Rising inequality of wealth and income and the risk of stagnation in modern economies occupied the minds of the gurus of mainstream macroeconomics at the annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA)/American Economics Association (AEA) – https://www.aeaweb.org/Annual_Meeting/.

The AEA/ASSA 2015 in Boston was attended by over 12,000 people and upwards of 2000 economists gave presentations. The sessions were kicked off by the star of the inequality debate, French economist, Thomas Piketty, the author of the 700 page book, Capital in the 21st century, the huge best seller of 2014 and winner of the FT’s business book of the year. He was accompanied by an array of Nobel prize-winning economists offering their angle on Piketty’s book and the impact of evidently rising inequality in wealth and incomes in the major capitalist economies over the last 30 years.

I have discussed Piketty’s work in several posts before (see my new book, Essays on inequality, https://www.createspace.com/5078983) and I was also in Boston to present a paper on Piketty’s book (see below, Piketty and the search for r). What was interesting about the Piketty session was the attack launched on him by Greg Mankiw and other neoclassical economists. Mankiw is a leading economist at Harvard University, and author of the main textbook on economics used by students. He has battled against the evidence and implications of the work of Piketty and others that show the sharp rise in inequality during the so-called period of neoliberalism since the 1970s. Indeed, Mankiw has already argued before that inequality is really a good thing, as the top 1% deserve their wealth and do good things for the economy (see my post,

http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/06/19/defending-the-indefensible/).

He and his supporters on the panel now suggested that rising inequality was not bad and/or it did not matter anyway for a properly functioning economy and society. Piketty defended his data and his view well that rising inequality threatened to cause social instability if it continued (as he expected) and action was needed

(AboutCapitalInThe21stCentury_preview).

But it does seem that the euphoria over Piketty’s book from even its original supporters like Paul Krugman or Joseph Stiglitz is waning. Before ASSA, Krugman spoke at a Columbia Law School Panel discussion with Stiglitz and Branco Mankovic in which he argued that “Piketty put inequality on the map but we have got carried way by the comprehensive nature of his explanation”. And at ASSA, Stiglitz started to develop arguments that Piketty’s categories for wealth and capital were faulty and did not prove his predictions (see Milanovic and Stiglitz on capital versus wealth).

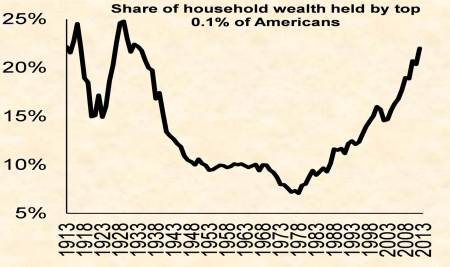

As I have argued before, the problem with Piketty’s analysis is not really the data – the evidence is strong for the rise in inequality. The latest Global Wealth report published by Credit Suisse confirms the Piketty/Saez/Zucman data of the U-shaped curve in inequality of wealth and income in the 20th century – falling inequality from the late 1920s to the 1970s and then a sharp rise back to the levels of the late 1920s (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/10/15/global-wealth-1-own-48-10-own-87-and-bottom-50-own-less-than-1/.)

Professor Shorrocks and the other economists reporting for Credit Suisse found that the share of the top 1% of the world’s income holders peaked at 20% in 1928, eased below 10% by the 1950s , bottomed at 8% in 1970s and then rose sharply after 1980 and returned to peak of 1920s. The inequality of wealth is even worse with the top 1% holding 48% of the world’s personal wealth. In effect, there is a ‘power law’ distribution globally for income and wealth.

The real problem is that Piketty’s explanation for rising inequality is faulty and his proposals for action either utopian or ineffective. This is where the heterodox/Marxist view of inequality comes in. While the likes of Piketty and Joseph Stiglitz entertained thousands in the big halls at ASSA, heterodox economists (including me) in the Union of Radical Political Economics presented papers to about 30-40 on Piketty exposing the flaws in his explanation. My paper argued that by deflating productive capital into a wider definition including property and financial wealth, Piketty cannot really explain rising inequality. Indeed, when housing and financial assets are stripped out, Piketty’s rate of return on assets becomes Marx’s rate of profit. And, instead of being steady and invariable as Piketty claimed, it falls.

Two main arguments have been presented by Piketty, both based on mainstream economics, to explain why the ratio of capital (wealth) to income has been rising. Piketty relies on neoclassical marginal productivity theory. This theory suggests that the more capital invested should lead to falling returns but Piketty claims there is a high rate of substitution of labour for capital in production, so the share of income going to capital rises. But as Fred Moseley showed in a paper at ASSA, marginal productivity is logically incoherent and empirically false (Moseley-Piketty).

The other argument from Piketty is that, over the long term, as the savings ratios of households rises, it will eventually lead to a rising capital share. Well, a paper by Frank Thompson at the University of Michigan showed that, while this is theoretically possible, it is extremely unlikely to be achieved (URPE@ASSA Piketty presentation (n 9) and indeed, others calculated that it could take 200 years of balanced economic growth to explain rising capital share and inequality by rising savings rates!

As the URPE sessions showed, a simpler and clearer explanation of rising inequality in the last 30 years in most economies is increased exploitation of labour by capital. There has been a rising rate exploitation along with a huge switch of value into the financial sector which is owned and controlled by the top 1%, or even just the top 0.1%. Marx’s exploitation theory is a better explanation of inequality compared to marginal productivity or rising savings rates. The so-called neoliberal period was characterised by holding down wages, globalisation, a reduction in job security and privatisation of public services, all of which boosted the rate of surplus value. So we entered the world of super-managers, oligarchs and top families that Piketty describes in his book.

But suggesting that rising inequality is the result of increased exploitation of labour by capital is not comfortable for mainstream economics, including Piketty, as it suggests something nasty about the capitalist mode of production, which the likes of Piketty, Stiglitz and others still support.

Anyway, inequality may lose its fashionable status among mainstream economists in 2015. Piketty’s book may have been a best seller in 2014, but it also won the prize for the ‘least read’ book purchased (as measured by the percentage of the book reached in Kindle – apparently most stopped reading at p26 out of 700pp), taking over that mantle from Stephen Hawkins’ Brief History of Time.

The latest economic data released in the first week of January from the major economies suggest that even the US and the UK may have peaked in growth at the end of 2014, while the Eurozone and Japan continue to sink or stagnate. So the key issue in 2015 may well be whether the major economies have entered a period of ‘secular stagnation’ (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/11/30/secular-stagnation-or-permanent-bubbles/). And indeed, this was the issue that occupied the top mainstream economists in other debates at ASSA.

In the second part of my report on ASSA, I’ll deal with this.

No comments:

Post a Comment