the return on capital or profitability in the US are at “near-record highs”. As quoted, “The past two decades have seen most firms make more money than they used to. And more firms have become very profitable”.

This would seem to be in contradiction to the assertions and evidence continually made by me in this blog and elsewhere that US profitability has been in secular decline since 1945 and is near post-war lows not highs.

This contradiction can be resolved in several ways. The first is what one blog reader pointed out: we are comparing apples with pears; the second is that we are comparing harvests of apples and pears at different times; and third, we are looking at the best apples, and not the bulk of the rotten ones.

On apples and pears: it is obviously true that US corporate profits are higher in absolute terms than they were 30 years ago. US national output is higher, the population is higher, employment of labour is higher, investment is higher.

Of course, the Economist is not so crude as to measure the health of the US economy in absolute profits. This is what it said: “The last year has seen a slight dip in aggregate profits because of the high dollar and the effect of the oil price on energy firms. But profits are at near-record highs relative to GDP and free cash flow—the money firms generate after capital investment has been subtracted—has grown yet more strikingly. Return on capital is at near-record levels, too (adjusted for goodwill). The past two decades have seen most firms make more money than they used to. And more firms have become very profitable.”

Now some of this is true. Corporate profits to GDP are still near post-war highs. But this measure is not a measure of profitability against capital. Profitability of capital invested is measured as profits divided by the value of stock of the means of production owned and used by corporations and the cost of employing the labour force to use them. In Marx’s formula, this is s/c+v. Profits to GDP is really the share of value created going to capital and is much closer to the Marxist rate of surplus value, s/v. That’s why it is possible to have high corporate profits to GDP and low profitability of capital. Which is more relevant to how well US capitalism will do is open to discussion: is it the apples of profit share or the pears of profitability?

The Economist purports to measure the profitability of capital too with its ‘global return on capital’. However, this is a measure not of the profitability of the stock of capital in US corporations but the annual rate of return on invested capital (including financial assets) domestically and globally by US corporations, as compiled by the McKinsey Institute. That annual return, according to the graph, was actually flat until 2002 and then rocketed. That reflects US corporations’ investment returns from buying its own shares and investing in foreign assets in the period since 2002, not the overall profitability of US capital stock in productive assets. Again, it is a matter of debate whether the Marxist measure of profitability is more relevant than the rate of return on American capital as defined by McKinsey.

Moreover, the McKinsey measure reflects the profitability of the largest and most profitable US corporations. As the Economist piece explains, taking its data from the McKinsey Institute annual corporate valuation report, there is a huge variance in profitability among US companies, with the lion’s share going to the top four firms in each sector of US industry and services. As the Economist says, profitability is highest and has risen most in the more oligopolistic sectors. “Revenues in fragmented industries—those in which the biggest four firms together control less than a third of the market—dropped from 72% of the total in 1997 to 58% in 2012. Concentrated industries, in which the top four firms control between a third and two-thirds of the market, have seen their share of revenues rise from 24% to 33%.” So some apples are doing very well, but many apples are in a sorry state.

Actually, the Economist does not like this monopolistic development in the US corporate sector: it wants ‘more competition’. More competition would mean lower profitability but would also drive corporations to be more efficient. “High profits across a whole economy can be a sign of sickness. They can signal the existence of firms more adept at siphoning wealth off than creating it afresh, such as those that exploit monopolies. If companies capture more profits than they can spend, it can lead to a shortfall of demand. This has been a pressing problem in America. It is not that firms are underinvesting by historical standards. Relative to assets, sales and GDP, the level of investment is pretty normal. But domestic cash flows are so high that they still have pots of cash left over after investment: about $800 billion a year.”

Much of this argument is nonsense. As I have explained in a recent article in the Jacobin magazine that took up similar arguments by Goldman Sachs: “Goldman Sachs’s declaration that falling profit margins are a measure of the “efficacy” of capitalism and a return to “normal” sounds pretty hollow. It disguises the real issue. High profit margins are masking a broader decline in corporate profitability and the depressing likelihood that an economic recession — and its inevitable negative impact on working people in lost jobs, incomes and homes— is once again on the horizon, only eight years after the end of biggest slump in the American economy since the 1930s..This is the real measure of capitalism’s efficiency for the 99%.”

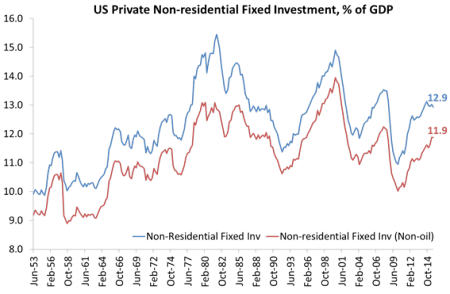

It’s not that profits are so high that they cannot be spent; it’s that corporations don’t want to invest because profitability is too low and debt is too high. It’s not true that the level of US business investment is “pretty normal”. As a share of GDP, since the 1980s, it has been steadily falling and its growth is now slowing.

