So Greeks have voted NO by a significant majority in the referendum on the Troika conditions for bailout funds to repay Greek government debt. Given the scare tactics of the EU Commission and the German politicians, the might of Greek pro-capitalist media noise and the closure of the banks making it difficult, if not impossible, to conduct daily business, the majority ‘no vote’ is a huge defeat for the Troika and big capital in Europe; and a victory for the Greek people and European labour.

But, in a way, the result of the Greek referendum does not make any difference to dealing with the problems ahead. Tsipras and Varoufakis say that the vote will now enable them to negotiate a better deal with the Troika for a new bailout package that will, they hope, include some ‘debt relief’.

But that assumes the Troika will be prepared to negotiate at all with Syriza.

Look at this comment from German economy minister Sigmar Gabriel (a social democrat!) who told the Tagesspiegel newspaper that this no vote makes it hard to imagine talks on a new bailout programme with Greece. And he accused Alexis Tsipras of having “torn down the last bridges” which could have led to a compromise: “With the rejection of the rules of the euro zone …negotiations about a programme worth billions are barely conceivable,….Tsipras and his government are leading the Greek people on a path of bitter abandonment and hopelessness.”

Even if they do, they may not offer any better conditions. Remember, Syriza had already agreed to raising social security contributions and VAT, to reducing pensions over time and to privatisations across the board (see my post https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/04/28/greece-crossing-the-red-lines/).

To quote Larry Elliot in the Guardian: “Greece’s membership of the euro hangs by a gossamer thread after the victory for the no side in the country’s referendum. The cash machines are running out of money and the economy is in freefall. The fate of the home of democracy is not in its own hands. If it chooses to do so, the European Central Bank could force Athens to default on its debts and issue its own currency on Monday morning by withdrawing emergency support for the Greek banking system.”

And “Whether they will do so remains to be seen. Indeed, the relentless mishandling of Greece ever since the crisis first flared up in 2010 suggests that blunder will follow blunder. It doesn’t help that relations between Greece and the other 18 members of the euro zone are now so sour. The chances of Greece leaving the euro by mistake, just as Lehman Brothers went bust by mistake in 2008, are reasonably high.”

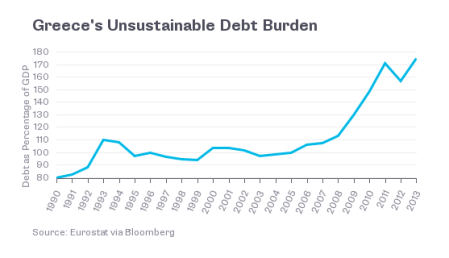

But longer term, the real issue is that Greece’s public and private debt burden is just too large for the Greek capitalist economy to service, despite already squeezing Greek labour to the death – literally. The Greek public debt burden arose for two main reasons. Greek capitalism was so weak in the 1990s and the profitability of productive investment was so low, that Greek capitalists needed the Greek state to subsidise them through low taxes and exemptions and handouts to favoured Greek oligarchs. In return, Greek politicians got all the perks and tips that made them wealthy too.

This weak and corrupt Greek economy then joined the euro and the gravy train of EU funding was made available and German and French came along to buy up Greek companies and allow the government to borrow and spend. The annual budget deficits and public debt rocketed under successive conservative and social democratic governments. These were financed by bond markets because German and French capital invested in Greek businesses and bought Greek government bonds that delivered a much better interest than their own. So Greek capitalism lived off the credit-fuelled boom of the 2000s that hid its real weaknesss.

But then came the global financial crash and the Great Recession. The Eurozone headed into slump and Eurozone banks and companies got into deep trouble. Suddenly a government with 120% of GDP debt and running a 15% of GDP annual deficit was no longer able to finance itself from the market and needed a ‘bailout’ from the rest of Europe.

But the bailout was not to help Greeks maintain the living standards and preserve public services during the slump. On the contrary, living standards and public services had to be cut to ensure that German and French banks got their bond money back and foreign investment in Greek industry was protected.

