On December 6, US president Joe Biden joined Morris Chang, founder of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) in Arizona for a symbolic “tool-in” ceremony to mark the latest step in the chipmaker’s investment in a new factory in the US. TSMC is tripling its previously planned investment at its new Arizona plant to $40 billion, among the largest foreign investments in US history, as President Joe Biden visited and hailed the project.

TSMC is the leading hi-tech chipmaker in the world, with both China and the US importing their products to process their manufactures. TSMC has become the battleground between the US and China in world trade and technology – with the added intensity of Taiwan being the hotspot for geopolitical conflict between the rising economic power of China and the (relative decline) of US dominance globally.

It is in this context that economic historian Chris Miller’s book Chip War has become so relevant. Chris Miller has just won the Financial Times Business Book of the Year Award for Chip War, his historical account of the global battle for semiconductor supremacy. In the book, Miller outlines the development of the semiconductor and how TSMC and a few other manufacturers came to dominate the global supply of advanced microchips. His main message is disturbing. Whereas during the ‘cold war’ between the US and the Soviet Union, nuclear weapons and the potential of mutually assured destruction created some sort of balanced truce that avoided outright conflict, in this ‘cold war’ between the US and China, there is no balance, but instead an unlimited race. “There’s a very clear threshold of nuclear use. [Nuclear weapons] are either used or not used, whereas in the economic interdependence space, there’s no threshold that [shows] you’ve crossed the line. And in fact, there’s lots of different lines one can cross.” (Miller).

Miller argues graphically that microchips are the new oil – the

scarce resource on which the modern world depends. Today, military,

economic, and geopolitical power are built on a foundation of computer

chips. Virtually everything from missiles to microwaves, smartphones to

the stock market runs on chips. Until recently, America designed and

built the fastest chips and maintained its lead to maintain its lead as

the superpower. But now America’s edge is slipping, undermined by

competitors in Taiwan, Korea, Europe, and, above all, China. As Chip War

reveals, China, which spends more money each year importing chips than

it spends importing oil, is pouring billions into a chip-building

initiative to catch up to the US. At stake is America’s military

superiority and economic prosperity.

Miller explains how the

semiconductor came to play a critical role in modern life and how the US

become dominant in chip design and manufacturing and applied this

technology to military systems. America’s victory in the Cold War with

the Soviet Union and its global military dominance stems from its

ability to harness computing power more effectively than any other

power. But here, too, Miller says, China is catching up, with its

chip-building ambitions and military modernisation going hand in hand.

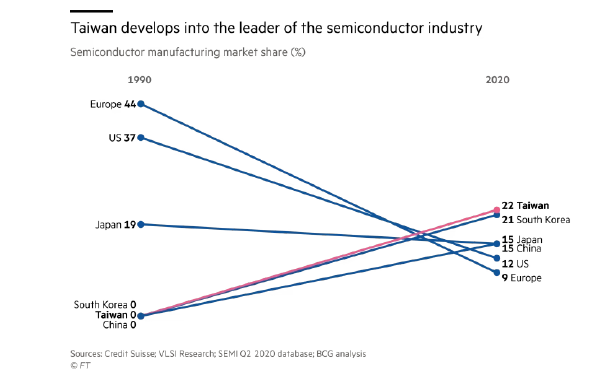

Miller’s history traces chip development from their invention in America, in the 1950s, in the golden era of US capitalism to the establishment of a global supply chain concentrated in East Asia. Today, nearly all advanced processor chips are produced in Taiwan, and Miller mounts a convincing argument that shifting control of the industry could dramatically reshape the world’s economic and political orders. Even more than traditional trade and manufacturing production, and even more than financial might, Miller argues that who leads and dominates in chip production will dominate the global economy.

Chip development and production is now the key area in the US attempt to isolate, weaken and reduce the economic and military power of China and other countries that deem to oppose US global interests. In the past, the US has used the power of the dollar to cut adversaries off from global finance. The new US Chips Act aims to isolate Russia and China from the world’s tech economy and stymie their military capabilities. The Act is part of a wave of US and Western sanctions in retaliation for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Act’s intent was made clear by Kevin Wolf, a former senior commerce department official. “What the administration has done here is set out a structure to cut Russia off from chips and said that this is a policy and a mission,” said Wolf. “And this isn’t going to go away. There is massive allied co-operation on this.”

The Chips Act is just the next stage in a series of measures to weaken China’s tech capabilities and global influence. It started with export control powers on the Chinese telecoms company Huawei during the Trump administration. After first restricting the sale the US technology to Huawei by putting it on its trade blacklist, Washington ratcheted up pressure by applying the so-called foreign direct product rule. This allowed the US to reach beyond borders and control products made outside the country if they are designed or manufactured using American technology. “Huawei was a trial run,” said Christopher Timura, a trade lawyer at Washington’s Gibson Dunn. “The US didn’t see a dramatic impact on Huawei until it developed the entity list foreign direct product rule.”

Using this same power against Russia broadly for some items, and more stringently against a specific list of 49 military entities, means Russia is now effectively denied access to high-end semiconductors and other tech imports critical to its military advancement. “Russia is very well prepared but over time this is going to degrade their military capabilities severely,” said Julia Friedlander, a former US Treasury official.

