Financial markets got very excited this week when Greece’s conservative PM Antonis Samaras announced that he was going to bring forward an upcoming parliamentary vote for a new president to this month from February. Greek stock prices fell nearly 20% in two days, the biggest fall since the global crash of 1987.

Investors are really worried that if Samaras fails to get his candidate elected as President after three voting chances in parliament, a general election will have to follow in January. That could lead to the victory of the leftist opposition party Syriza (Syriza leads by 6-8%pts in the polls). Then Greece would have a government pledged to renegotiate the debt owed to the EU/IMF and to reverse many of the austerity measures imposed by the Troika (the EU Commission, the IMF and the ECB) as conditions for loans of nearly €300bn made to Greece since 2010. That could provoke a new crisis in the Eurozone.

The term of Greece’s incumbent president is nearly up, and while the role is primarily ceremonial, the president still has the power to call elections and ‘arrange’ coalitions. The decision of Samaras to go for a snap presidential election vote in parliament two months early was forced on him.

Samaras and his junior partner in government, Venizelos from Pasok, are between a rock and hard place. They wanted to ‘exit’ the existing troika programme in 2015 without any ‘lines of credit’ being introduced, as Portugal has already done. But that has not proved possible because they still need a final tranche of funds from the Troika to tide them over and the Troika won’t deliver unless 1) the Greek government meets new fiscal plans and targets and 2) Greece takes a line of credit from the IMF to fall back on once the Troika program ends.

But it is political suicide in any 2015 parliamentary election for Samaras to accept more fiscal austerity beyond that agreed and a line of credit that ties him to the IMF, after having told the Greek electorate that austerity is over and the rule of the Troika is done with.

So Samaras has gambled by going for an early presidential vote without any agreement with the Troika, given that the Euro leaders have agreed to a two-month extension on the program without imposing extra austerity. This is a small window of opportunity for Samaras. However, he must win the presidential vote for his candidate or he will be forced into an early general election.

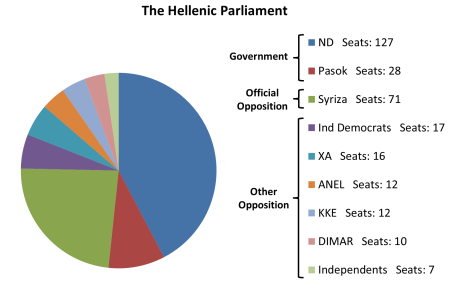

The coalition has a small majority in parliament (155 votes out of 300). But the presidency is only achieved with 180 votes, so he needs a minimum of an extra 25 MP votes. Samaras cannot get this from Syriza, the Communists and the Fascists, so he is left with independents, the Greek Independents and the smaller left parties. Up to now, they have been opposing his policies in parliament so he is up against it in getting the necessary votes.

But he may get them for two reasons: 1) independent MPs may fear they will lose their seats if there is an early general election and 2) they may not want the populist left Syriza party to win an election. So the financial markets may be over-pessimistic because if Samaras can twist enough arms and offer enough bribes he may manage to get the extra votes he needs. There are three votes between 17 December and 29 December and it will probably go to the wire on the last vote.

His candidate is former European Commissioner Stavros Dimas, very acceptable to the Troika and possibly respectable in the eyes of MPs and even parts of the Greek electorate. If he can get Dilma elected, the crisis is over and the government will have another two years in office, with the hope that the Greek economy will recover along with the Eurozone and conditions for the average Greek will improve, giving him a chance to win another election in 2016.

If he manages to get this done, it will be a political blow to Syriza. Samaras’ motivation is to split the opposition, “removing uncertainty and restoring political stability ….. when the current parliament elects a president at the end of the month, the clouds will be gone and the country will be ready to officially enter the post-bailout era.” Samaras decided it was better to go now while he is still ‘resisting’ Troika demands for austerity rather than wait until February when his position would be even weaker.

But it is a gamble. Even if Samaras wins over every independent lawmaker, which is unlikely since some have openly promised to vote against the government candidate, he would still fall short by one vote. Indeed, if all opposition lawmakers vote against the government nominee, that will be enough to bring down the government: the five opposition parties control 121 seats, the exact number needed to prevent a government win.