When it was suggested that German and French banks should take the hit, the ECB president at the time of the first bailout, Trichet responded that this would cause a banking meltdown as Lehman’s had done in the US in 2008. He “blew up,” according to one attendee. “Trichet said, ‘We are an economic and monetary union, and there must be no debt restructuring!’” this person recalled. “He was shouting.” By this, he meant no losses for the banks as ‘reckless creditors’, instead the Greeks must take the full burden as the ‘reckless borrowers’.

So through the bailout programmes, foreign capital was more or less repaid in full, with the debt burden shifted onto the books of the Greek government, the Euro institutions and the IMF – in other words, taxpayers. Greece was ultimately committed to meeting the costs of the reckless failure of Greek and Eurozone capital.

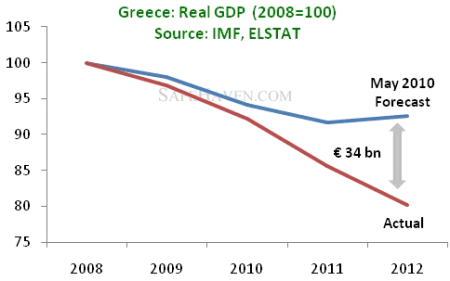

The Troika’s plan was to make the Greeks pay at the expense of a 25% fall in GDP, a 40% drop in real incomes and pensions and 27% unemployment rate. The government deficit was turned into a ‘primary surplus’ within the shortest period of time by any modern government. Greece has reduced its fiscal deficit from 15.6 percent of GDP in 2009 to 2.5 percent in 2014, a scale of deficit reduction not seen anywhere else in the world. Total public sector employment declined from 907,351 in 2009 to 651,717 in 2014, a decline of over 255,000. That is a drop of over 25%. Greece has gone from one of the lowest average retirement ages to one of the highest. In this sense, Greece had undertaken the most significant pension reform in Europe even before the latest demands of the Troika. This was austerity at its finest.

But the horrible irony is that this policy failed. Far from recovering, the Greek capitalist economy went into a deep depression. The supposed export-led economic recovery did not materialise. Instead the austerity measures have only made things worse.

So whatever the vote in the referendum, Greece cannot pay back the public sector debt, 75% of which is owed to the Troika of the Eurozone loan institution (EFSF) , the IMF and the ECB. And with the banks closed and credit withdrwan by the EB and the rest of European capital, the economy is in meltdown.

That the debt cannot be repaid is now openly admitted by the IMF in its latest debt sustainability report on Greece (here). The IMF now recognises that it got its forecasts of recovery hopelessly wrong.

Now, in its new report, the IMF reckons that the creditors must write off debt equivalent to at least 30% of Greek GDP to even begin to be able to sustain its debt servicing without default. As it puts it, “It is unlikely that Greece will be able to close its financing gaps from the markets on terms consistent with debt sustainability. The central issue is that public debt cannot migrate back onto the balance sheet of the private sector at rates consistent with debt sustainability, until debt-to-GDP is much lower with correspondingly lower risk premia”. Of course, any write-off must be on loans already made by the Euro Group. The IMF and ECB still expect to paid back in full!

Why cannot the debt on the Greek government books be serviced and repaid in full? It’s very simple. The Greek capitalist economy is just too weak, too inefficient and too unproductive to grow fast enough. Greek wages have been slashed, public sector spending has been cut savagely, pensions have been reduced sharply. Plans to improve tax collection and end avoidance and evasion are being put in place. But by IMF estimates, tax revenues will still not be enough to deliver a sufficiently large surplus before interest payments on existing debt for Greece to pay down its debt. Indeed, the IMF estimates are probably way too optimistic and the level of debt haircuts on the Euro institutions should be much higher than the IMF estimates.

So if the Syriza government or any other Greek combination government is forced into a new ‘bailout’ package in order to try and get the government to service its debt, the Alice in Wonderland scenario of more loans to pay for previous ones will continue – a true Ponzi scheme The more austerity and cuts in living standards are applied, the more difficult it will be for Greek capitalism to grow.

