After the market turmoil last week, global stock markets have quietened down for now, although by most measures of stock price against corporate profits or earnings, stock markets are still ‘overvalued’. Take one of the most perceptive measures, the ratio of the stock market value of the major companies in the US (S&P-500) versus previously booked profits (‘trailing earnings’ reported), i.e. the price to earnings ratio. If we adjust that ratio for inflation and average it on a ten-year rolling basis, then the ratio is around 23, or some 25-30% above the historic average (see graph below).

So the stock market crash may have another leg yet. That would be especially likely if the US Federal Reserve finally carries through its plan to hike its basic interest rate for the first time since the Great Recession began back in early 2008. This basic rate is virtually zero and the Fed has added to zero rates and series of quantitative easing (QE) programmes over the past few years (printing money and buying government and mortgage bonds) to try and boost the economy and restore the banking system. QE did the latter but failed to do the former. Stephen Williamson,vice-president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, just issued a study in which he concludes : “There is no work, to my knowledge, that establishes a link from QE to the ultimate goals of the Fed – inflation and real economic activity. Indeed casual evidence suggests that QE has been ineffective.”

But until the stock market crash and the China slowdown, the Fed had been becoming confident that the US economy was recovering with GDP growth up and unemployment down. It was getting ready to hike its interest rate. The basic rate sets the rates for all others, like mortgages and loans to corporations.

The US second quarter real GDP figures were revised up last week. Now the stats say US real GDP rose 0.9% in Q2 instead of just 0.6% over Q1. That means the US economy was now 2.7% larger in 2015 so far than in 2014 at the same time. That’s not bad compared to growth in the other major capitalist economies, although it is still below the long-term average for the US of 3.3% a year and well below rates of growth usually achieved in the ‘recovery’ period from a recession.

The Fed sees reasonably strong growth in the US, but weak growth everywhere else. So the monetary policy committee of the Fed, which meets on 17 September, is in a dilemma. Should it start to raise rates in order to ‘curb’ any possible future inflation as labour markets get too ‘tight’ and also restore control of credit markets; or should it wait until the rest of the world catches up or stops sliding back?

Every year at the end of August, central bankers of the world meet in Jackson Hole, Wyoming for a series of seminars on the state of the world economy, the latest economic theory and monetary policy (in the afternoons the bankers take hikes up the mountains of the Grand Tetons for philosophical meditation). At Jackson Hole, eminent mainstream economists present papers to the bankers for discussion. Last weekend, the subject of the seminars was Inflation dynamics and monetary policy.

This time, the head of the Fed, Janet Yellen, was not present and neither was the ECB chief, Mario Draghi. So the keynote speech was delivered by Fed deputy chair, Stanley Fischer (Fed Official Fischer Leaves Door Open for September Rate Increase).

Fischer was all over the place. On the one hand, he said that the Fed was preparing to raise interest rates soon because of the “impressive” growth of the domestic economy. On the other hand, he suggested that the recent volatility of global financial markets could cause the Fed to hesitate, but only if it persisted. “We haven’t made a decision yet, and I don’t think we should,….We’ve got time to wait and see” (well, only two weeks!). Some amount of uncertainty is inevitable. “When the case is overwhelming, if you wait that long,” he said, “then you’ve waited too long.”(!). “The change in the circumstances which began with the Chinese devaluation is relatively new and we’re still watching how it unfolds, so I wouldn’t want to go ahead and decide right now what the case is — more compelling, less compelling etc,” So Fischer sums up: “”The economy is returning to normal. We’re not certain we are there yet.”

Make that of what you will. The Fed seems to have no idea what to do. The UK’s Bank of England has been even worse than the Fed in forecasting what would happen to the UK economy. And on whether to hike rates, it is even more confused. The UK economy has also been growing faster than most other major economies (although whether that is sustainable is doubtful). Inflation is near zero (although there is some underlying pick-up coming). But the UK is much smaller economy than the US and more subject to the weakness of growth in the Eurozone and China than America. So that should weigh on any decision to hike in the UK.

