This blog continually hammers home the view that it is investment not consumption that is the key to economic growth. Fluctuations in business investment in a predominantly business, profit-making economy decide, in the first analysis, whether output expands or contracts; whether there is a boom or slump. This view is contrary to that of Keynesian economics, which although it appears to recognise that investment plays an important role, sees investment and consumption spending (domestic demand) as driving employment, output and incomes and profit – in that order – not vice versa. And Keynesian economists often forget about the role of investment and talk as though all that matters is consumption spending.

This is also the view of neoclassical economics, when they consider the big macro questions of boom or slump (which they seldom do). The consumer is king (or queen) and, as it is the largest component of national output or expenditure, then it decides. However, being the largest component of national spending does not make consumption the ‘swing factor’ in growth. That is investment, particularly business investment.

This is something most socialist economists forget too, with the honourable exceptions of Michael Burke in the UK and John Ross based in China. See Michael Burke’s past posts and the latest post by John Ross, where he shows the powerful importance of capital investment (both in fixed and circulating constant capital) compared to ‘innovation, design and management’ as expressed in the nebulous concept of ‘total factor productivity’.

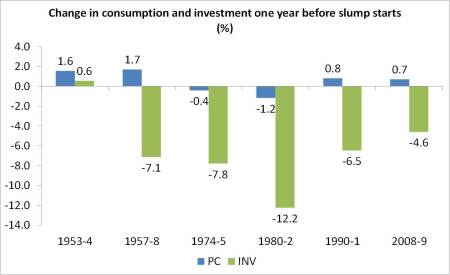

Also I have shown empirically that it is investment (particularly business investment) that is the swing factor. In all US economic recessions since 1945, it is investment that has fallen one year before the slump in GDP begins, while in nearly every recession, consumption spending continues (in the few exceptions where there was a fall in consumption prior to a recession, it was small).

In a recent article in Bloomberg, leading Keynesian blogger Noah Smith has suddenly noticed the role of investment. As he puts it: “The U.S. seems to be out of ideas for economic growth. The main argument appears to be over redistribution — tax rates, the size of the welfare state, free college. Protectionism is also making a comeback; Bernie Sanders would restrict trade and punish Wall Street, while Republican candidates would curb immigration. These are mostly debates about the size of the pie. But what about growing it?” Indeed, the concentration of economists of all hues, mainstream and heterodox has been on financialisation, inequalities of income and wealth and on ‘austerity’, not on the motors of economic growth.

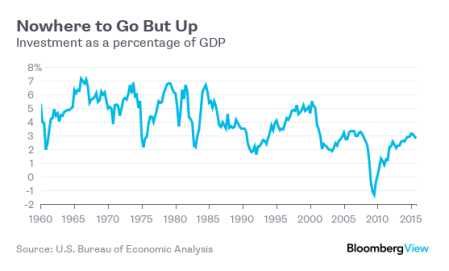

He goes on: “So what else is there? Looking around, I see the glimmer of a new idea forming. I’m tentatively calling it “New Industrialism.” Its sources are varied — they include liberal think tanks, Silicon Valley thought leaders and various economists. But the central idea is to reform the financial system and government policy to boost business investment.” He concludes that “Business investment — buying equipment, building buildings, training employees, doing research, etc. — is key to growth. It’s also the most volatile component of the economy, meaning that when investment booms, everything is good.” Exactly!

Smith then considers the issue of why “net U.S. business investment has been more or less in decline for decades”. Smith is not sure why. He poses a number of possible reasons: “This could be happening because investors don’t see much of a future for American businesses, and are thus choosing to get out while the getting is good. On the other hand, it could mean that investors are simply thinking in the short term and are more interested in quick cash grabs than in pushing companies to maximize their long-term value.” He concludes that maybe governments need to ‘force’ businesses to invest by “using regulatory, financial and tax policies to push businesses toward greater real investment”.

The trouble with this conclusion is that it fails to get to the heart of why US business investment growth has been declining. There is clear evidence provided by international agencies like the ECB, investment banks like JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs and by new mainstream economic studies that the main factor behind the gyration of business investment is profitability and profits.

For example, the EU Commission in a recent report noted that non-residential investment (which excludes households buying houses) as a share of GDP and the main reason was “a reduced level of profitability.” The EU report makes the key point that “measures of corporate profits tend to be closely correlated with investment growth” and only companies that don‘t need to borrow and are cash-rich can invest—and even they are reluctant. The Commission found that Europe‘s profitability “has stayed below pre-crisis levels.”

Similarly, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the central bankers’ association (and dominated by Austrian economics), believes that “the uncertainty about the economic outlook and expected profits play a key role in driving investment, while the effect of financing conditions is apparently small.” The BIS dismisses the consensus idea that the cause of low growth and poor investment is the lack of cheap financing from banks or the lack of central bank injections of credit. Instead, the BIS looks for what it calls a “seemingly more plausible explanation for slow growth in capital formation,” namely, “a lack of profitable investment opportunities.” According to the BIS, companies are finding that the returns from expanding their capital stock “won’t exceed the risk-adjusted cost of capital or the returns they may get from more liquid financial assets.” So they won‘t commit the bulk of their profits into tangible productive investment. “Even if they are relatively confident about future demand conditions, firms may be reluctant to invest if they believe that the returns on additional capital will be low.” Indeed.

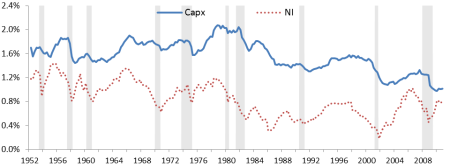

A recent empirical study by mainstream economists, Kothari, Lewellen and Warner find a close causal correlation between the movement in US business investment (Capx in graph below) and business profitability (NI in graph). As readers know from this blog and in other work by Marxist economists, the US non-financial corporate rate of profit fell secularly from the 1950s, reaching a low in the mid-1980s and then consolidating or rising a little after that. The mainstream authors find the same.

They also find that investment growth is highly predictable, up to 1½ years in advance, using past profits and stock returns but has little connection to interest rates, credit spreads, or stock volatility. Indeed, profits and stock returns swamp the predictive power of other variables proposed by others like Noah Smith. Profits show a clear business-cycle pattern and a clear correlation with investment. The data show that investment grows rapidly following high profits and stock returns—consistent with virtually any model of corporate investment—but can take up to a year and a half to fully adjust.

They conclude that “we find no evidence that investment drops following a spike in aggregate uncertainty, contrary to the predictions of many models with irreversible investment.” Finally, the authors found that “at least three-quarters of the investment decline in the Great Recession can be thought of as a historically typical drop given the behavior of profits. Problems in the credit markets may have played a role, but the impact on corporate investment is arguably small relative to a decline in investment opportunities.”

So all the alternative explanations of crises offered by monetarists, Keynesians and post-Keynesians have no empirical backing. The Marxist one of investment being driven by profitability does. This suggests that it is the profitability of capital that is decisive for the recovery or otherwise from an economic recession or depression. If that is the case, then trying to regulate or tax businesses may well reduce investment if it affects profitability. This suggests that there is no escape from the capitalist solution: a massive devaluation of the value of capital (both in means of production and the labour force) through an economic recession or slump.

No comments:

Post a Comment