by Michael Roberts

In South Korea’s presidential election, held every five years, the

conservative candidate, Yoon Suk-yeol of the People Power Party gained a

narrow victory over the ‘progressive’ Lee Jae-myung of the ruling

Democratic Party. The turnout at 77.1%, high by international

standards, was pretty much in line with previous elections. The older

the voter, the more they voted for Yoon over Lee, although previous

enthusiasm among younger voters for the Democratic party had also waned

after five years of President Moon Jae-in’s presidency. This explains

the switch of parties in office in Korea.

The difference between the two candidates for the Blue House in Korea is much like the difference between a Republican and Democrat for the White House in the US. On foreign policy, Yoon championed a stronger alliance with the United States and even threatened “pre-emptive strikes” against North Korea, while Lee called for a diplomatic balance between the United States, South Korea’s security ally, and China, its biggest trading partner.

But foreign policy was not the issue for younger voters. Young Koreans are frustrated over housing prices, a lack of job opportunities and a widening income gap. Many have adopted a saying: “isaenggeul,” or “We can’t make it in this life.” “In the past, young South Koreans tended to vote progressive, but now they have become swing voters,” said Prof. Kim Hyung-joon, an election expert at Myongji University in Seoul. “To them, nothing matters as much as fairness and equal opportunity and which candidate will provide it. “We will be the first generation whose standard of living will be lower than our parents’,” said Kim Dong-min, 24, a student at Konkuk University Law School. In a survey last year, nearly 65 percent of the respondents in South Korea said they were sceptical that their children’s economic future would be better than their own.

Yoon’s economic program is classically neo-liberal. He supports ‘market-led approaches’, including job creation led by the private sector rather than government projects. He says he plans to cut ‘red tape’ for companies and to deregulate the virtual asset industry. He will lower capital gains and property ownership taxes to increase housing transactions. And he has proposed raising the tax threshold for cryptocurrency investments from the current 2.5 million won to 50 million won.

On the vexed housing issue, Yoon could not be more helpful to the rich and to property companies. He would abolish a planned new tax for people who earned 50 million won from stock investments, to be effective next year, and cut real estate holding taxes to increase housing transactions. Yoon says current property regulations must be eased and guided by “market principles.” And he vowed to create at least 2.5 million homes in the next five years, including 500,000 in the capital Seoul, presumably through private developments.

In contrast, Lee called for an expansionary fiscal policy and universal basic income of 1 million won ($800) per year to every individual. Lee initially said he would pay for his universal income plans by levying taxes on carbon emissions and impose a new, nationwide land ownership tax, under which homeowners would pay taxes on the land their homes occupy. Recently, however, he reneged on this and promised not to raise any taxes and instead proposed a temporary easing of property-related taxes for multiple home owners, saying he may reduce his universal income plans accordingly. Backing down on his original policies did not help.

But will anything really change in the Korean economy with Yoon in office? A G20 economy, Korea is supposedly an economic success story for capitalism, with economic growth averaging 5.5% since 1988, led by annual export growth of 9.3% a year. Korea’s GDP per person has risen from just US$67 in the early 1950s to $34,000 in 2019. But the slowdown in investment and productivity since the Great Recession has been visible. Labour productivity rose at an average annual rate of 5.5% in 1990-2011, but it has stagnated since then and remains only 40% of the three most productive OECD countries. Labour productivity is particularly low in the service sector—much lower than in peer economies and only half that of manufacturing and much lower in smaller companies.

Korea weathered the COVID-19 pandemic comparatively well, supported by a reasonably effective public health response. As a result, Korea’s economic contraction in 2020 was smaller than in most other advanced economies, with real GDP declining only by 1%. But the economy under Moon, as in many other G20 economies, slowed to an average of just 2.8 percent over the last five years, reaching only 2.0 percent in 2019. And the IMF reckons that Korea’s real GDP will still be some 2-3% below the pre-pandemic path in 2025.

The pandemic has left economic scarring through weakened corporate balance sheets weighing on investment and job creation; subdued employment due to the high number of labour force exits; and poor productivity growth. Korea was already lagging in high-skill sectors.

In my post on the last elections in 2017, I highlighted the scandals of corruption and links to the shady activities of Korea’s huge private corporations called chaebols. Korea’s past economic success depended on a state-directed industrialisation and export strategy; but that also meant close connections between its chaebols (Samsung etc) and government. In that post, I discussed Korea’s over dependence on heavy industry; the horrendously long hours for its workers; the poverty of its elderly; and rising inequalities of wealth and incomes.

The World Inequality Database shows that the top 10% of Koreans by income have increased their share of income and sharply raised their share of household wealth (property and financial assets). In the last five years, that story has not really altered – indeed things have got worse.

With nearly three-quarters of household wealth concentrated in real estate, no index illustrates widening inequality quite like housing prices. Young couples whose wealthy parents helped them buy apartments — a tradition in South Korea — saw their property value in Seoul nearly double under Moon. But the average household, on the other hand, must save its entire income for 18.5 years in order to afford an apartment in the city, according to estimates by KB Kookmin Bank.

South Korea’s poverty rate and its income inequality are among the worst among wealthy countries, with youths facing some of the steepest challenges. Nearly one in every five South Koreans between the ages of 15 and 29 was effectively jobless as of January, according to government data.

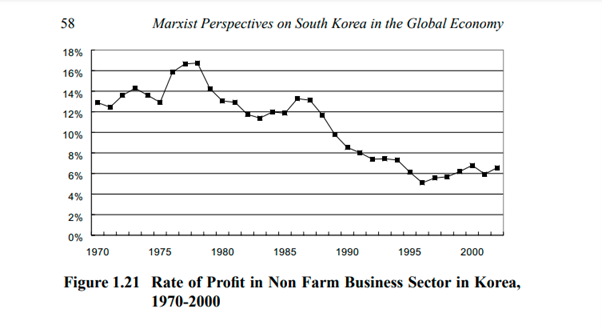

Behind the productivity and investment growth slowdown in the 21st century is the secular fall in the profitability of capital. A study by Marxist economist Seongjin Jeong of Gyeongsang National University exposed a downward trend in the profitability of the productive sectors, particularly since the mid-1980s.

We can now supplement Jeong’s study with data from the Penn World Tables going up to 2019. This shows a steady decline in profitability (the internal rate of return on capital) after a short recovery from the slump of 1997-8. The end of the dictatorship appears to have been the turning point in the profitability of Korean capital.

The future of Korean capitalism is tied up with the future of global capital. No national economy can escape that. But there are specific challenges for Korean capital too; for example, what will happen with North Korea?

If and when the regime falls there, Korean capital is in no position to integrate the people of the north into the capitalist system of the south. The cost to West German capital when the Berlin Wall fell and Germany was united again was significant and held back one of the most successful capitalist economies for a decade. The disruption to Korean capital would be very much greater, especially if this should happen in this period of economic stagnation and political turmoil as the world is experiencing now. North Korea remains the elephant in the room for the South.

No comments:

Post a Comment