The debate within mainstream economists and between those economists working for financial institutions continues. The stock and bond markets appear to be pricing in the real possibility of the US economy dropping into recession (as defined by two consecutive quarters of contraction in real GDP) in 2016.

However, the majority view of mainstream economics is that a US recession is unlikely and that the US economy will pick up again during this year. That’s certainly the position of the US Federal Reserve under Janet Yellen, who presented that argument in her testimony to the US Congress last week. “Financial conditions in the United States have recently become less supportive of growth, with declines in broad measures of equity prices, higher borrowing rates for riskier borrowers, and a further appreciation of the dollar. These developments, if they prove persistent, could weigh on the outlook for economic activity and the labor market, although declines in longer-term interest rates and oil prices provide some offset. Still, ongoing employment gains and faster wage growth should support the growth of real incomes and therefore consumer spending, and global economic growth should pick up over time, supported by highly accommodative monetary policies abroad. Against this backdrop, the Committee expects that with gradual adjustments in the stance of monetary policy, economic activity will expand at a moderate pace in coming years and that labor market indicators will continue to strengthen”.

And remember, when the US Fed hiked its policy interest rate for the first time in nearly ten years last December, Yellen commented that: that the US economy “is on a path of sustainable improvement.” and“we are confident in the US economy”, even if borrowing rates rise. The main arguments that the US economy is heading into recession this year are that the manufacturing and wider industrial sector is already slumping, not just in the US, but in all the major capitalist economies. And the collapse in oil prices has led to a huge drop in the profits and investment of the US energy sector, an important part of the economy. At the same time, the US dollar remains very strong compared to other trading currencies, so exports are doing badly and US external trade is now a drag on growth.

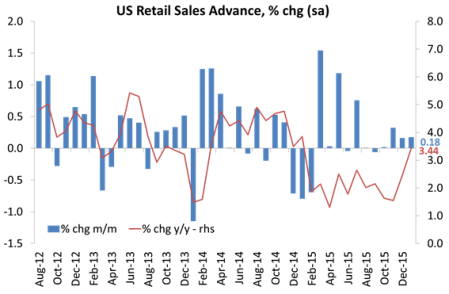

However, the counter-argument is that while industrial production may be falling, the American consumer is still spending robustly, the housing market is picking up and retail sales (whether through the shops, auto dealers or on the internet) are still motoring.

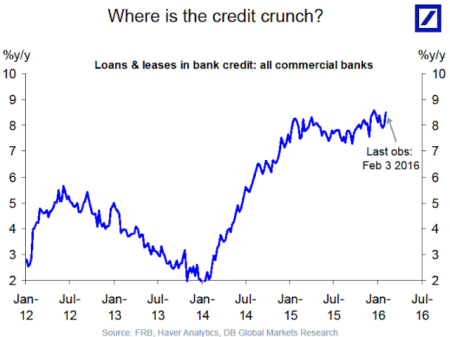

Deutsche Bank economist Torsten Sløk sums up this view: “The challenges in the energy sector are not spilling over to the broader economy and the macro data is not deteriorating … Despite the macro data doing well, pessimists often try to convince me that we are on the road to a full-blown credit crisis, which will push the economy into a recession, and we have been on this path since credit spreads started widening in July 2014. But if this is true, why did the data for January show an acceleration in consumer spending, a decline in the unemployment rate, an acceleration in wage inflation, and an increase in consumer confidence?” He added that “most importantly, if we for the past 18 months have been moving toward a credit crunch why is the weekly data for bank lending still showing no signs of a slowdown in bank lending?” Indeed, the latest release from the Federal Reserve showed that bank lending is right at its strongest levels since the financial crisis.

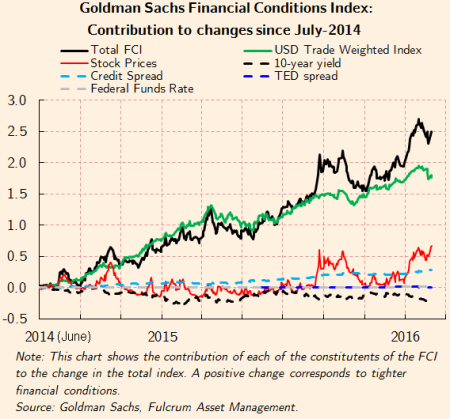

As for the last point on credit conditions, the view of Deutsche Bank’s Slok is open to question. Gavyn Davies in his FT blog points out that the strong dollar has tightened US financial conditions substantially. What that means is that exporters can’t sell and the cost of borrowing for companies has risen. He cites the Goldman Sachs Financial Conditions index.

