Why the president can't look at Russia rationally

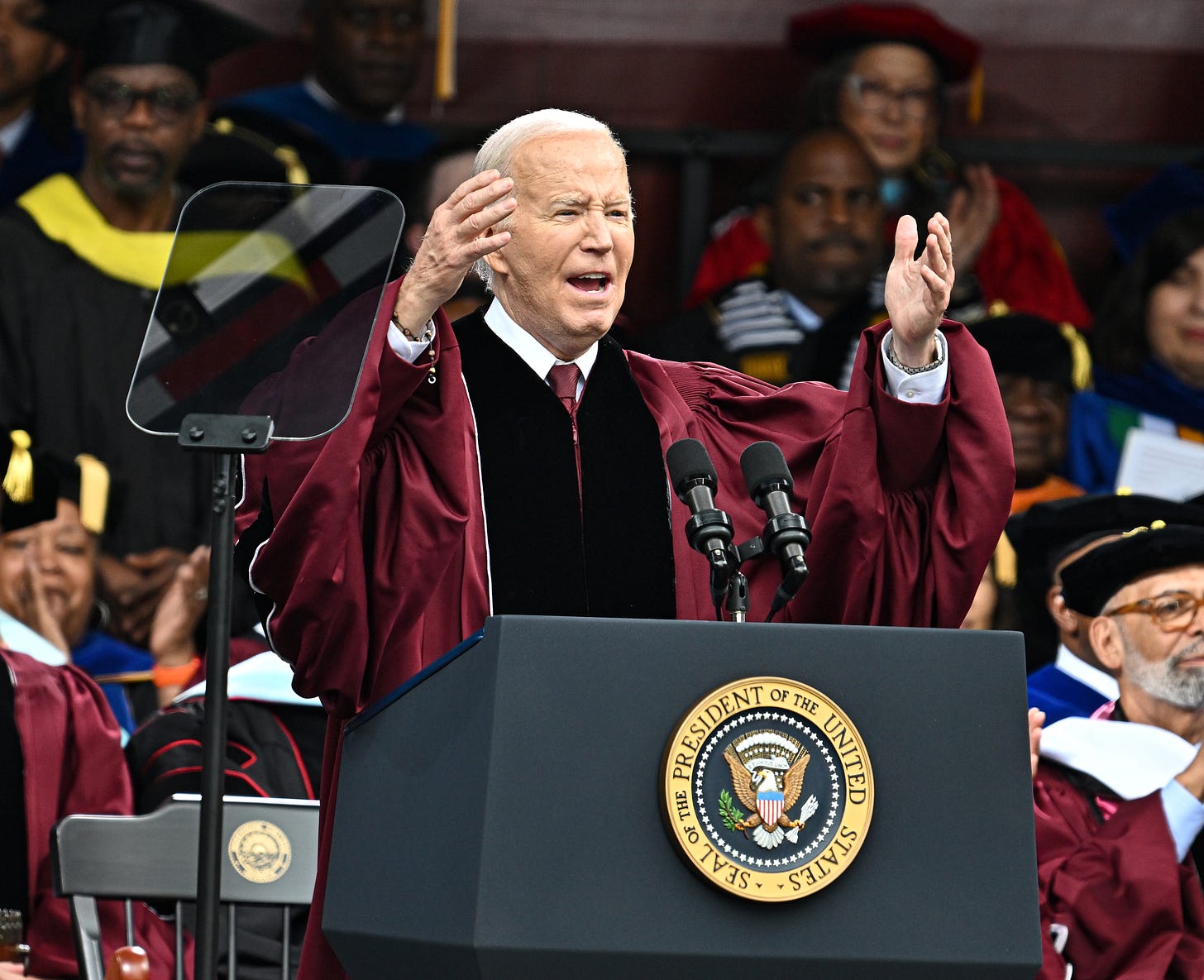

President Joe Biden’s advanced age and the difficulties he has getting through a speech aren’t the only things putting his re-election as risk: another liability is his long-standing inability to see the world as it is. He has made no effort since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022 to arrange a one-on-one meeting with Vladimir Putin, Russia’s President. (Biden and Putin met briefly in June 2021 in what was described as a summit meeting in Geneva. Biden also met with Putin in Moscow while serving as vice president under Obama.)

The president’s disconnect was on display in March in what current polling suggests may have been his final State of the Union address. In the president’s telling, the ongoing war between Putin’s Russia and Volodymyr Zelensky’s Ukraine had turned into an existential crisis in which the future of America was at stake.

