In my last post on Greece

(https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/06/06/ten-minutes-past-midnight/),

I said it was ten minutes past midnight for the Greek government and the Eurogroup credit institutions in getting an agreement to release outstanding funds so that the Greeks can meet their obligations to repay the IMF and the ECB loans over the next few months. Remember all these tortuous negotiations are not about ‘bailing out’ the Greek people but simply to avoid the Greeks defaulting on their government debts to the ‘Troika’ (the EU, the ECB and the IMF). None of this money will go to improve or maintain real incomes, public services and pensions for Greeks.

As I write , with less than two weeks to go before the Greeks must make another payment to the IMF, there is a total impasse, with each side waiting for the other to blink and concede. And nobody’s blinking.

Alexis Tsipras, the Greek prime minister, has now vowed not to give in to demands made by the Troika, accusing them of “pillaging” Greece for the past five years and insisting it was now up to them to move. “One can only suspect political motives behind the fact that [bailout negotiators] insist on further pension cuts, despite five years of pillaging,” said Tsipras. “We are carrying our people’s dignity as well as the aspirations of all Europeans. We cannot ignore this responsibility. It is not a matter of ideological stubbornness. It has to do with democracy.” On the other side, the IMF negotiators went home to Washington, implying that no deal was possible with the intransigent Greeks, while the Eurogroup dismissed the latest set of concessions from the Syriza government last weekend within 45 minutes

The reality is that Syriza has already dropped many of its ‘red lines’ supposedly not to be passed since the election of the new government back in January (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/04/28/greece-crossing-the-red-lines/). The 47-page document sent by the Greeks to the Troika last week now includes VAT rises, phasing out of early retirement along with further pension reform, measures to further deregulate the product market, primary surplus targets reaching 3.5% of GDP from 2018 onwards, an increase in the “solidarity tax” on income, the continuation of privatisations and the ‘liberalisation’ of the energy market.

But now it seems that the Syriza leaders will go no further and have balked at two further demands from the Troika; namely further cuts in pensions that would affect many of the poorest Greeks and a 10% rise in VAT on electricity with similar results. That is just too much. After, Syriza has now agreed to austerity measures of more than €2.5bn, more than the previous Conservative government had been negotiating. But extra measures are being demanded because the long negotiations have damaged the economy and government revenues even more.

The Troika has agreed to lower the government surplus target for this year to 1% of GDP, 2% for next year but then head back towards 3.5% by 2018. But even this small ‘concession’ will be too much for the Greek economy to bear. It still means €3bn of austerity measures this year alone and cuts in pensions of up to €900m (0.5% of GDP) this year and €1.8bn (1%t of GDP) next year. Tsipras and Varoufakis would face a massive revolt within the ranks of Syriza if it concedes any further.

The callous disregard of the poverty of Greeks, particularly the old, is shown in the statement of IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard in a blog post (http://blog-imfdirect.imf.org/2015/06/14/greece-a-credible-deal-will-require-difficult-decisions-by-all-sides/). Blanchard blithely pontificates “we believe that even the lower new target cannot be credibly achieved without a comprehensive reform of the value-added tax (VAT) – involving a widening of its base – and a further adjustment of pensions. Why insist on pensions? Pensions and wages account for about 75% of primary spending; the other 25% have already been cut to the bone. Pension expenditures account for over 16% of GDP, and transfers from the budget to the pension system are close to 10% of GDP. We believe a reduction of pension expenditures of 1% of GDP (out of 16%) is needed, and that it can be done while protecting the poorest pensioners”.

But Blanchard’s demand will not protect the ‘poorest’ pensioners as it involves a cut in EKAS, the pension fund for those on lower incomes. A recent poll revealed that 52% of Greek households claimed their main source of income is pensions. This is not because so many people are ‘gaming’ the system and drawing on pensions; it is more because so many Greeks are unemployed without qualifying for benefits or employed but not being paid. If pensions are cut further, a lot of Greek households will really suffer at a time when the economy will likely continue to shrink. 10,000 Greeks have taken their own lives over the past five years of crisis, according to Theodoros Giannaros, a public hospital governor, whose own son committed suicide after losing his job.

