In the first part of this double post, I dealt with whether Marx had a coherent theory of crises or not. I reckoned that Marx’s theory was based on his law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall and that this law was realistic and coherent. I also argued that Marx did not dispense with this law in his later works that some have claimed and it remains the best and most compelling theory of regular and recurrent economic crises in capitalism. In this second part, I shall provide some empirical evidence from modern capitalist economies to support this view. This completes what is really just a short essay on Marxist economic crisis theory – as I see it – with much left out.

Does Marx’s law fit the facts?

Some Marxist critics of Marx’s law of profitability reckon that the law cannot be empirically proven or refuted because official statistics cannot be used to show Marx’s law in operation. But there are plenty of studies by Marxist economists that show otherwise. The key tests of the validity of the law in modern capitalist economies would be to show whether 1) the rate of profit falls over time as the organic composition of capital rises; 2) the rate of profit rises when the organic composition falls or when the rate of surplus value rises faster than the organic composition of capital; 3) the rate of profit rises, if there is sharp fall in the organic composition of capital as in a slump. These would be the empirical tests and there is plenty of empirical evidence for the US and world economy to show that the answer is yes to all these questions.

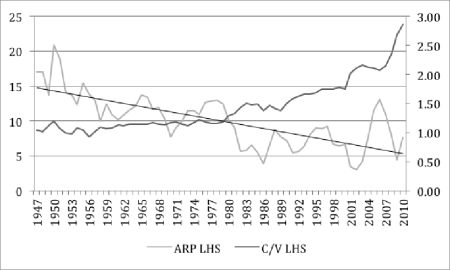

For example, Basu and Manolakos applied econometric analysis to the US economy between 1948 and 2007 and found that there was a secular tendency for the rate of profit to fall with a measurable decline of about 0.3 percent a year “after controlling for counter-tendencies.” In my work on the US rate of profit, I also found an average decline of 0.4 percent a year through 2009. And here is a figure by G Carchedi for the rise in the organic composition of capital (OCC) in the industrial sector of the US since 1947 versus the average rate of profit (ARP). It tells the same story.

US ARP and OCC (i.e. C/V)

There is a clear inverse correlation between a rising organic composition of capital and a falling rate of profit.

Can Marx’s law explain crises?

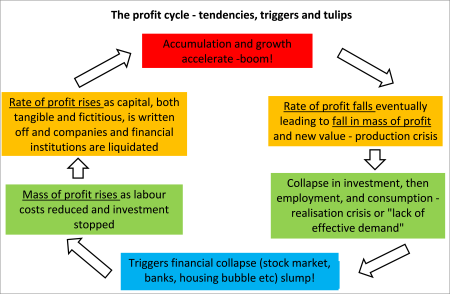

How does Marx’s law of profitability work as an explanation and forecast of slumps in capitalist economies? The law leads to a clear causal connection to regular and recurrent crises (slumps). It runs from falling profitability to falling profits to falling investment to falling employment and incomes. A bottom is reached when there is sufficient destruction of capital values (the writing off technology, the bankruptcy of companies, a reduction in wage costs) to raise profits and then profitability. Then rising profitability leads to rising investment again. The cycle of boom recommences and the whole ‘crap’ starts again, to use Marx’s colourful phrase. There is a cycle of profit alongside the long-term tendency for the rate of profit to fall.

The evidence of this causality between profit and investment is available. Jose Tapia Granados, using regression analysis, finds that, over 251 quarters of US economic activity from 1947, profits started declining long before investment did and that pre-tax profits can explain 44% of all movement in investment, while there is no evidence that investment can explain any movement in profits. I find a higher ‘Granger causality’ of 60% from annual changes in profit and investment (unpublished) and a correlation of 0.67 for the period since 2000. And see this by G Carchedi (Carchedi Presentation).

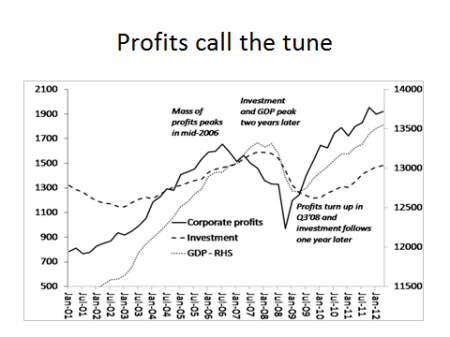

In the period leading up to the Great Recession 2008-9, we can see the causality visually for US profits, investment and real GDP in the graphic below. The mass of US corporate profit peaks in mid-2006, investment and GDP follows two years later. Profits turn back up in late 2008 and investment follows one year later.

There are two basic regularities shown by the data: that a change in profits tends to be followed next year by a change in investment in the same direction; and that a change in investment is usually followed in a few years by changes in profits in the opposite direction. Thus we have a cycle. From these results, the “regularity” of the business cycle, and the fact that profitability stagnated in 2013 and declined in 2014 (and now the mass of profits in 2015) after growing between 2008 and 2012, it can be concluded with some confidence that a recession of the US economy, which will be also part of a world economic crisis like the Great Recession, will occur again in the next few years.