But Mark Carney, the useless (and very expensive) BoE governor seems to have no idea what to do. “Realisation of some of a downside risk previously identified by the MPC, if it persists, has to be weighed against ongoing domestic strength, underpinned by credible policy regimes and an increasingly robust financial system,” Carney argued. As usual with Britain, the BoE will wait to see what America does.

And there is no doubt that,outside the US and possibly the UK, there is little sign of economic recovery. On the contrary, things are getting worse. According to the OECD, economic growth in the 34 major advanced capitalist economies grew by only 0.4% in the second quarter of 2015 from the first quarter – a deceleration from the 0.5 per cent quarter-on-quarter growth achieved in the first three months of this year. Of the world’s seven major economies, the UK was the fastest growing in the second quarter, achieving 0.7 per cent expansion. The US took second place with 0.6 per cent. Other developed economies did not do so well in Q2, with a 0.4 per cent economic contraction in Japan, a 0.2 per cent contraction in Italy and flat-lining growth in France. Year-on-year GDP growth for the OECD area remained unchanged at 2 per cent in the second quarter of 2015.

Last week, the US credit rating firm Moody’s cut its 2016 global economic growth forecast just ten days after its last forecast. It put average growth in the top G20 world economies at 2.8 percent on average, versus the 3 percent it had forecast previously. It even revised down the US for next year: “We have revised our U.S. 2016 forecast down slightly as the negative impact of the stronger dollar seems more pronounced than we assumed previously,” it said cutting it to 2.6 percent from 2.8 percent.

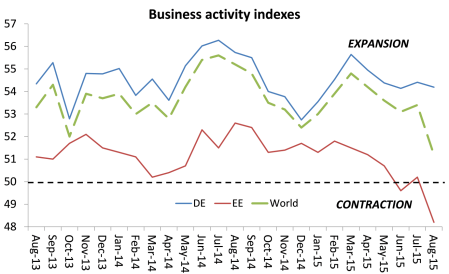

My own latest estimate of global PMI, an average of the monthly business activity indexes for national economies, shows that, in August, emerging economies have entered contraction territory, dragging world business activity down to a two-year low. World business is still growing overall (index above 50), but a significant slowdown has appeared in the summer (of the northern hemisphere).

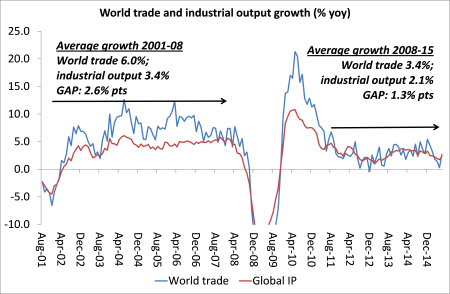

Most worrying of all is the state of world trade. The World Trade Monitor reports that world trade suffered its biggest fall in the six years since the financial crisis in the first half of this year. Much of this year’s slowdown in global trade has been due to a halting recovery in Europe as well as a slowing economy in China. The graph below compares world trade growth with industrial output growth. Usually world trade grows much faster than industrial output so that national economies can gain from exporting if their domestic economy is weak. But for the first time in 15 years, for several quarters in 2014, trade has grown more slowly than industrial output globally. And the gap in trade growth and industrial growth has narrowed sharply since the Great Recession.

Mainstream economics is divided about whether it is a good idea for the Fed and the BoE to start to raise rates or not. The Keynesians like Larry Summers and Paul Krugman reckon it would seriously damage consumer spending and investment and cause another credit crunch. They would prefer to keep the credit bubble going with cheap money forever, along with some more government spending on infrastructure etc, to avoid ‘secular stagnation’. Summers wrote that “a reasonable assessment of current conditions suggest that raising rates in the near future would be a serious error”.

On the other hand, the Austrian school of economics as represented by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), reckon that to keep fuelling the credit bubble with cheap money and QE is presaging yet another financial crash down the road as debt in all the major economies is still too high. Credit bubbles lead to ‘malinvestment’ and low productivity. It is better to keep government spending curbed and to hike rates so that money is not spend on useless projects and the credit bubble is ‘pricked’.

In its annual report and raised fears that unending printing of money and credit injections was creating financial and property asset ‘bubbles’ that would eventually burst and renew the financial crash of 2008. Jaime Caruana, head of the BIS, said the international system “is in many ways more fragile than it was in the build-up to the Lehman crisis”.

