As the World Bank and the IMF meet for their semi-annual meeting this weekend, in a speech, World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim underlined the importance of “addressing inequality” in the world. Kim told students and faculty at Howard University that a recent Oxfam International report had found the world’s richest 85 people have as much combined wealth as the poorest 3.6 billion. And this compared to around a billion people who still live on $2 a day, have no electricity, drinking water, or even latrines.

The evidence of growing inequality of wealth and income globally is now overwhelming. In a new report, the OECD finds that global income inequality is now back at 1820 levels (http://www.oecd.org/newsroom/how-was-life-shows-long-term-progress-in-key-areas-of-well-being.htm). OECD researchers studied income levels in 25 different countries, charted them back in time to 1820 and then collated them as if the world were a single country. “The enormous increase of income inequality on a global scale is one of the most significant -– and worrying -– features of the development of the world economy in the past 200 years,” concluded the OECD in its 269-page report. Interestingly, the OECD noted that global inequality rose once globalisation took root after the 1980s.

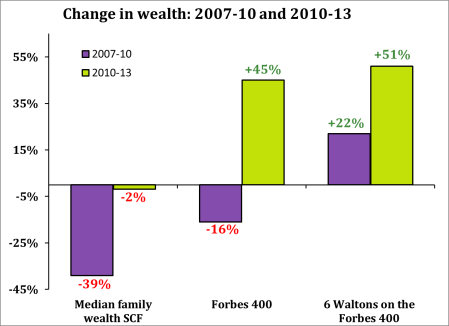

And within the US alone, the latest triennial Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) from the Federal Reserve (http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2014/pdf/scf14.pdf), reveals how the rich have got richer compared to the rest of us, even after the Great Recession. In the Great Recession, net wealth for the average American household fell 39%, but just 16% for the top 400 American families (as measured by Forbes magazine), while net wealth actually rose for the Walton family (who are part of the 85 Oxfam people), the owners of the cut-price, anti-labour American retailer, WalMart (up 45%!). Recession was good for the Waltons.

It was the collapse of home prices that hit the average American household the most, while the fall in stock priced affected the richest 400 more. In the ‘recovery’ since 2010, the average household has experienced a further fall in wealth (-2%), but the top 400 have gained an extra 45%, while the Waltons have added another 50%! Typical US family wealth in 2013 was $81,200 — which is about the same as it was in 1992 at $80,200 (in real terms). The cumulative wealth of the Forbes 400 was about $2.1 trillion, or roughly the same as that held by the entire bottom 60% of American families. The combined worth of the Walton Six was $145 billion in 2013, which equalled the total wealth of the bottom 43%!

The Fed and OECD studies confirm a myriad of others, including the most comprehensive by Anthony Atkinson (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/07/14/the-story-of-inequality/) and, of course, the best-selling book on the rising inequality of wealth in the major economies by French economist Thomas Piketty, “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” (see my posts, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/04/15/thomas-piketty-and-the-search-for-r/).

FT columnist Martin Wolf in his latest book (The shifts and the shocks) also launches the idea that inequality is the main problem of capitalism. “It is increasingly recognised that, beyond a certain point, inequality will be a source of significant economic ills.” Wolf cites the Federal Reserve study above on inequality of income where the top 3% income earners got 30.5% of total incomes in 2013. The next 7% received just 16.8% and this left barely over half of total incomes to the remaining 90%. The upper 3% was also the only group to have enjoyed a rising share in incomes since the early 1990s. So inequality keeps rising.

Wolf also cites the Morgan Stanley study which lists among causes of the rise in inequality: the growing proportion of poorly paid and insecure low-paid jobs; the rising wage premium for educated people; and the fact that tax and spending policies are less redistributive than they used to be a few decades ago. According to the OECD, the US ranked highest among the high-income countries in the share of relatively low-paying jobs. Moreover, the bottom quintile of the income distribution received only 36% of federal transfer payments in 2010, down from 54% in 1979. The poorest are getting a smaller share of available welfare benefits.

