by Michael Roberts

Colombia has a presidential election today (29 May). According to

public opinion polls, in the lead is Gustavo Petro. A former M-19

guerrilla member, Petro took part in peace talks that paved the way for

the M-19 to disarm and form a left-wing political party in 1990. He

later served a term as mayor of Bogota, the country’s capital.

Afro-Colombian feminist and human rights activist Francia Márquez is

his running mate.

Petro is well ahead in the polls for the first round over establishment candidate, former Medillin mayor Federico Gutierezz. If Petro wins and if former president Lula da Silva pulls off a comeback victory in Brazil this October, the seven most populous nations in Latin America — Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Peru, Venezuela and Chile — will all be under left-wing rule.

Petro is certain to lead in the first round but will probably fall short of 50% of the votes and so there will be a run-off against either Gutierrez or independent ‘business’ candidate Rodolfo Hernandez. If the latter makes the second round, the runoff could be close.

The pandemic hit Colombia hard as it did the rest of Latin America, with almost 60,000 deaths and 5 million jobs affected. Colombia recorded its largest recession on record. Since mid-2020, there has been an uneven recovery, with economic activity not expected to return to pre-pandemic levels until the second half of 2022, if then. The pandemic exposed the unending failure of pro-business governments to support average and poor Colombians. Instead of fiscal support, the incumbent regime implemented a regressive tax on public services. Over five million Colombians took to the streets in May 2021 in unprecedented protests that were met with fierce police brutality.

In 2021, 39.3% of Colombians were living in poverty . Around 18.9 million people remain poor, against 17.5 million before the pandemic. The annual inflation rate in Colombia accelerated to 9.2% in April 2022, the highest rate since July 2000. Rising inflation particularly affects Latin America where the budget share of food and energy prices in the consumption basket is about 40%, with the highest levels in Peru, Mexico, Brazil, and Paraguay.

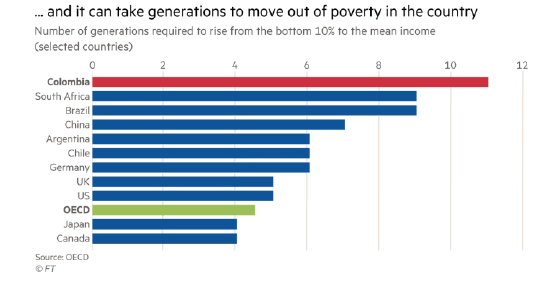

And as in all of Latin America, inequality of wealth and income

is very high in Colombia. The World Inequality Lab estimates that the

top 10% of income earners take 58% of the income generated in Colombia.

Inequality based on wealth concentration is even higher, with the top 10% of wealth holders having 65% of all personal wealth.

The pandemic starkly exposed the divide between the rich and the rest. The Gini index of inequality of income for Colombia is 0.53, placing it as the second-most unequal country in Latin America only after Honduras.

This figure measures the reality of most Colombians struggling to pay for housing, education, transportation. The policies of successive pro-business governments for decades have cemented that inequality. Large portions of public land were sold off to landowners in the 1930s with the expulsion of peasant farmers. So rural poverty remains even higher than in the cities. There is little or no welfare state or benefits to support the poorest. According to the World Bank, malnutrition killed 14 children per 1,000 births in 2018.

At the other end of the spectrum, the rich pay hardly any taxes.

If Petro wins the presidency what does he plan to do? He says he is committed to finding ‘new economic development models’ that do not rely on extractive industries like oil. But he says that expropriations (nationalisations) are off the table and instead envisages a cautious redistribution of Colombia’s wealth. Petro proposes to extend free higher education, guarantee state jobs for the unemployed, end new oil and gas exploration in a country where hydrocarbons make up half of all exports; and increase taxes on the rich to pay for better public health and welfare. He vows to make companies pay 70% of their profits in dividends, bolster state pensions and reform the independent central bank.

He also wants to renegotiate Colombia’s free trade agreement with Washington, arguing that the trade pact has crippled Colombia’s agricultural sector and forced farmers to turn to coca production to make ends meet. “The free trade agreement signed with the United States handed rural Colombia to the drug traffickers,” he says. “Agricultural production cannot be increased if we do not renegotiate the FTA.” He favours legalising the drug trade — although he says this is out of Colombia’s hands and will depend on the consumer nations — and would restore diplomatic ties with Venezuela, where the US does not recognise President Nicolás Maduro and maintains a Venezuela embassy in exile in Bogotá.

These are modest proposals. “Petro has been demonised by the Colombian right, which has been in power for so many years, not just for his militant past but for his systematic exposure of corruption,” says Vanessa Vivero Martínez, an economist from the coffee-growing region of Caldas. “But for me, his proposals are totally liberal and democratic, just like what you would hear in Europe from any social democrat.” Even Petro’s modest proposals can put him in personal danger. Political assassinations have a long history in Colombia. Petro recently had to cancel a campaign trip after information that the La Cordillera crime gang was planning to make an attempt on his life.

But Petro’s reforms do not address the underlying decline in Colombia’s weak capitalist economy. We can gauge this by calculating the rate of profit on Colombian capital. Recently, Carlos Alberto and Duque Garcia studied the connection between economic growth and the rate of profit on capital in Colombia and found a close correlation. According to the authors, in the last decade of the 20th century, the Colombian economy went through a series of neoliberal reforms. They were a failure, as the average rate of growth during this neoliberal transition was only 1% a year. Indeed, the Colombian economy registered its worst recession in 1998-2000 and the industrial share in GDP fell to 14.5%. In this period, the rate of profit reached its lowest level.

In the first decade of the 21st century, economic growth picked up to an average 2.6% a year, but this was mainly due to mineral production and construction. There was further deindustrialization as the industrial share in GDP was only 10.9% in 2019. The Colombian economy was increasingly a ‘one trick pony’ based on minerals and energy production.

Profitability recovered during the global commodity boom from 2002, reaching 19.8% in 2013 and an average of 16.4% in those years. But the end of the commodity boom in the second decade of this century saw a significant fallback in investment and economic growth – and then the pandemic arrived. This is the economic crisis in Colombia that Petro now has to deal with.

Petro’s reforms do not really threaten the economic power of Colombian business and foreign multi-nationals. And they may not even materialise. While his coalition party, the Historic Pact, may become the biggest group in the Colombian congress, the pro-business parties will maintain a majority. But if Petro wins it will be another blow to US ‘Monroe doctrine’ that Latin America is American imperialism’s ‘backyard’ to play in. Colombia, in particular, has been America’s closest ally in the region.

No comments:

Post a Comment