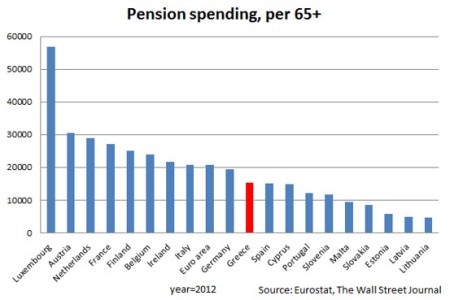

The myth that Greeks are all living off the state and sunning themselves on the beaches with their early retirement pensions – something peddled by the Troika and politicians in norther Europe to their electorates – is just that, a Greek myth. Yes, pensions amount to 16% of GDP, making Greece appear to have the most expensive pension system in Europe. But this is partly because Greek GDP has dropped so much in the last five years. Moreover, Greece’s high spending is largely the result of bad demographics: 20% of Greeks are over age 65, one of the highest percentages in the Eurozone. If you adjust for this by looking at pension spending per person over 65 , then Greek pension outlays are below the Euro average

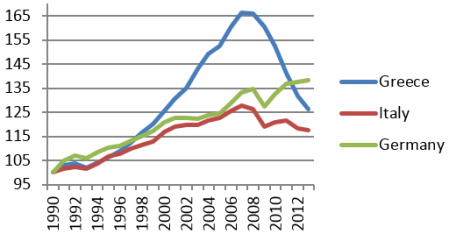

Indeed, the ‘Greek problem’ is not an extravagant public sector employment and pension system, but the failure of Greek capitalism to perform. Greek capitalism expanded before the Great recession, not through productive investment and successful exporting, but through huge foreign borrowing for investing in property and construction (mostly corruptly) led by Greek oligarchs. When the credit bubble burst, Greek capitalism took an almighty plunge leaving the Greek people holding a sick baby. The Greek GDP took off in the second half of the 90s. At its peak in 2008, it had grown by 65%, cumulatively. But by 2013, GDP had fallen back to its 2000 level (see http://www.voxeu.org/article/what-went-wrong-greece-and-how-fix-it .

Real GDP, normalised to 100 in 1990

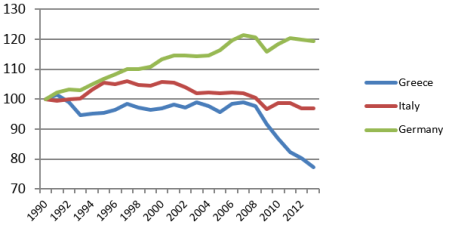

During the ‘euro-boom’ years, the growth rate averaged 4.1% per year and it was mostly explained by (non-ICT) investment. The equally dramatic fall since 2008, -4.4% per year on average, was largely due to labour shedding. Greek workers paid for the failure of Greek capitalism with their jobs and incomes. Because corrupt and feeble Greek capitalism just engaged in property and speculation, relative to Germany, between 1990 and 2008 Greece accumulated a 23% ‘productivity gap’ that persisted and increased in the bust period. The consequence was a huge ‘competitiveness gap’ for the Greek economy. Between 1990 and 2009 the Greek economy experienced a 35% loss in competitiveness, meaning that wage costs (and prices) rose much more rapidly than in its trading partners in the run-up to the crisis.

Total factor productivity, normalised to 100 in 1990

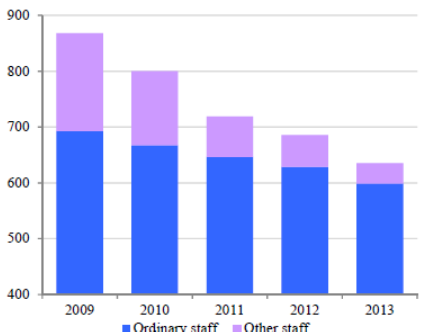

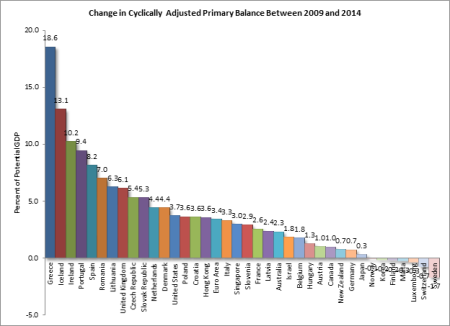

The public sector had to ‘bail out’ the failing banks and the collapsing economy by borrowing hugely. It could only do so by borrowing from the IMF and the EU governments. But then it was in the grip of the devil. The Troika demands huge cuts in public spending so that their loans could be repaid. The level of austerity imposed was about 9 percentage points of GDP – unprecedented in the amount and and intensity (over just three years). Since 2009, government revenues have risen from 37% to 45% of GDP while public expenditures fell from above 50% to 45%.

Greek public employees (‘000).

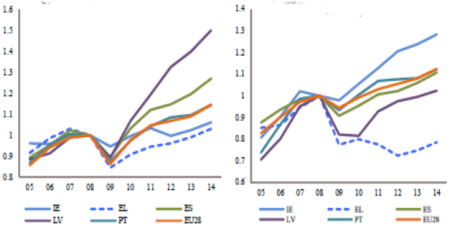

But the huge cuts in wages and employment were still not enough to turn Greek capitalism round. Exports of goods and, in particular, services (tourism), rose by much less compared to other European countries which went through more successful ‘stabilisations’ (Ireland, Spain, Latvia, Portugal). Following the bust in 2009 wages crashed, but prices did not. In a few years, most of the gains in real wages obtained since 1990 were gone. Poverty and inequality rocketed. So Greek labour has paid to re-establish the profitability of Greek capital – but to no avail.