If Samaras does fall short, then a general election in January would probably means a victory for Syriza in coalition with some smaller left parties. It is unlikely that the Euro leaders will agree to anything that Syriza wants and so a stalemate will ensue that will create huge uncertainty in financial markets and push the Greek economy back into an immediate crisis. Also, a Syriza government may well become a beacon to other populist movements in the periphery that could impel them forward. This is the risk for the Greek ruling class. However, if Samaras can pull it off, he can ‘save’ Greek capitalism from disaster and a takeover by the ‘forces of labour’ as represented by Syriza.

The long-term problems remain, however. After five years of severe austerity and depression, when the living standards of the average Greek household have fallen by 40% and poverty (and starvation) haunt the streets of Athens and the countryside, the government is at last running a surplus on its annual budget (revenue over spending, excluding debt interest). So it does not need to borrow more from the Troika. And the government is forecasting a rise in real GDP in 2015 for the first time since 2009. But really the best that can be said for the economy is that it has finally stopped plunging into an abyss and has hit the bottom – hard. Government debt still stands at 175% of GDP, even after a ‘restructuring’ of the debt owed to European banks back in 2012 (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/03/09/greece-the-biggest-debt-default-in-history/).

There is no prospect of that debt ratio being reduced to 120% by the end of the decade as demanded by the Troika. And even that level is twice what is acceptable to the Euro leaders as the maximum in the decade beginning in 2020. Greece is burdened with a such a heavy level of public (and corporate) debt that Greek taxpayers and small businesses will have to service, that it will keep living standards at ‘third world’ levels for a generation. No wonder Syriza’s demand for a renegotiation of the debt with the EU is so vital.

Unemployment (26%), particularly youth unemployment (50%), remains near record levels with little sign of a significant reduction.

Those Greeks who are well off enough to leave the country have done so to seek work elsewhere and, of course, very rich Greeks have taken their money and capital already to the likes of London to purchase big mansions.

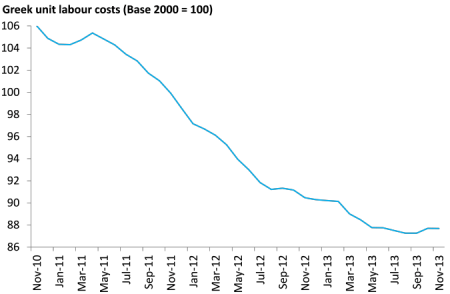

One thing has been achieved by the depression and the austerity: lower labour costs. Labour costs per unit of (falling) production have dropped 30% since 2010 (see https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/02/11/greece-cannot-escape/).

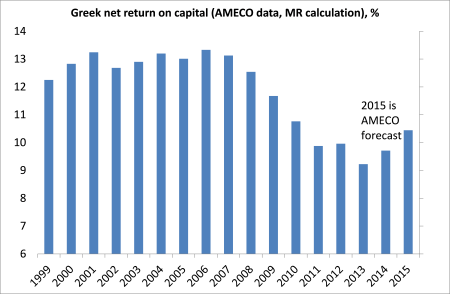

And so the profitability of Greek capital has improved. But even so, profitability is still way below the peak of 2006 before the Great Recession and the Eurozone depression..

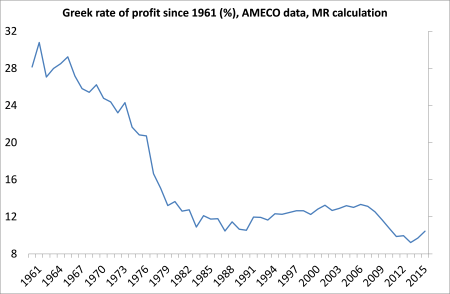

… and has hardly recovered on a long term perspective.

Investment is now lower than it was in the late 1960s! Even if Samaras succeeds in his gamble, Greek capitalism remains at the bottom of a hole.

No comments:

Post a Comment