The index suggests that there has been a tightening of about 250 basis points in the FCI since the dollar rise started in mid 2014. Jan Hatzius, now the Chief Economist at Goldman Sachs, calculates that this change in the GSFCI should already have reduced the annual GDP growth rate by around 1.0-1.5 per cent. He does not expect this impact to get worse during the rest of 2016, but his calculations are comfortably able to account for the slowdown in US growth to around 1.2 per cent since mid 2015, a growth rate that is well below trend.

In my blog, I have argued that what is important for the health of a modern capitalist economy is not the ease or cost of borrowing, as discussed by the mainstream economists above. It is the direction of average profitability of capital, total business profits and its impact on business investment. I have outlined a lot of data and arguments for these categories, showing that when profitability falls, eventually total corporate profits fall and then some time later, business investment will contract and when that happens, an economic recession soon follows.

This approach, Marxist in my opinion, is not usually supported (strangely) by most Marxist economists, let alone post-Keynesian or mainstream economics. However, recently some mainstream economists have paid the movement in profits a bit more attention. In my paper to the recent ASSA 2016 conference, I cited some recent studies by mainstream economists supporting the close causal connection between profits and business investment. And in the last month or so, the economists at the investment bank JP Morgan have started to use profits and profitability as a guide to the likelihood of an oncoming recession.

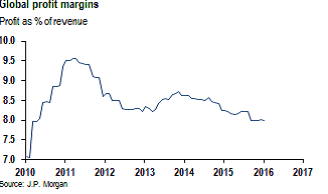

Now in their latest note, JP Morgan economists looked at US profit margins as a guide to a likely recession again (Daily Economic Brief, 11 February JPM and Global DataWatch, 13 February). JPM_Daily_Economic_Brief_2016-02-11_1942360

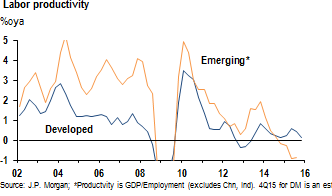

They first noted that global profit margins have been drifting lower for the past two years, mainly driven by a falling profitability in emerging capitalist economies as the great commodity price boom reversed and China’s economy slowed sharply.

Investment in plant, equipment ect had been inadequate in driving up the growth in the productivity of labour.

And now “DM (developed market) margins have begun to fall as US corporates come under pressure from the rising dollar and the concentrated hit to the energy sector.” JPM noted. In another note, JPM economists looked at overall US corporate profits and calculated that “corporate profits declined 30% saar in 4Q (-12%oya)…profits were likely down 11% annualized last quarter, and down 7% over year-ago levels.”

They then projected from regression models correlating profits with real GDP growth (something I also did in my ASSA paper) that “if taken literally, they now put the probability of a recession starting within three years at a startling 92%, and the probability within two years at 67%”.

However, they temper this result by pointing out that profit margins are still historically high so there is room for a fall without economic contraction and also the expectation that the US Fed will not continue with its rate hikes as quickly or as far as previously planned. On that basis, their forecast of a US recession is “beginning within three years at about 2/3 and within two years at close to 1/2″.

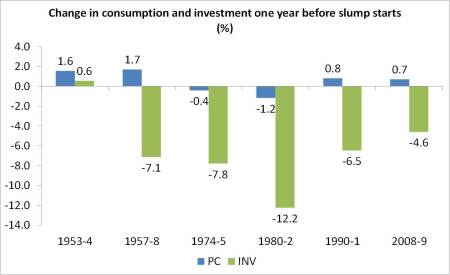

My own view has been expressed in previous posts: namely that a US and global recession will come within one to three years. The key deciders are two-fold: first the level of profits in the major economies must start falling and keep falling; and second, that this must lead to a sustained fall in business investment. It is the latter that causes slumps under capitalism because a fall in business investment means a loss of jobs and incomes for the workforce and that will multiply through to consumer spending (not vice versa as post-Keynesians claim). Those mainstream economists (including most Keynesians) who reckon that ‘the consumer’ can keep a capitalist economy going when business investment is collapsing are wrong. The evidence for the US is conclusive: in the post-war period US business investment has led the economy into slump while consumption stays more or less stable, the latter only falling once the slump is underway.

So far, US business investment has not started falling. In the last available figures for the end of 2015, it was rising at a 3% yoy pace, the slowest rate for two years. And the quarterly change in Q4 over Q3 was negative. But firm evidence that business investment is now consistently falling is not there yet.

No comments:

Post a Comment