by Michael Roberts

Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington are authors of The Big Con: How the Consulting Industry Weakens our Businesses, Infantilises our Governments and Warps our Economies. They launched their book with big fanfare in London, charging £30 a person to attend the live event.

Mazzucato has built up a big reputation, scanning from the left in the labour movement through to mainstream governments in Europe and Latin America for espousing the benefits of public investment and the public sector over the private. As a result, she has been called “the world’s scariest economist”. Her last book, Mission Impossible, called for public sector-led projects in partnership with the private sector. This could lead to a better management of the capitalist economy (not its replacement).

Now in this new book, Mazzucato and Rosie Collington expose the scam that the management consultancy business is. The premise of Mazzucato and Collington is that consulting is really a confidence trick. “A consultant’s job is to convince anxious customers that they have the answers, whether or not that’s true”. With multiple evidence they show that consultancies have weakened businesses and hollowed out state capacity. “The more governments and businesses outsource,” they write, “the less they know how to do.” As the authors point out, why should “fresh-faced consultants airlifted in from one of the big firms know better than workers on the office floor or staff in the NHS, when they often seem to know very little.” Indeed as management consultant Bruce Henderson once sniggered: “Can you think of anything more improbable than taking the world’s most successful firms and hiring people just fresh out of school and telling them how to run their businesses – and [getting them] to pay millions of pounds for this advice?”

The authors cite, for example, Covid contracts. In the UK, ministers and civil servants relied on consultancies, more than £1m a day with some senior advisers billing more than £6,000 for a single day’s work. And was it successful? We now know that billions were wasted by these consultants, some of whom had no experience at all in healthcare and were just companies that sprang up to take advantage of public money, often owned and run by friends and even relatives of ministers. A parliamentary inquiry into England’s test-and-trace programme, for example, found that “consultants accounted for nearly half of [its] central staff”, and concluded that it had “not achieved its main objective to help break chains of Covid-19 transmission and enable people to return to a more normal way of life”.

One estimate suggests that the UK public sector awarded £2.8bn in consulting contracts in 2022 – up 75% on spending in 2019. Between 2016 and 2019 alone, spending on management consultancies in the NHS more than trebled. One recent academic study on the use of management consultancies in 120 NHS Trusts found that despite “spending around £600m on consultancy over four years, there is no sign of improved efficiency overall”.

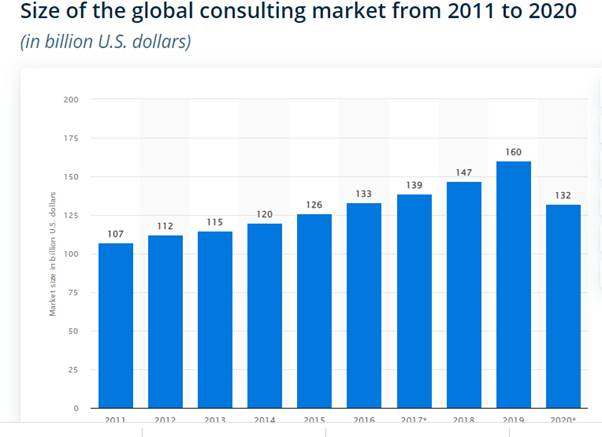

The authors concentrate on the UK. But their story is not new – many others have analysed this parasitic industry and found the same story globally. In 2020, the global consulting market was estimated to be worth approximately 132 billion U.S. dollars.

According to those working within the industry, the leading consulting firm in the United States in 2021 was McKinsey & Company. Other consulting firms in the ranking included the so-called Big Four accountancy and auditing firms – Deloitte, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Ernst & Young (EY), and KPMG, with Deloitte ranking the highest out of the four. Headquartered in New York, Deloitte is a professional services company with several service lines specializing in auditing, tax, consulting, enterprise risk, and financial advisory. In 2022, the firm’s revenue reached approximately $59 billion– over a third of which came from consulting.

The majority of the larger consulting and auditing firms operate on a global scale and have workforces the size of small cities, with offices located in dozens of countries worldwide. In 2022, for example, PwC had almost 120,000 employees in the Asia Pacific region alone.

Across the world, it’s the same scam. As former consultant David Craig explained in his memoir Rip Off!: “We were proud of the way we used to make things up as we went along… It’s like robbing a bank but legal. We could take somebody straight off the street, teach them a few simple tricks in a couple of hours and easily charge them out to our clients for more than £7,000 per week.” It consisted, he says, of “lies, lies and even more lies.”

There are now half a million management consultants in the world and they all claim to be able to enter any organisation, watch its workers for a short period, and then – using graphs, algorithms, and a jargon that makes quantum physics look like Sesame Street – render it dramatically more efficient, for a fee.

And yet studies show this is nonsense. The Cranfield School of Management studied 170 companies who had used management consultants, and it discovered just 36 per cent of them were happy with the outcome – while two thirds judged them to be useless or harmful.

The OECD has studied developed economies over a 20-year period, and it found labour productivity growth was much higher in the countries where it is hardest to fire people. The better you treat a workforce, the better they work. Professor Peter Cappelli studied 122 companies and found that lay-offs most often shrank their future profitability, instead of swelling it.

In Australia, the government spent A$6m (£3.33m) on a contract with McKinsey to help develop its net zero climate strategy, but analysts subsequently found the modelling was full of holes.

There are even criminal outcomes. Management consultancy Bain has been banned from government contracts for three years over its involvement in a South African corruption scandal. The move follows a probe into allegations of widespread corruption during South Africa’s former President Jacob Zuma nine years in power.

The management consultancy con is really a product of neo-liberal ideology that the private sector knows best and will be more efficient than public sector workers doing the job. And it is also a reaction to the falling profitability of the capitalist sector in the 1970s that led to policies of privatization and outsourcing in order to boost profitability. The management consultancy con added little to new value but instead gouged out profits from the public sector and productive capitalist firms. As Michael Heseltine put it one year after Margaret Thatcher took power: “The management ethos must run right through our national life – private and public companies, civil service, nationalised industries, local government, the National Health Service.”

Despite the evidence, the management consultancy business continues to grow. In the UK, ministers have even dropped controls on spending on consultants, removing restrictions that required central authorisation if contracts with groups such as Deloitte, McKinsey and Boston Consulting Group lasted more than nine months or exceeded £600,000.

They are everywhere: in the US, AT&T (to pluck a random company) spent $500m on them in just five years, while the British state will soon be spending more on management consultants than on upgrading its nuclear weapons.

What’s the answer? Mazzucato and Collington reckon “Instead of wasting billions on external consultancies that stand to benefit from the hollowing out of Whitehall, governments should invest internally in creating capable organisations that foster learning and are empowered to take risks.” Whatever that means. The authors do not rule out consultants it seems. “Of course, departments should also work with other organisations and people that can help them achieve their democratic mandates – but this advice should come from the sidelines, provided by people with genuine expertise and experience.” Again, I am not sure what that means.

Surely, the solution comes in ending outsourcing and consultants and instead rely on the workers in firms and governments to improve outcomes. But that would mean giving workers democratic control of production and services and ending the autocracy of grotesquely overpaid chief executives and shareholder power. With workers control of the workplace, integrated into a plan for investment, training and employment, real improvements could be made – with hundreds of billions saved and used more effectively.

No comments:

Post a Comment