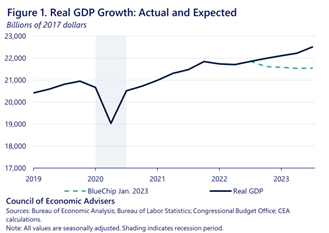

I have been considering why in 2023 the US economy grew by 2.5% in gross domestic product (GDP) in real terms (ie after the official inflation rate is deducted). This growth rate was not forecast by the consensus at the beginning of 2023 – indeed the majority forecast that a slump i.e. a contraction in national output, was more likely – including me.

First, let’s remind ourselves that real GDP may have risen by 2.5%, but real domestic income (GDI) rose only 1.5%. GDP has been growing faster than GDI because there is more consumer borrowing (and running down of savings) and because there is more production without sales. So the GDI measure may well be more accurate about what is happening to the US economy than GDP. But we don’t have the final figure for GDI in 2023 yet, so let’s accept the GDP figure for now.

What happened to deliver this significant, if modest rise in real GDP? The mainstream economists and media go on about how consumption remained strong i.e. American households continued to spend more and it was this that delivered the faster growth than expected. But there are two things wrong with this explanation. First, in 2023 consumption growth was actually slower than in 2022, slowing from a 2.5% rise in 2022 to a 2.2% rise in 2023. Yet real GDP growth accelerated from 1.9% in 2022 to 2.5% in 2023. So this cannot be the main reason for the rise last year.

Second, theoretically, consumption is never the swing factor in economic growth, contrary to the views of ‘simplistic’ Keynesians. In all US economic recessions since 1945, it has been a contraction in investment that has led to a slump and vice versa. Investment leads consumption and is the swing factor.

Yes, consumption growth contributed 60% of the 2.5% real GDP rise in 2023, but that contribution was down from over 90% in 2022 and 2021. Also, the increase in household consumption was mainly confined to spending on healthcare and on leisure services. Most Americans were forced to increase spending on private health insurance and utilities. But spending on other basic items was up only a little. Indeed, inventories i.e. stocks of goods that could not be sold, did not fall in 2023, after a large rise in 2022. So companies still had a hangover of stock in 2023 from 2022.

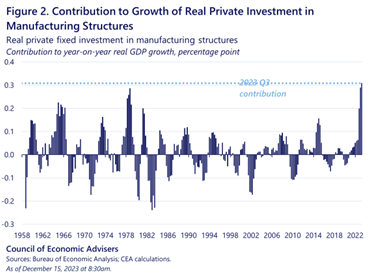

It was business investment that saw the biggest swing to boost real GDP growth. The housing market continued to fall as mortgage rates rose, but investment in new structures and transport (factories, offices, roads etc) rose nearly 13% in 2023, having fallen in 2022. This contributed 0.5% pts (or 20%) of the 2.5% growth. It was in structures that increased business investment concentrated, because investment in equipment (computers,etc) did not rise at all.

What was going on here? Government spending on consumption and investment rose considerably. Under GDP definitions, such spending is regarded as an addition to national output. Having declined 0.9% in 2022, spending rose 4% in in 2023 or a 4.9% pt swing from 2022. Spending both on defence and civil projects rose significantly.

It was the huge tax incentives and subsidies offered by the Federal government and distributed through the states to companies willing to build new plant and factories, particularly in strategic sectors like tech and semiconductors as part of the US administration’s ‘chip war’ against China. It also seems that the biggest spending boost came from the state governments, using unused COVID funds and unexpectedly higher tax revenues. This extra money went mostly on employing government staff in education.

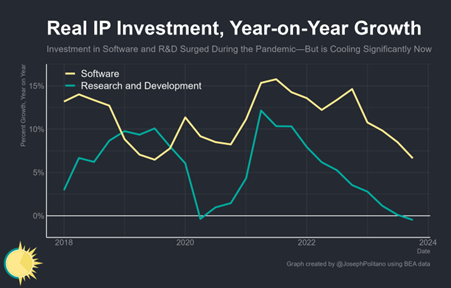

But there were no new tax incentives etc for business investment in equipment etc, so growth in that sector was stagnant. There was a substantial deceleration in the pace of real investments in 'intellectual property' as the tech industry slowed down and higher interest rates weighed on research and development decisions. Over the last year, software investments have grown at the slowest pace since late 2015, while real R&D output outside the software sector has shrunk for the first time since the early pandemic.