Both sides are probably right and wrong. The Keynesians are probably right that tightening monetary policy when inflation is low and global growth is weak could well trigger another stock market crash. But they are wrong to ignore the dangers of ‘permanent’ credit bubbles and high debt in causing crashes too (after all, what about the global financial crash of 2007). The Austerians (Austrians) are right that permanent credit bubbles are ‘unproductive’ and risk financial crashes, but they are wrong to think that cutting government spending and making borrowing costs higher when investment and growth is so low would not also risk a new recession.

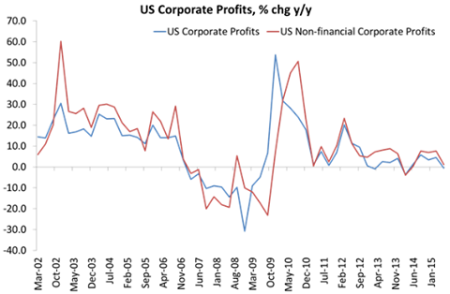

What both sides never consider is why economic growth, investment and prices are so low. They ignore the role of profitability in capitalist economies – although it is self-evident really that capitalism wont ‘recover’ unless profitability does. Globally, that has not happened in the major economies, with the exception possibly of the US. And even there, profitability is still below the peak of the late 1990s. In 2014, US profitability hardly moved and now growth in the mass of US profits (not the rate) is slowing to a trickle. Last week along with the revised GDP figures, the date for corporate profits in Q2 2015 were released. Profits were up slightly on the quarter but are nearly 2% down on this time last year.

The slowdown in profits in the US is mirrored in China too, where industrial profits are now contracting.

And if we look at global corporate profits (five major economies as compiled by me), there is little growth at all.

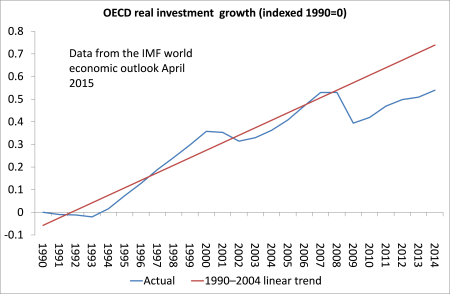

When profit growth slows, investment slows. When profits fall, investment follows (I recently estimated that for the US, the correlation between changes in the rate of profit and investment was 64%; second, the correlation between the mass of profit and investment was 76%; and third, the correlation between the rate of profit (lagged one year) and the mass of profit was also 76%.) The Great Recession saw a significant fall in investment, much more than consumption. Since the end of the Great Recession and in the ‘recovery’ investment growth has remained well behind trend in the major economies.

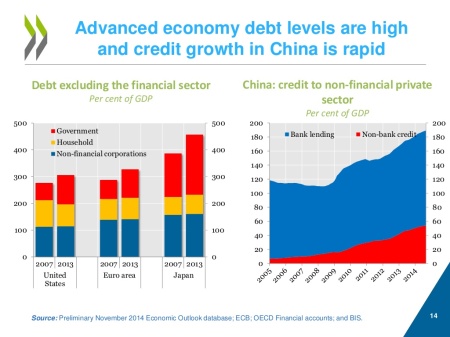

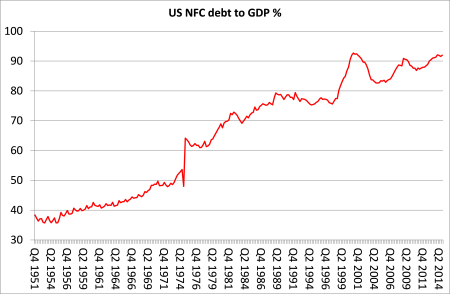

At the same time, the overall debt burden for the major economies has increased.

And most important, corporate debt is still on the rise (partly because of cheap money and low rates for borrowing). If profits start to fall that will put an extra burden on debt servicing for companies.

So if the Fed hikes rates in September or later, it is likely to increase the risk of a new stock market slide and more important a new slump, something that I have warned about before. Getting out of the Jackson Hole won’t be easy.

No comments:

Post a Comment