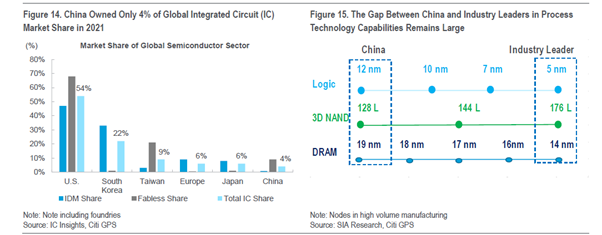

But China is the real target and the battle to crush China’s tech advancement is by no means won. Already, China is the world’s largest consumer of semiconductors. However, its self-sufficiency in manufacturing its own chips is extremely low. Chinese domestic firms had only a 6.6% self-sufficiency ratio in 2021, rising to 16.7% when including foreign firms located in China. Even including these multinational subsidiaries in China, the country’s chip production in 2026 is only likely to reach 6.6% of the global total. In the fabless semiconductor sector, China contributed 16% of the global market in 2020, but its share declined to only 9% in 2021 amid US-escalated export bans.

But Beijing’s policy is one a drive for self-sufficiency in chip production using all the financial and planing powers of the state. In 2014 China established a National IC Development Investment Fund. Later in 2015, the Made in China 2025 plan set an ambitious 70% self-sufficiency target by 2025, which given current progress, is not going to be met. So China’s dependence on the economies that supply it with semiconductors — Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, and Japan especially — will remain, with the risk that supplies will be totally cut off by the US plan.

The main goal of the US CHIPS Act is to fund $52 billion in manufacturing grants and research investment and to provide a 25% investment tax credit to chip producers in the US. But any entity that utilises CHIPS Act funding is prohibited from “engaging in any significant transaction involving the material expansion of semiconductor manufacturing capacity in China”. The US is planning more sanctions: an export ban of semiconductor manufacturing equipment for NAND memory chips with more than 128 layers. The aim is that by blocking China’s biggest NAND company and foreign company-owned memory chip fabs in mainland China, foreign memory chip makers will have to locate outside China, as TSMC is now doing.

Nevertheless, China-located chip production could increase to 21.2% of China’s demand by 2026 from 16.7% in 2021. Moreover, US chip sanctions hits the production and profits of U.S. companies, with some estimating that it could reduce US global market share 18% and hit 37% of their revenue in the long term.

No wonder US firms seem unwilling to restrict their tech exports to China. Also, TSMC may be investing in new plant in the US but this has neither the scale nor the technological level of TSMC’s newest fabs in Taiwan. “Progress on reducing the dependence on TSMC . . . for the most advanced processes will not be reduced significantly until TSMC, Samsung and Intel all site advanced facilities at scale in the US,” says Paul Triolo, a China and technology expert at Albright Stonebridge Group.

Even then, only part of the supply chain will benefit. The fabs that Intel, TSMC and Samsung are building in the US are all for advanced chips, so they will mostly support the PC, smartphone and server industry. However, automakers, which has seen production disrupted due to chip supply bottlenecks, use less advanced chips that struggle to be viable in the US, where costs are higher.

But this chip war in not only about economics; it is about political power in the 21st century – at least for the leaders of US imperialism. Miller makes that clear in his book and in his other works where he seeks to expose the autocratic and imperialist ambitions of Russia under Putin. The struggle to maintain US supremacy and reduce China’s development (and hopefully bring about ‘regime change’) will be very costly to the US economy, but apparently it is worth the cost at the expense of world trade and output – and even world peace.

The US couches this battle in terms of a fight between ‘Western democracy’ and Chinese (and Russian) ‘autocracy’; of a fight for human rights (as represented by US values) against the repression of minorities and dissidents (in China) and even ‘genocide’ (by Russia) in Ukraine. This takes the propaganda to new heights of hypocrisy. What is really at stake is US global supremacy. And that is more important than expanding trade and technology for the benefit of all.

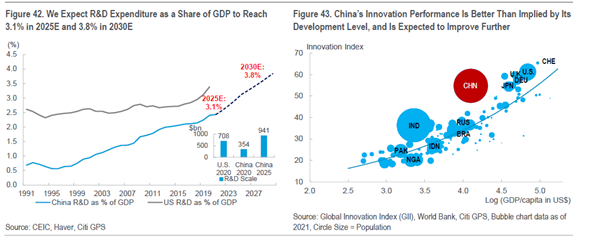

US strategists fear that China can still overcome the blocks that the US is putting in its way. That fear is actually based China’s state-led investment planning that right-wing theorists have called ‘brute force economics’ because it does not rely on the ‘free market’. “In the semiconductor industry, for instance, Beijing’s playbook is on full display. It is leveraging massive amounts of state support, targeted intellectual property theft to aid national champions, knowledge transfer from technical experts trained in the United States and allied countries, and preferential treatment for domestic firms to tilt the playing field in its favor.” Liza Tobin, former China director during the Trump and Biden administrations and the CIA.

That view is also summed up by Keynesian Larry Summers’ comment on Miller’s Chip War (my emphasis underlined). “Semi-conductors may be to the twenty-first century what oil was to the twentieth. If so, the history of semi-conductors will be the history of the twenty-first century. This is the best chronicle of that history so far that we have had or are likely to have for a very long time. If you care about technology, or America’s future prosperity, or its continuing security, this is a book you have to read.”

No comments:

Post a Comment