Another surprise booster to US economic growth was net trade. Net exports were up 4.4% in 2023 after contracting in the four previous years. Exports were boosted by sales of liquid natural gas and oil to Europe given the loss of Russian energy imports there and by financial services exports, but the main cause of the jump in net trade was a decline in imports as import prices in energy and food fell sharply after two years of sharp rises.

To sum up, the US economy grew modestly instead of going into recession in 2023 because of: stronger business investment funded by government spending; a positive trade balance as energy imports fell; and because of the continuance of a sizeable stock of unsold goods. If all these (mainly one-off) contributions to growth had not happened in 2023, US economic growth (in GDP) would have been just 1.5%, not 2.5%. i.e. lower growth than in 2022.

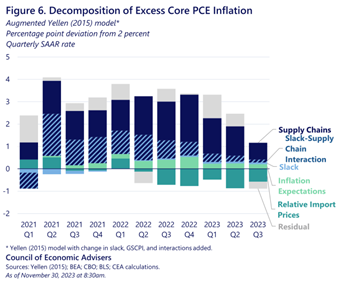

Also, average real incomes rose in 2023 as wage growth outstripped price inflation for the first time since the end of the pandemic. As has been argued in many previous posts, the acceleration in inflation was mainly due to ‘supply-side’ factors: supply chain blockages and stagnant manufacturing output and trade. It’s not been due to ‘excessive demand’ and so the interest rate hikes by the Fed have played little role in halving the inflation rate in 2023. It was the improvement in supply chains that did it.

But the Fed’s rate hikes did not induce a slump in 2023, so does that mean a ‘soft landing’ for the US economy after the ‘sugar rush’ recovery in 2021 has been achieved, or even better, no landing at all but just a strong economic boom ahead?

There are many things to suggest that the factors that delivered faster growth in 2023 will not be around this year. First, investment in manufacturing structures will cool significantly. And the sharply increased spending by state governments is probably a one-off. Also, the decline in software and R&D investment in 2023 is not a good sign for 2024.

Second, net trade is unlikely to contribute to growth in 2024 as import costs will rise again, given a weaker dollar in foreign exchange markets and hits to the global supply chain from disruptions in the Middle East.

Third, the cost of government spending is reaching record levels in debt servicing. Federal government interest payments on bonds have surpassed $1trn and are still rising. Unless the Fed gets interest rates down fast, that is going to eat into the funding of government services (outside defence, of course) as the Biden government aims to reduce spending from hereon.

In 2024, much will depend on whether inflation continues to fall and whether the existing high level of nominal interest rates does not turn into a sharp rise in the real rate of interest (that's after taking inflation into account). If it does, then corporate profits will begin to fall. Corporate profit margins (profit per unit of value added) have flattened out since 2022 and even fell a little in 2023. But they are still very high (if mainly due to high margins for tech and energy companies).

But wage rises are not being compensated for by increased productivity of labour (thus raising the rate of exploitation) and so margins will fall this year.

Corporate profits (that’s margins multiplied by sales) are already slipping towards negative territory.

And it is profits that lead investment that then leads to employment, incomes and consumption – not the other way round, as the Keynesians argue. So slowing or falling profits will reduce the incentive to invest more.

At the same time, the labour market is ‘cooling’. Unemployment is creeping up and the jobs available are mainly low-paid, part-time or temporary. American households are spending more by reducing savings and/or borrowing more (at very high interest rates). No wonder the average American consumer thinks the economy is in a recession, not in a boom. Consumer sentiment improved in 2023, but it’s still way below pre-pandemic levels.

If interest rates stay high and the Fed appears to have no intention of starting to cut rates before the summer, the impact will feed through this year into more corporate bankruptcies (already rising) and perhaps another banking crisis like last March.

And let’s remind ourselves of what was considered to be a very reliable indicator of a recession: the inverted bond yield curve i.e. where short-term interest rates are higher than long-term bond yields. The inversion supposedly shows that investors want to hold ‘safe’ government bonds more than cash or investments, suggesting that they fear a slump ahead. History shows that if the curve remains inverted for long enough, then a recession arrives. The average length of inversion before a recession comes is about 18 months (as with the 1974 and 2008 slumps). The current inversion is about 13 months old.

And looking ahead, the US Conference Board has a leading economic index (LEI) made up of components in the US economy to measure future expansion or recession. This LEI continues to signal recession.

So far, these indicators have not proved right, but we shall see in 2024.

No comments:

Post a Comment