The problem is that Greek capitalism is just too feeble to recover on its own. Most Greek firms are very small (well below 10 employees) and their size makes them unable to access foreign markets. This lends the lie to those in Syriza who argue that help to small businesses is the way out for Greek capitalism. What is really needed is the development of high productivity, innovatory sectors – and that will only be possible through the state. Greek exports are concentrated in low and medium-tech goods, such as fuels, metals, food products and chemicals. According to the Atlas of Economic Complexity, developed at Harvard University, the 2008 gap between Greece’s income and the knowledge content of its exports was the largest in a sample of 128 countries. By 2013, Greece ranked 48th in the Atlas’s index of complexity of exports – by far the lowest of any developed country in Europe.

The Troika has spent its time trying to squeeze labour even more through ‘labour market reforms’ (freezing minimum wages, ending collective bargaining, having part-time contracts, easy dismissals etc) when the the reforms that are really needed are with Greek companies themselves. What should be done is to break the corrupt grip of the oligarchs in the major corporate sectors who monopolise the economy and control investment and prices. This concentration of power in the hands of a few has blocked innovation and growth. In Greece, the power of these ‘insiders’, the oligarchs, have stopped proper tax collection or investment.

The terrible irony is that more fiscal austerity measures will only result in a deeper depression and an even higher public debt ratio (probably going above 200% of GDP). Syriza accepted the 1% primary surplus target for this year. That is likely to require fiscal measures three times as large to reduce the debt ratio, as the economy could be 5% smaller as a result of the austerity measures and the debt to GDP ratio would jump 9% pts! That’s why the IMF may want more austerity but recognises that it will only work if it is accompanied by the writing off of some of the existing debt (as long as they get paid first!).

As Blanchard put it: “the European creditors would have to agree to significant additional financing, and to debt relief sufficient to maintain debt sustainability. We believe that, under the existing proposal, debt relief can be achieved through a long rescheduling of debt payments at low interest rates. Any further decrease in the primary surplus target, now or later, would probably require, however, haircuts.” But the Eurogroup won’t countenance that, as it would be ‘letting the Greeks off’ when others like Ireland or Portugal got no such help.

What is clear now is that if no agreement is found by 30 June, Greece will default on its IMF repayments. This has already been announced by some Syriza ministers. It would be followed by a default on ECB repayments in July. The negotiations over existing ‘bailout’ package would be over as the four-month extension would pass. With default, even if only ‘technical’ as the IMF would allow ‘30 days grace’ to pay, the ECB would consider the Greek banks insolvent and so end its emergency liquidity assistance. With deposits disappearing out of the banks, the government would have to introduce capital controls to stop the flow. Within a few weeks, the government would not be able to pay its workers their wages or meet the pensions outgoings. That would force the government to introduce a ‘parallel’ currency, namely IOUs to pay, which would soon be worth less than a euro by some margin. The impossible triangle will prove impossible: Greece in the euro; a reversal of austerity and Syriza united in government. One or more of these corners will fold.

The Left inside Syriza consider this the opportunity to take over the banks, reverse the privatisations agreed to and to exit the euro forthwith. It may well be. But 80% of Greeks want to stay in the euro and they will need a lot of persuading that Grexit is the right way forward. If Grexit just means a currency devaluation without moves to end the control of the economy by the oligarchs and foreign multinationals, then it can only mean bankruptcy for many small businesses, huge inflation and deeper depression for some time.

The path of default and devaluation by Iceland did not end austerity. On the contrary (and against the impression given by Keynesian Paul Krugman), Iceland is second only to Greece in the world in the size of its fiscal austerity measures since 2009. In Iceland, real primary expenditures fell by 12.7% between 2009 and 2012 by slashing current expenditures, transfers, maintenance and investment, and by freezing public sector wages and benefits for a period of four years, during a time when inflation soared due to the 50% depreciation of the króna. VAT was raised to 25.5%, which at that time was the highest in the world!

Would Greece outside the euro recover eventually? It depends on what happens to the economy inside Greece: does it stay in the hands of Greek capitalists or can labour take over; and also it depends on whether the rest of European labour can mount a successful campaign for a pan-Europe plan for growth. Under capitalism, the dark cloud of a new recession is on the horizon. If that materialises, the very existence of the Eurozone is threatened.

No comments:

Post a Comment