So Justin, the son of the former Liberal PM of the 1970s, Pierre Trudeau, has triumphed in Canada’s general election. The Liberal party came from behind to sweep into an outright majority victory, removing the incumbent Conservative government that had been in office for nearly ten years under Stephen Harper.

The third party, the New Democrats, similar to the British Labour party, which had been ahead in the polls at the start of the long 79-day election campaign, eventually fell back to a poor third. The reason, it seems, is that the Liberals decided to adopt an anti-austerity programme, advocating budget deficits (not large though), improved minimum wages and an infrastructure investment plan, in opposition to the neo-liberal polices of the Conservatives. The Liberals stole the NDP policies and romped to victory.

Justin Trudeau though faces a difficult task economically. Canadian capitalism has been a relative success story, based on its close proximity to US imperialism and its capital investment and its resources of oil, gas and other minerals. But that ‘luck’ also delivers big vulnerabilities: the economy is subject to the swings of boom and slump in the US and to changes in the world prices for oil and resources.

And world energy prices have plummeted in the last 18 months. As a result, the Canadian dollar has plummeted from parity with the US dollar to some 30% weaker. And the economy has slipped into a ‘technical recession’, where real GDP has contracted for two successive quarters.

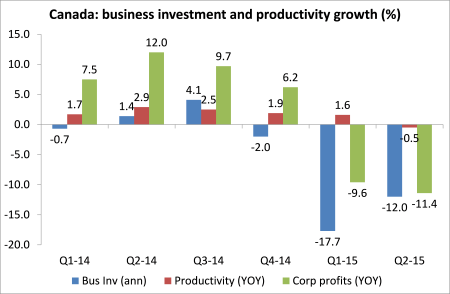

Behind that lies a collapse in business investment, mainly in the energy sectors. In June, there was a 4.6% fall. As the IMF put it “Business nonresidential investment has slowed in recent years (following a strong rebound initially after the crisis). The slowdown has been widespread— including both the energy sector and broader spending on machinery and equipment”. cr1522

And as the Royal Bank of Canada puts it: “Business fixed investment fell at double-digit rates in both the first and second quarters of 2015 weighed down by massive cuts by energy companies. The persistence of low oil prices (WTI hit a cycle low in late August) will likely yield another hit to investment in the third and potentially fourth quarters. Despite large cuts introduced earlier in the year, the recent downdraft in energy prices and our revised assumption that the rebound in 2016 will be more muted than we previously thought, suggests that investment by the energy sector will continue to decline in 2016.” fcst_sep2015

The only thing keeping the economy going is credit-fuelled, low interest borrowing, boosting consumption and a housing bubble. The Bank of Canada has commented that the housing bubble will “increase the likelihood and potential severity of a correction later on”. Canada’s household debt-to-disposable income ratio stood at a record 164.6 in the second quarter of 2015, compared with 163.0 in the first quarter, according to the national statistics agency. It has risen from 142.52 per cent in the first quarter of 2008, the year of the financial crisis.

The Royal Bank of Canada’s affordability index for housing has reached 60% in Toronto, the highest it has been since the early 1990s. Vancouver is ranked at more than 80%, the highest since 1982 when it exceeded 90%. If interest rates start rising, this will drive up debt servicing for many.

Interest rates and business investment are low not just because of the collapse in energy prices. Canadian business profitability has been weak and falling. Productivity growth has been poor.

As the IMF put it in a recent report: “Perceived low investment profitability has negatively affected the neutral rate. After a quick turnaround at the end of the recession, labor productivity and, especially, the investment specific shock (which drives investment profitability) have been underperforming until recently, reducing the demand for funds and, thus, preventing the natural rate from rising. In particular, news shocks to investment profitability turned particularly overly pessimistic by the end of 2011 even though labor productivity has been slowly improving.” cr1523

Indeed, the trajectory for profitability for Canadian capital over the long term has been similar to that of the US: the profitability crisis of the 1970s, followed by a neo-liberal recovery and then a downward shift before the Great Recession.

The recovery since the end of the Great Recession in mid-2009 looked promising as commodity prices, particularly energy, jumped. But, like Brazil, with the collapse in the ‘commodity cycle’, Canada’s recovery petered out and began to reverse. Now the new Liberal government is faced with weak or non-existent economic growth, businesses unable or unwilling to invest, and a risky housing bubble. Meanwhile, the global economy continues to slow.

No comments:

Post a Comment