Wolf then trots out the argument still dominant among leftist and Keynesian economists that rising inequality is not only unjust but that it is the principal cause of crises and stagnation under capitalism. The argument goes: “up to the time of the crisis, many of those who were not enjoying rising real incomes borrowed instead. Rising house prices made this possible. By late 2007, debt peaked at 135 per cent of disposable incomes. Then came the crash. Left with huge debts and unable to borrow more, people on low incomes have been forced to spend less. Withdrawal of mortgage equity, financed by borrowing, has collapsed. The result has been an exceptionally weak recovery of consumption.”

The argument that the Great Recession and the weak recovery were due to a collapse in consumption just does not hold up – see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/03/11/is-inequality-the-cause-of-capitalist-crises/.) But Wolf’s propositions are now the conventional wisdom of the left or liberal wing of mainstream economics.

I have argued before that there are two reasons for this. First, the powers that be (IMF, OECD, World Bank etc) are genuinely worried that growing inequality could lead to a political and social backlash by the poor against the rich that could threaten the capitalist system itself. Second, claiming that growing inequality is the real cause of slumps in capitalist production is a comforting theory because it suggests that, with a judicious policy of redistribution of wealth and incomes, crises could be eliminated without the need to replace the capitalist mode of production. So nobody on the left (let alone the mainstream) pays any attention to the causal explanation of crises provided by Marxist economics.

Inequality may be seen as the issue by the liberal left and Keynesians, but it is certainly not by the hardline neoclassical mainstream. John Cochrane is a leading University of Chicago neoclassical economist (http://johnhcochrane.blogspot.co.uk/). He is a strong critic of all this liberal ‘fuss’ about inequality. At a recent panel on inequality organised by the Hoover Institution in memory of another neoclassical great, Gary Becker, Cochrane commented that asking for the redistribution of wealth and income was pointless because “we all know there isn’t enough money, especially to address real global poverty” and yet the ‘liberals’ keep insisting on trying to. “I think it is a mistake to accept the premise that inequality, per se, is a “problem” needing to be solved and to craft alternative solutions. Inequality is a symptom of other problems.”

Cochrane starts with the argument that the top wealth owners, like the Waltons or the Steve Jobs at Apple, have ‘earned’ their wealth. It’s the same view expressed by Greg Mankiw, the doyen of economics textbooks, in his (indefensible) defence of the top 1% (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/06/19/defending-the-indefensible/). You see, some people are more skilled than others or luckier than others and so get better-off. It is nothing to do with ‘cronyism’, or ‘rent-seeking’ i.e. the ownership of capital. The answer to inequality is thus more education for the unskilled, not more taxation of the rich.

But be careful, says Cochrane, state funded education would be a bad idea as people will train up as art historians or such rather than in skills useful for jobs in the capitalist economy and we cannot have that. And education must be directed to those where it will work. At the lower end, we just have single mothers, criminals, druggies and other ‘low lifes’ and no amount of education or redistribution of income in benefits etc will change them. After all, “70% of male black high school dropouts will end up in prison, hence essentially unemployable and poor marriage prospects. Less than half are even looking for legal work.” Thus Cochrane drags up the old argument that ‘incentives’ (money, status etc) really only works for those who are already rich to make them do productive things, while ‘incentives’ like benefits or free education and health etc are useless for the poor.

Anyway, Cochrane goes on “as rich people mostly give away or reinvest their wealth. It’s hard to see just how this is a problem”. So that’s all right then. But it is also not true. There are many studies that show poorer people give more to charities as a percentage of their income that the richest. And most of the giving by the rich ‘philanthropists’ is for tax avoiding purposes and the kudos of supporting ‘the arts’ or universities like Cochrane’s Chicago. The Waltons are noted for their lack of philanthropy.

Cochrane then comes up with the well-versed argument that actually global inequality has been declining, not rising. This proposition is based on looking at inequality between nations not within nations, as the OECD or Fed studies above do. Branco Mankovic, formerly of the World Bank, has done the work and shown that the gap between an average household in the emerging economies and those in the rich countries has narrowed over the last few decades (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/10/27/workers-of-the-world-cannot-unite-conclusive-evidence/).

