The productivity of labour is an important ingredient of the rate of real GDP growth. What happens to productivity (output per worker or output per worker per hour) is important for mature capitalist economies because real GDP growth can be considered as made up of two components: productivity growth and employment growth. The first shows the change in new value per worker employed and second shows the number of extra workers employed.

In mature economies, employment growth has been slowing for decades. So faster productivity growth is necessary to compensate. In Marxist terms, that means slowing growth in absolute value (and surplus value) must be replaced by faster growth in relative new value (or surplus value). See my post,

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/01/20/productivity-deflation-and-depression/.

In the first quarter of 2015, US productivity fell at a 3.1% annual rate. For all of 2014, productivity grew by a modest 0.7%, even less than the 0.9% productivity gain in 2013. From 1995 to 2000, US productivity rose at average annual rates of 2.8%, reflecting in part the boost the economy received from the internet boom. But since 2000, productivity has slowed to annual rates of 2.1%.

The productivity slowdown is being replicated in all the major economies. The US Conference Board, which follows productivity growth closely, found that global labour productivity growth, measured as the average change in output (GDP) per person employed, remained stuck at 2.1% in 2014, while showing no sign of strengthening to its pre-crisis average of 2.6% (1999-2006).

The Conference Board reckons that the lack of improvement in global productivity growth in 2014 is due to several factors, including a dramatic weakening of productivity growth in the US and Japan, a longer-term productivity slowdown in China, an almost total collapse in productivity in Latin America, and substantive weakening in Russia.

Labour productivity in the mature capitalist economies grew by only 0.6% in 2014, slightly down from 2013 when it was 0.8%. Productivity growth in the US declined from 1.2% in 2013 to 0.7% quoted above in 2014, whereas Japan’s fell even more from a feeble 1% to negative territory of -0.6%. The Euro area saw a very small improvement in productivity —from 0.2% in 2013 to 0.3% in 2014.

For 2015, a further weakening in productivity is projected, down to 2%, continuing a longer-term downward trend which started around 2005. Despite a small improvement in the productivity growth performance in mature economies (up to 0.8% in 2015 from 0.6% in 2014), emerging and developing economies are expected to see a fairly large slowdown in growth from 3.4% in 2014 to 2.9% in 2015. The decline is primarily a reflection of the continuing fall in growth and productivity in China, but also includes the negative growth rate of Brazilian and Russian productivity

In the US, the ECRI, an economic research agency, argues that: “With productivity growth and potential labour force growth both averaging ½% a year, trend real GDP growth is converging to 1% a year.”

The ECRI goes on: “Recoveries have been weakening due to declines in growth in output per hour (i.e., productivity), growth in hours worked, or both. Taken together, they add up to real GDP growth. It’s just simple math….So, unless there’s good reason to believe that productivity growth will revive, trend GDP growth may very well stay stuck in the 1% range for years to come. If so, growth slowdowns could much more easily push growth below zero, leaving very little room for error. Is the Fed ready?”

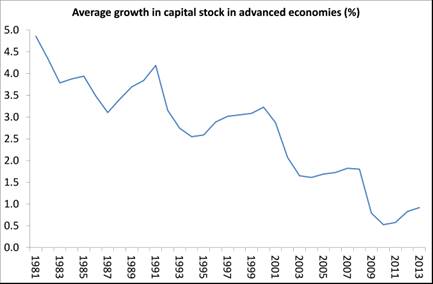

What the productivity growth figures show is that the ability of capitalism (or at least the advanced capitalist economies) to generate better productivity is waning. Thus capitalists have squeezed the share of new value going to labour and raised the profit share to compensate. But above all, they have cut back on the rate of capital accumulation in the ‘real economy’, increasingly trying to find extra profit in financial and property speculation. Look at the growth in the accumulated stock of capital in the advanced capitalist economies. This is a measure of the level of productive investment – it’s grinding to a halt.

Take the UK. British real economic output is only about 3% higher than at the beginning of 2008. Yet labour input (hours worked adjusted for schooling and experience) is up 11% and the real value of the UK’s net capital stock has grown only 6%. So underlying productivity has plunged in the last seven years.

A recent paper by the National Institute of Economic & Social Research (NIESR) suggests that the UK’s productivity fall may be due to widespread weakness in TFP within firms. And that seems to be because British companies prefer to employ cheap and temporary labour rather than invest in training to raise skills and utilise new technology. This goes back to the ‘hand car wash’ argument, where cheap labour means that firms don’t need to invest in equipment. Instead new and existing firms just find ways of profiting from the ready supply of cheap labour.

Indeed, a recent IMF paper concluded that labour market ‘deregulation’ (part-time, zero hours contracts, temporary, easy hire and fire etc), introduced as part of neo-liberal policies over the last few decades, may have raised profits but has done nothing to improve productivity and might even have made it worse.

