Back last summer, there was growing concern that the world economy, already making the weakest recovery from the deepest slump in production and investment since 1945, was slowing down.

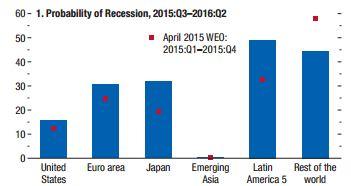

Indeed, it now seemed that the ugly thought of another recession, as economists call a contraction in production, incomes and spending, was a serious possibility within a few years or less. The IMF raised the probability of recession in the so-called ‘emerging economies’ of Latin America, ex-China Asia and the rest of the world to near 50%.

The slowdown in emerging economies has been led by the significant slowdown in China’s powerhouse economy, from double-digit real GDP growth just a few years ago to less than 7% now on the official figures (many ‘experts’ reckon real GDP growth is much lower than that). As China slowed, its inexorable demand for energy and other raw materials and other export goods from elsewhere dropped. Other large emerging economies plummeted into recession (Brazil, Russia, South Africa).

Indeed, as I have previously pointed out, before the crisis, world trade tended to grow around twice as quickly as world GDP, but since 2012 trade growth has simply matched that of GDP.

“The global economy is uncomfortably close to the edge,” said David Stockton, senior fellow at the right-wing mainstream Peterson Institute for International Economics. “Economics isn’t rocket science, and even rockets frequently land in the wrong place or explode in mid-air,” wrote Willem Buiter, chief global economist at Citigroup, who has assigned a 55% chance of a moderate to severe global contraction next year.

This worry even led the US Federal Reserve to delay its planned and much anticipated hike in its base interest rate that affects the cost of borrowing dollars in the US and globally. If the emerging economies were slumping, it would be the wrong time to dampen household spending and business investment.

However, the optimists among mainstream economics have dismissed these prognoses. Emerging economies may be slowing down and some may have contracted outright, but the major advanced economies were doing okay and Europe was actually picking up a little from its depression of 2010-13. So the global economic recession was not going to happen.

Well, now we are getting data for real economic growth for the third quarter of 2015 (June to September) from the major advanced economies – and it is not great news for the optimistic scenario. The slowdown in economic activity experienced in China and in most emerging economies is now being repeated in the advanced economies.

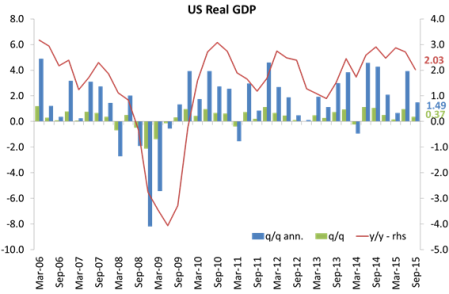

The US economy is the largest in the world and up to now has been recovering relatively better than the other major economies within Europe and Japan. In Q3, the US economy did expand but only at a 1.5% annualised pace, down from 3.9% in the second quarter. That meant that the US economy expanded in real terms over the last 12 months by just 2%, down from 2.7% in Q2.

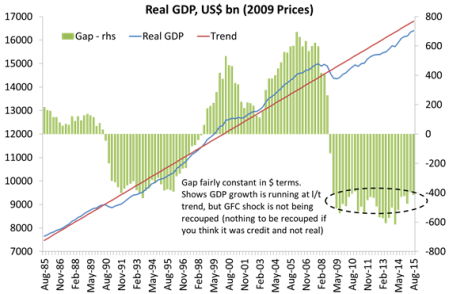

This 2% growth rate has become the norm for the US since the end of Great Recession. There seems no prospect of a return to previous trend growth and that means there has been a permanent loss of value for the American people from the Great Recession.

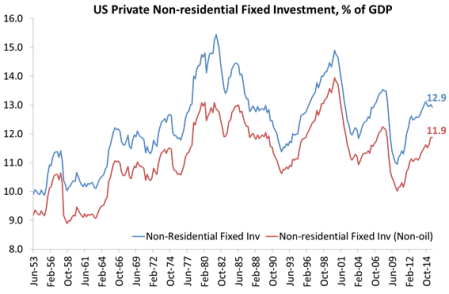

In Q3, US business investment slowed to its lowest yoy rate for over two years. Business investment grew more slowly, up only at an annual rate of 2.1% compared with 4.1% in Q2. Investment in new plant actually dropped 4% while investment in software and such rose at the slowest pace since 2013. And, as a share of GDP, investment remains below pre-crash levels.

Now, some have been arguing that business investment in things like plant, machinery and equipment is less necessary given the new ‘disruptive technologies’ of the internet of things, software, algorithms etc that do not require tangible structures. So investment is taking place but it now costs way less and is not really captured in the data.

For example, McKinsey argues that the “the US economy has shifted toward intellectual property–based businesses. Medical-device, pharmaceutical, and technology companies increased their share of corporate profits to 32 percent in 2014, from 13 percent in 1989. Since a company’s rate of growth and returns on capital determine how much it needs to invest, these and other high-return enterprises can invest less capital and still achieve the same profit growth as companies with lower returns”. McKinsey- US – Are share buybacks jeopardizing future growth

Or put it another way: “while capital spending has outpaced GDP growth by a small amount, investments in intellectual property— research and development—have increased much faster. In inflation-adjusted terms, investments in intellectual property have grown at more than double the rate of GDP growth, 5.4 percent year versus 2.4 percent. In 2014, these investments amounted to $690 billion.” So McKinsey concludes: “Certainly, some individual companies are probably spending too little on growth—just as others spend too much. But in aggregate, it’s hard to make a broad case for underinvestment”.