“[M]y purpose tonight,” the president said, “is to both wake up the Congress, and alert the American people that this is no ordinary moment. . . . Not since President Lincoln and the Civil War have freedom and democracy been under attack at home”—a reference to the then pending presidential re-election campaign of Donald Trump—“and overseas, at the very same time. Overseas, Putin of Russia is on the march, invading Ukraine and sowing chaos throughout Europe and beyond. If anybody in this room thinks Putin will stop at Ukraine, I assure you, he will not.”

It is easy for an American to dislike Putin, who puts reporters in jail and tolerates no significant political opposition, including the assassination of his enemies. I have turned down requests in recent years to travel to Moscow for political meetings for those reasons. But there are those in the American intelligence community who believe that America bears its own responsibility for the war in Ukraine. Putin and his predecessors in Moscow watched for three decades—since the reunification of Germany in 1990—as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) added member states that brought NATO to Russia’s doorstep. Putin’s apparent fear as the Biden administration took office—that Ukraine would be the next to sign up—could have been soothed with a few words from Washington. But none was coming from Biden and his key foreign policy and national security aides, who echoed the president’s dour fears about Putin’s intentions.

As those who follow the news know, this is boilerplate history. But there have all along been concerns among some inside the American intelligence community about what are seen as Biden’s irrational views on Russia and Putin, dating back to his days in the Senate.

One longtime senior American official stunned me recently, saying that he has concluded that Biden sees Putin as a “Death Angel”—someone, the official explained, “who will try to trick you into believing he is a good person.”

Biden is joined in his hardline stance toward Russia by his two senior foreign policy aides— Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, both of whom are masters of making self-serving leaks to friendly journalists. Having failed a recent series of negotiations with Israel and Hamas to obtain a ceasefire and hostage releases in Gaza, Blinken returned last week from a visit to Ukraine with a recommendation—one that quickly was made public—that the White House should relax its current ban and, as the New York Times reported, expand the losing war by permitting the Ukraine military to target missile and artillery sites inside Russia. The Times noted that the president and his aides believe that there is a red line that, if crossed, would unleash a strong reaction from Putin, although they do not know where or what that red line may be nor do they know “what the reaction might be.”

Such is the haphazard state of the Biden administration’s foreign policy.

In his State of the Union speech, Biden repeatedly strained credulity in his urging of Congress for more funding for Ukraine’s war against Russia. He ignored the history of the allied World War II partnership by describing NATO as “the strongest military alliance the world has ever known.” He added:

“We must stand up to Putin. Send me the Bipartisan National Security Bill. History is watching. If the United States walks away now, it will put Ukraine at risk. Europe at risk. The free world at risk, emboldening others who wish to do us harm.

“We will not walk away. We will not bow down. I will not bow down. History is watching.”

Today, after more than two deadly years of war in Ukraine and little success, the president’s speech sounds stunningly histrionic.

America, in the years Biden has been in office, has spent $175 billion to fight a war that cannot and will not be won. It will only be resolved by diplomacy—if rationality prevails in Kiev and Washington—or else by the overwhelming defeat of the understaffed, undertrained, and poorly equipped Ukrainian army. In recent weeks, I have been told, several Ukrainian combat brigades have not defected, or considered doing so, but have made it known to their superiors that they will no longer participate in what would be a suicidal offensive against a better trained and better equipped Russian force.

The senior adviser, who has followed the war closely, told me: “Putin is playing the long game. He’s secured Crimea and the four Ukrainian provinces”—Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia—after some intense fighting—that he annexed shortly after initiating the war two years ago. “Kharkiv”—Ukraine’s second largest city thirty kilometers south of the Russian border that is a cultural and transportation center—“is his next prize. He’s moving now for a checkmate on the city.”

The all-out assault on Kharkiv, whose citizens are already fleeing, will come at a time of Putin’s choosing, the adviser said. “He’s now fighting for a negotiating position of strength in dealing with Trump, who he thinks is going to win” in November. “He will be in a position of strength—the catbird seat.”

Zelensky, meanwhile, whose five year term as president expired this week—he remains in office under martial law—has been campaigning in newspaper and television interviews

for more American missiles capable of striking targets deep inside Russia, for F-16 fighter jets, for more anti-aircraft missiles, and for troop support from NATO that is unlikely to come.

In an interview with the New York Times

this week, Zelensky spoke of his children and his exhaustion. If he

spoke with gratitude of the $61 billion aid package approved by Congress

last month, the newspaper did not report it.

No comments:

Post a Comment