An important debate is taking place inside the US Federal Reserve on the reasons for this slowdown. John Fernald, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, has argued that the slowdown started before the financial crisis and was associated with the end of the information-technology driven boom of the 1990s. David Wilcox, director of the Federal Reserve Board’s research and statistics division, argued with colleagues in a 2013 paper that the slowdown was associated with the 2007-2009 recession and a drop-off in new business formation and in productivity-enhancing investment by firms.

The Wilcox story is the more hopeful one. If the productivity slowdown is associated with the recession, then presumably its effects will eventually wear off and growth can get back on a faster path without causing inflation. The Fernald story is troubling. If productivity was really in a downtrend before the crisis, then Americans might be stuck with an economy prone to serial growth disappointments for the foreseeable future.

Now it has been countered by some mainstream economists that productivity growth is not being captured properly in the data. Capital investment growth is not really declining in the major economies. Much of the apparent slowdown only reflects lower relative prices of investment goods compared to consumer goods and services.

In the US, over the past two decades, prices of equipment have risen much less than the GDP deflator. When correcting for this price effect, the fall in US non-residential investment to GDP ratios is much less pronounced. The phenomenon is even more noticeable in IT investment. If IT prices had risen at the same rate as overall prices, IT investment would now be nearly 1.2% of GDP higher than recorded, putting US total investment closer to 20% of GDP, levels last achieved back in the 1990s.

So the argument goes; you only have to look around to see that technological advance is making lives easier and quicker; and within companies, productivity-enhancing innovatory technology is taking place at an accelerating pace. The age of artificial intelligence is fast coming. And it’s just this sort of investment that is low in cost and requires a low threshold to deliver increased productivity.

Over the last 20 years, capex has been increasingly going into hi-tech, R&D and cost-saving equipment and less so into ‘structures’, long-term investment in plant and offices. In 1995, R&D was 23% of US business investment and structures were 21%. Now the R&D share is 31% and structures are unchanged.

Neoclassical economics likes to use a measure of productivity called total factor productivity (TFP). This supposedly measures the productivity achieved from innovations. Actually, it is just a residual from the gap between real GDP growth and the productivity of labour and ‘capital’ inputs. So it is really a rather bogus figure. But the argument goes; maybe capex (investment) may have been growing slower, but ‘capital productivity’ has been rising because that enigmatic component, total factor productivity, has been rising, even if the data on investment growth show a slowdown.

The trouble with this argument is that the data on TFP do not show any sort of pick-up that would be expected from the great new IT revolution that is under way. The latest Conference Board data show that the growth rate of global TFP continues to hover around zero for the third year in a row, compared to an average rate of more than 1% from 1999-2006 and 0.5% from 2007-2012. Indeed, most mature economies show near zero or even negative TFP growth. In China, TFP growth has turned negative and in India it is just above zero, while in Brazil and Mexico TFP growth continues to be negative.

So it is more likely that productivity growth has really slowed because the impact of innovations is still not enough to compensate for the failure of capitalists in most economies to step up investment. Indeed, it is not the pure technology of the Internet and ICT by itself which increases productivity and economic growth. Nobel Economics Prize winner Robert Solow already noted in a famous phrase in 1987, six years after the beginning of the mass introduction of personal computers into the economy, that computer technology was not speeding up US productivity growth: ‘You see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.’

This has not changed. In 1980, the year before introduction of the modern personal computer, US annual TFP growth was 1.2% (5yr rolling average). By 2014, US TFP was still only 1.2%. Therefore 34 years of revolutionary technological developments in the Internet and ICT had led to no increase in US productivity! The data therefore clearly shows that technological advance in the internet and ICT sector alone do not lead to productivity increases.

There was one phase during the 34 years of the internet and ICT revolution when US economic efficiency sharply increased. In the period leading to 2003, US annual productivity growth reached its highest level in half a century – 3.6%. This was explained by a huge surge in ICT-focused fixed investment. US investment rose from 19.8% of GDP in 1991 to 23.1% of GDP in 2000, fell slightly after the ‘dot com’ bubble’s collapse and then reached 22.9% in 2005. The majority of this investment was in ICT. After this, US investment fell, leading to the sharp productivity slowdown.

The way in which US labour productivity followed this surge in capital investment is clear from the chart. The correlation between the growth in investment and the increase in labour productivity three years later was 0.86, and after four years 0.89 – extraordinarily high. When capital investment fell, this was followed by a decline in labour productivity – showing clearly it was not ideas or pure

technology that had caused the productivity increase.

In other words, productivity growth still depends on capital investment being large enough. And that depends on the profitability of investment. As argued ad nauseam in this blog: there is still relatively low profitability and a continued overhang of debt, particularly corporate debt, in not just the major economies, but also in the emerging capitalist economies (see

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/09/30/debt-deleveraging-and-depression/; https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/12/04/cash-hoarding-profitability-and-debt/).

Under capitalism, until profitability is restored sufficiently and debt reduced (and both work together), the productivity benefits of the new ‘disruptive technologies’ (as the jargon goes) of robots, AI, ‘big data’ 3D printing etc will not deliver a sustained revival in productivity growth and thus real GDP.

No comments:

Post a Comment