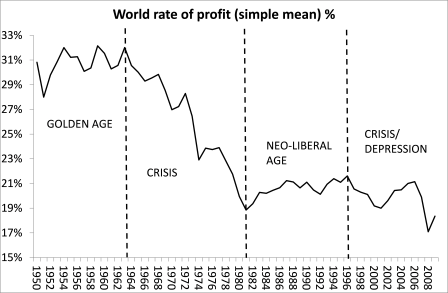

And Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall makes an even more fundamental prediction: that the capitalist mode of production will not be eternal, that it is transitory in the history of human social organisation. The law of the tendency predicts that, over time, there will be a fall in the rate of profit globally, delivering more crises of a devastating character. Work has been done by modern Marxist analysis that confirms that the world rate of profit has fallen over the last 150 years. See the graph below (data from Esteban Maito and ‘doctored’ by me).

Maito’s data for the 19th century have recently been questioned (DUMENIL-LEVY on MAITO), but in a recent work using different sources and countries, I find a similar trend for the post-1945 period globally (Revisiting a world rate of profit June 2015). And earlier groundbreaking work by Minqi Li and colleagues, as well as by Dave Zachariah, show a similar trend.

As Maito concludes: “The tendency of the rate of profit to fall and its empirical confirmation highlights the historically limited nature of capitalist production. If the rate of profit measures the vitality of the capitalist system, the logical conclusion is that it is getting closer to its endpoint. There are many ways that capital can attempt to overcome crises and regenerate constantly. Periodic crises are specific to the capitalist mode of production and allow, ultimately, a partial recovery of profitability. This is a characteristic aspect of capital and the cyclical nature of the capitalist economy. But the periodic nature of these crises has not stopped the downward trend of the rate of profit over the long term. So the arguments claiming that there is an inexhaustible capacity of capital to restore the rate of profit and its own vitality and which therefore considers the capitalist mode of production as a natural and a-historical phenomenon, are refuted by the empirical evidence.”

So the law predicts that, as the organic composition of capital rises globally, the rate of profit will fall despite counteracting factors and despite successive crises (which temporarily help to restore profitability). This shows that capital as a mode of production and social relations is transient. Capitalism has not always been here and it has ultimate limits, namely capital itself. It has a ‘use-by-date’. That is the essence of the law of profitability for Marx.

Alternative theories

This is not to deny other factors in capitalist crises. The role of credit is an important part of Marxist crisis theory and indeed, as the tendency of the rate of profit to fall engenders countertendencies, one of increasing importance is the expansion of credit and the switching of surplus value into investment in fictitious capital rather than productive capital to raise profitability temporarily, but with eventually disastrous consequences, as The Great Recession shows (The Great Recession; Debt matters).

Alternative theories of crisis like underconsumption, or the lack of effective demand, are taken from theories from the reactionary Thomas Malthus and the radical Sismondi in the early 19th century and then taken up by Keynes in the 1930s and by modern inequality theorists like Stiglitz and post-Keynesian economists. But lack of demand and rising inequality cannot explain the regularity of crises or predict the next one. These theories do not have strong empirical backing either (Does inequality causes crises).

Professor Heinrich, after concluding that Marx did not have a theory of crisis and dropped the law of profitability, does offer a vague one of his own: namely capital accumulates and produces more means of production blindly. This gets out of line with consumption demand from workers. So a ‘gap’ develops that has to be filled by credit, but somehow this cannot hold up things indefinitely and production then collapses. Well, it is a sort of a theory, but pretty much the same as the underconsumption (overproduction) theory that Heinrich himself dismisses and Marx dismissed 150 years ago. It seems way less convincing or empirically supported that Marx’s own theory of crisis based on the law of profitability.

No other theory, whether from mainstream economics or from heterodox economics, can explain recurrent and regular crises and offer a clear objective foundation for the transience of the capitalist system.

Why not Marx’s law of profitability?

Finally, why do Professor Heinrich and others like Professors David Harvey, Dumenil and Levy and many other Marxist economists, want to dish Marx’s law of profitability as a theory of crises?

Obviously, they think it is wrong. But all these alternative theories have one thing in common. They suggest a way out of crises within the capitalist system. If it’s due to underconsumption, then spend more by government; if it’s due to rising inequality; then correct that with taxation; if it’s too much credit or instability in the financial sector, then regulate it. None of these leads to policies or actions to replace the capitalist mode of production at all but merely to correct or improve it. They lead to reformist strategies i.e. there no need to replace the capitalist mode of production with common ownership of the means of production and democratically controlled planning for need (socialism).

Then socialism becomes a moral issue to end poverty and inequality not an objective necessity if human society is to achieve freedom from toil. That’s a reformist view, but not Marx’s. Actually even these small changes that preserve capitalism might still require revolutionary action in the face of fierce opposition by capital – so why stop at reform?

No comments:

Post a Comment