Whether there is now a deal with the Troika or alternatively, Grexit, the Greek economy needs to grow. Onlty this can make any public or private debt burden disappear. Take the US. The US public sector debt is huge at nearly 100% of GDP. But the US can service that debt easily because it has nominal GDP growth of just 4% a year. And the interest costs on its debt are very low at just 3% a year. As growth is higher than the interest cost on the debt, the US government can run a deficit of taxes versus spending (before interest) of 1% of GDP a year, and its debt ratio will still stay stable (but not fall).

Greece, on the other hand, in 2011, had interest costs of over 4% on its debt and nominal GDP of -5% a year, so it needed a government surplus of 9% of GDP just to keep the debt from rising. The government was applying austerity but still a deficit. Even the small debt restructuring of 2012 in the second bailout program did not stop the rise in the debt ratio. It is still rising.

In the 2012 bailout package, the Euro group agreed to put off repayment of its loans until 2022 and reduce the interest payments on them to just 2%. So, to stabilise the debt, the Greek economy now needs to grow by only 2% a year in nominal terms and balance its budget. But it cannot even do that yet. And even if it could, that would mean the debt ratio would just remain at 180% of a still contracting Greek GDP. So everything depends on restoring growth, much faster growth. That means more investment, new jobs, rising incomes and tax revenues and the ability to pay debt.

How can the Greek economy be made to grow? There are three possible economic policy solutions. There is the neoliberal solution currently being demanded and imposed by the Troika. This is to keep cutting back the public sector and its costs, to keep labour incomes down and to make pensioners and others pay more. This is aimed at raising the profitability of Greek capital and with extra foreign investment, restore the economy. At the same time, it is hoped that the Eurozone economy will start to grow strongly and so help Greece, as a rising tide raises all boats. So far, this policy solution has been a signal failure. Profitability has only improved marginally and Eurozone economic growth remains dismal.

The next solution is the Keynesian one. This means boosting public spending to increase demand, introducing a cancellation of part of the government debt and leaving the euro to introduce a new currency (drachma) that is devalued by as much as is necessary to make Greek industry competitive in world markets. This solution has been rejected by Troika, of course, although we now know that the IMF wants ‘debt relief’ at the expense of the Euro group (ie Eurozone taxpayers).

The trouble with this solution is that it assumes Greek capital can revive with a lower currency rate and that more public spending will increase ‘demand’ without further lowering profitability. But the profitability of capital is key to recovery under a capitalist economy. Moreover, while Greek exporters may benefit from a devalued currency, many Greek companies that earn money at home in drachma will still be faced with paying debts in euros. Many will be bankrupted. Already over 40% of Greek banks loans to industry are not being serviced. Rapidly rising inflation that will follow devaluation would only raise profitability precisely because it will eat into the real incomes of the majority as wages failed to match inflation. There would also be the loss of EU social funding and other subsidies if Greece is also ejected from the EU and its funding institutions.

Eventually, perhaps in five or ten years, if there is not another global slump, either the first or second solution can restore the profitability of Greek capital somewhat, on the back of a Eurozone economic recovery. But it will be mainly at the expense of Greek labour, its rights and living standards and a whole generation of Greeks will have lost their well-being (and their country as they go elsewhere in the world to make a living). Both these solutions mean that Greek labour will still be poorer on average in 2022 than it was in 2008.

The third option is a socialist one. This recognises that Greek capitalism cannot recover to restore living standards for the majority, whether inside the euro in a Troika programme or outside with its own currency and no Eurozone support. The socialist solution is to replace Greek capitalism with a planned economy where the Greek banks and major companies are publicly owned and controlled and the drive for profit is replaced with the drive for efficiency, investment and growth.

The Greek economy is small but it is not without an educated people and many skills and some resources beyond tourism. Using its human capital in a planned and innovative way, it can grow. But being small, it will need like all small economies, the help and cooperation of the rest of Europe.

The no vote at least tells the rest of European labour that the Greeks will resist the demands of European capital. That could encourage others in Europe to throw out governments in Spain, Italy and Portugal that continue to impose austerity at the dictate of the Troika. That, in turn, could bring to a head the future of the Eurozone as a Franco-German project for capital.

No comments:

Post a Comment