Moreover, corporate profits in the US are now falling and if this continues, business investment will drop, not rise as the Economist thinks. I have shown before how the correlation and causal connection flows from profits to investment. This something that even mainstream investment pundits like Albert Edwards have noticed recently (see Edwards’ graph below).

As for cash piles, I have discussed the nature of these cash reserves in posts before: they are concentrated in the very large US multi-national and relative to overall financial assets and rising debt, these cash reserves are not particularly large.

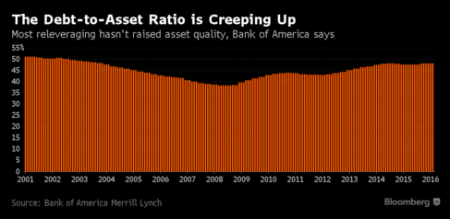

Corporate cash piles among the largest US multi-nationals go alongside rising corporate debt for the majority.

US non-financial corporate debt to GDP (%)

I have shown this in several posts and the risk of corporate debt defaults will rise as profits and profitability falls. Losses on bonds from defaulted companies are likely to be higher than in previous cycles, because U.S. issuers have more debt relative to their assets, according to Bank of America Corp. strategists. Those high levels of borrowings mean that if a company liquidates, the proceeds have to cover more liabilities.

Leverage levels have been rising as more US companies use borrowings to refinance existing liabilities, buy back shares and take other steps that do not increase asset values.

And global corporate debt is rising too. According to McKinsey, at the end of 2007 the global stock of outstanding debt stood at $142 trillion. Then in 2008 the financial world fell apart. Less than seven years later, in mid-2014, there is an additional $57 trillion in global debt, and the data this year is going to show that we’ve hit another record high. Debt as a percentage of GDP is even higher now than it was in 2007: 286% vs. 269%. Total debt grew at a 5.3% annual rate from 2007–14. But corporate debt grew even faster at 5.9% annually.

The global corporate default ratio has climbed to its highest level in seven years, led by oil and gas companies. This month saw four new major corporate defaults, which took the overall tally to 40 for 2016, ratings agency Standard & Poor’s said. That’s the highest year-to-date default tally since 2009. Of those, 14 defaults came from the oil and gas sector and a further eight from the metals, mining, and steel sector. The overall default tally for the same time last year was 29. Companies in the US saw the biggest default rate with 34, with five in the emerging markets.

I referred to the McKinsey study in a previous post. What McKinsey (MGI Global Competition_Executive Summary_Sep 2015) found was that “the world’s biggest corporations have been riding a three-decade wave of profit growth, market expansion, and declining costs. Yet this unprecedented run may be coming to an end”. According to McKinsey, the global corporate-profit pool, which currently stands at almost 10% of world GDP, could shrink to less than 8% by 2025—undoing in a single decade nearly all of the corporate gains achieved relative to the world economy during the past 30 years!

From 1980 to 2013, vast markets opened around the world while corporate-tax rates, borrowing costs, and the price of labour, equipment, and technology all fell. The net profits posted by the world’s largest companies more than tripled in real terms from $2 trillion in 1980 to $7.2 trillion by 2013, pushing corporate profits as a share of global GDP from 7.6% to almost 10%.

But McKinsey reckons that profit growth is coming under pressure. This could cause the real-growth rate for the corporate-profit pool to fall from around 5% to 1%, to practically the same share as in 1980, before the boom began. According to McKinsey, margins are being squeezed in capital-intensive industries, where operational efficiency has become critical. Meanwhile, some of the external factors that helped to drive profit growth in the past three decades, such as global labour arbitrage (globalisation) and falling interest rates, are reaching their limits.

So, in a way, the Economist is out of date. Corporate profits as a share of GDP are falling and are set to fall further over the next decade. The apple harvest will be less each year. The boom days of the ‘neoliberal’ period of 1980 to 2007 are over. As I have shown in previous posts, global corporate profit growth has ground to a halt and in the US corporate profits are not only falling as a share of GDP, but also in absolute terms.

Far from a reduction of ‘too high profits’ being a good thing in boosting ‘competition and efficiency’ as the Economist claims, falling US corporate profits and profitability will herald a drop in investment and increase of corporate debt defaults and so lay the foundations for a new economic slump.

No comments:

Post a Comment