But this is only for one reason: China. The huge growth in the Chinese economy and the rise in living standards there explain nearly all of this improvement – strip that out and it is the same old story – no change. Cochrane has to admit that China is the reason but argues that China succeeded by not taxing its rich people but by growing. Yes, fast growth is the factor, but it is also the case China’s inequality ratios have rocketed so that inequality of income there now matches the levels in the US.

Nevertheless, Cochrane tells us that Bill Gates being a super-rich billionaire is hardly a problem for the body politic of human civilisation compared to murderous dictators who killed millions like Mao Tse-Tung or Joseph Stalin. Poor people don’t worry about rich people getting richer as long as their own living improves “just what problem does top 1% inequality really represent to them?” Well, as the global financial crash has exposed, it is the greed of the bankers, hedge fund speculators making their billions that eventually caused the huge loss in wealth for the average American recorded by the Fed above. So just letting the rich do what they want with our money is a problem.

And as for the poor revolting against capitalism because of rising inequality, don’t worry, “Maybe the poor should rise up and overthrow the rich, but they never have. Inequality was pretty bad on Thomas Jefferson’s farm. But he started a revolution, not his slaves.” Perhaps Cochrane ought to be more cautious: the poor have not always docilely accepted the extravagances of the rich. History is the history of class struggle as just three examples show: the Peasants Revolt of 1381 in England; the French revolution of the late 18th century and the Russian revolution of the early 20th century. Indeed, if the Waltons and the super rich have nothing to fear from the rest of us, why do they spend so much effort stopping trade unions, using police and other forces to crush any protests and intervening around the world against regimes and people who appear to object to their rule? The rich appear more worried than Cochrane.

Finally, we get the Hayek argument to defend inequality. Just after 1945, Friedrich Hayek, a right-wing market economist and main protagonist in opposition to Keynesian views, argued that more regulation and redistribution would put everybody on the ‘road to serfdom under an all-powerful state, Orwellian-style. Cochrane says that ‘liberals’ that advocate higher taxes and regulation on the rich would so the same.

The problem with this argument is that Hayek was wrong. Tax rates on the top 1% reached 90% under Eisenhower in the 1950s but the economy kept on growing fast by historic standards and dictatorship medieval style did not appear. The golden age of the US economy was in the 1960s when economic growth was 4%-plus a year, inequality declined (according to Piketty) and living standards of the poor rose sharply. Growth was much lower when corporate taxation and income tax for the rich was cut in the 1980s onwards, inequality grew and living standards stagnated.

So let’s sum up. The ‘liberal’ Keynesian wing of mainstream economics is pushing the argument that rising inequality of wealth and income is the issue for capitalism and the globe. It is generating social instability and is the main cause of crises under capitalism. The neoclassical right-wing of mainstream economics dismisses this as rubbish. Inequality is part of capitalism, sure, but is not a social or economic problem and indeed any attempt to correct the market forces at work that have created will make things worse by helping state-run dictatorships to develop. It’s the road to serfdom.

In my view, both sides are right and wrong. Yes, inequality appears to be getting worse as a result of the neoliberal counterrevolution and it is not a product of better skilled or educated workers ‘earning’ more, but because those who own or control capital have been taking more. But inequality is not the cause of crises but a consequence of them as the latest evidence of the Fed shows. Yes, redistributing wealth and income through heavier taxation etc may make things worse for capitalism as Cochrane suggests, but only because it would lower profitability at a time when it is near its historic post-war lows. It would not if profitability was high and rising as it was in the 1950s and 1960s.

The idea that inequality is a fact of life that cannot be changed is just apologia for the rich. Serfdom would not follow from the ending of the capitalist mode of production and the expropriation of the super-rich and their capital. We are already serfs compared to the Waltons. With ownership in common, we could plan for need not profit – the best ‘incentive’ of all.

No comments:

Post a Comment