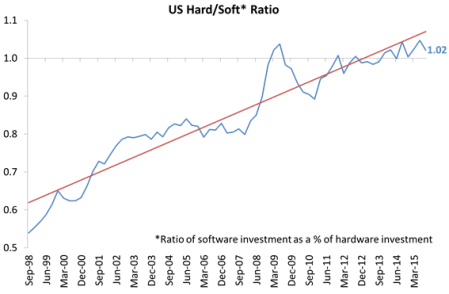

No doubt there is some truth in this. But even if investment is increasingly in ‘intellectual property’ and not in factories and robots (really?), even in the former, there appears to have been a slowdown in the US. Software investment is no longer outstripping investment in hardware.

US household spending did rise 3.2% in the quarter. The tax intake for personal incomes fell, so disposable personal income increased 4.8% compared with 3.4% in Q2. And with headline inflation near zero, real disposable personal income rose. That’s why household spending was up. But while it’s true that the US unemployment rate continues to fall, the pace of that improvement is waning.

The slowdown in US economic growth was also repeated in the UK, the only other major advanced economy that has experienced 2%-plus real GDP growth in the last year or so. Real GDP rose just 0.5% in the third quarter of 2015, so that real GDP is now 2.3% higher than this time last year, down from a growth rate of 2.4% yoy in Q2. Although UK real GDP is now 6.4% higher than its peak at the beginning of 2008 (before the Great Recession), nearly seven years ago, once the population increase (up 3m, partly from net immigration) is taken into account, real GDP per head has only just reached the 2008 level.

As in the US, UK growth was almost totally confined to ‘services’. Manufacturing and construction actually contracted. Within services, the main contribution came from property and finance, the ‘unproductive’ sectors of the economy.

Back in 2008, manufacturing was nearly 10% of GDP and real estate was 8.5%. Now manufacturing is 8.6% and real estate is 10.4%. Real estate has jumped over 20% since 2008 while manufacturing has contracted nearly 7%. Indeed, UK heavy industry like steel is being crushed by falling commodity prices, weak economic growth in Europe and the dumping of Chinese steel in world markets . That’s the nature of UK economic growth: unproductive and credit-fuelled.

As for the other G7 economies, the slowdown is even worse. Canada is in a ‘technical recession’, two consecutive quarters of contraction in real GDP.

Japan is teetering on a recession. And just today, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) lowered its forecast for real economic growth out to 2018. The BoJ now sees growth in the year to April 2016 at just 1.2%, down from 1.7%. For the year to March 2017, the BoJ now expects growth of 1.4% down from a 1.5% forecast in July. And for the year to March 2018, the BoJ forecasts growth of only 0.3%!

The other G7 economies are in the Eurozone. Germany has sustained a very modest growth rate in the last few years of about 1.0-1.5%; France has growth even less each year; and Italy has been stagnant (although it appears to be finally making a mild recovery in the couple of quarters). We shall know more when the Q3 GDP figures come out next week. But Germany is likely to record slower growth as exports to Asia and China have taken a tumble.

Spain has been the fastest-growing of the Eurozone economies in the last year or so, having suffered badly in the Great Recession with a housing collapse and a massive increase in unemployment. But the ‘boom’ since 2013 appears to be over. Today, the figures released for Q3 2015 real GDP growth showed a slowdown to 0.8% on the quarter compared with 1% in the previous quarter. The year on year rate was up to 3.4% though compared to 3.1% in Q2. But that could be it.

So expansion in the major advanced economies is slowing alongside the sharp drop in GDP growth in the emerging economies. Indeed, Taiwan, a key Asian industrial economy, has just announced that its real GDP in Q3 fell by 1% from a year earlier, the first contraction in six years.

Since World War II, recessions have occurred at regular intervals, between 6-10 years. The current expansion is more than six years old, beginning in July 2009. Mainstream economics has signally failed to predict them. For example, in the spring of 2001, the US economy faced weak growth abroad and the fallout of the dot-com bubble, but only 15% of economists surveyed that summer believed a downturn had begun. Yet the economy was in the midst of a recession that lasted nine months. As for the Great Recession, the failure of nearly all mainstream economists and major international institutions like the IMF and the OECD to see this major slump coming is well recorded. (The causes of the Great Recession).

The next recession will pose big problems for the economic policy makers of the major countries. Easy monetary policy (zero interest rates, quantitative easing) has been virtually exhausted (apart from being pretty ineffective anyway in boosting the ‘real economy’ rather than stock markets and banks). Keynesian-style government spending has been rejected or curbed up to now because public sector debt levels have been so high and corporate profitability has been so low.

There are those like Ben Bernanke, former Fed chief or Andy Haldane, current chief economist at the Bank of England, who argue that central banks saved the major economies from a Great Depression and there is even more that can be done in printing money for direct handouts to households or having negative interest rates to avoid a new slump.

And the Keynesians like Paul Krugman, Larry Summers, Simon Wren-Lewis and a host of others continue to push for more government spending and budget deficits to ‘pump-prime’ the economy. But this is more likely to reduce profitability and investment of the capitalist sector than save it.

The next recession cannot be avoided and it is not far away.

No comments:

Post a Comment