by Michael Roberts

The UK economy was the hardest hit of

the top G7 economies in the year of the COVID. Real GDP fell 9.9%,

which the multi-millionaire and richest man in the British parliament,

Conservative Chancellor, Rishi Sunak admitted was the worst contraction

in national income in 300 years!

The UK government also failed to protect the people from COVID-19. Following a resurgence of infections over the winter, around 1 in 5 people in Britain have so far contracted the virus, 1 in 150 have been hospitalised, and 1 in 550 have died, the fourth highest mortality rate in the world. While output partially recovered in the second half of 2020, the latest lockdown and temporary disruption to EU-UK trade at the turn of the year will deliver yet another fall in GDP in Q1 2021.

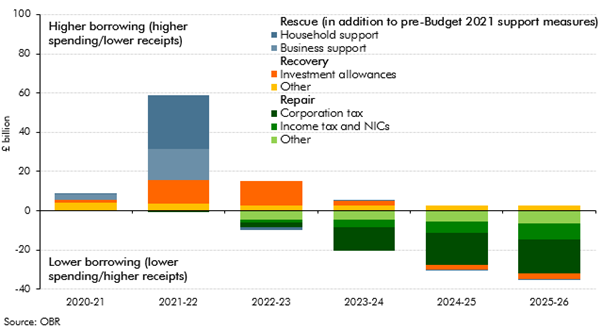

This has forced the government to extend its COVID support packages in Sunak’s government budget for 2021-22 announced today. They have all been pushed on to end-September in the hope that the fast vaccination rollout will enable the economy to open up by then and avoid a sharp rise in unemployment and small business bankruptcies by the end of this year.

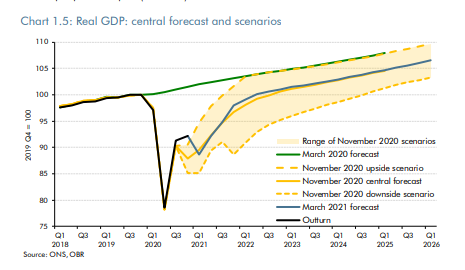

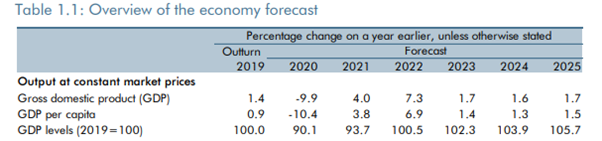

The optimistic government forecast is that the UK economy will bounce back by about 4% this year and eventually GDP will regain its pre-pandemic level in the second quarter of 2022, or some two and half years since the pandemic broke. Even if that is possible, unemployment is set to rise by another half a million to 2.5m, or 6.5%. But that assumes all the 4.7m workers currently furloughed will retain their jobs next September. Indeed, even if these growth forecasts are met, the UK economy will still be short by 3% from the pre-pandemic growth rate, which was already weak. This is clearly not a V-shaped recovery by a reverse square root.

Source: OBR

Longer term, the official forecast for average real GDP growth is just 1.7% a year, or some one-third below pre-2019 growth rates. That suggests a significant impact from ‘scarring’ to employment and investment capacity from COVID and from the loss of trade from Brexit.

Source; OBR

What are Sunak and the Conservatives proposing as a recovery plan for the UK economy? It boils down to trying to boost investment in the capitalist sector of the economy with massive tax breaks, new ‘freeports’ where large businesses can avoid tax and regulations; and through cheap guaranteed loans for businesses.

But there is no help for public services and public sector workers. A public sector wage freeze will continue – and this is after the longest squeeze in average real wages (some 18 years) since the end of Napoleonic Wars in 1822! There is no planned boost in funding for public services apart from limited increases in the health sector, where ‘stealth’ privatisation of NHS resources will be stepped up. And there is little help for hard-pressed local councils to meet their obligations, so that most are being forced to raise local taxes this year just to stop going bust. At the same time, the government did not opt to tax the huge ‘windfall’ profits made by hedge funds and financial institutions racked up from speculating in the booming stock markets of the world while millions were relying on COVID welfare. One former hedge fund manager, employer and friend of Sunak paid himself $343m in dividends from speculation in 2020!

The government announced the setting up of a National Infrastructure Investment Bank to be centred in the north of England with a piecemeal funding of #12bn. Public investment to GDP will rise to over 2.5% for the first time in decades, but in a capitalist economy, it is business investment that drives incomes, employment and productivity – and on this marker, the UK economy is operating abysmally. The forecast for business investment growth, despite the government’s talk, looks dismal.

My calculations from the official forecast suggests that business investment will rise to about 7.8% of total national spending by 2025 from the COVID slump of 7.1%. But even in 2025, that investment rate will be below 2016 levels and only 5% above 2007 – after 18 years!

Source: OBR, my calcs

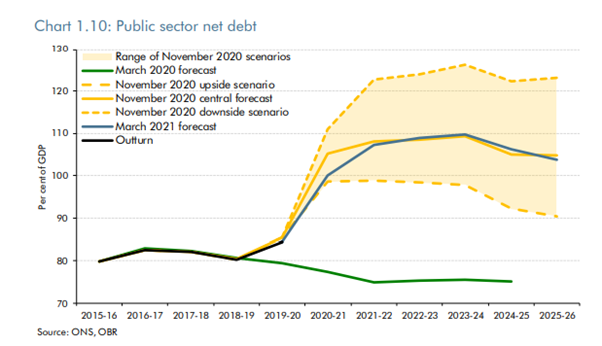

The COVID pandemic forced the government to spend unprecedented amounts for rescue support to households, businesses and public services to a total cost of £344 billion. Huge budget deficits will emerge right through this parliament and public sector debt will go over 100% of GDP and remain above that level throughout to 2025.

Sunak talked strongly about putting public finances in order. There is much debate about whether it matters or not if public sector debt is so high when interest rates on debt are so low. Indeed, the interest cost on this debt is expected to fall to a historic low of just 2.4 per cent of total revenues.

Sunak still thinks it matters and plans to raise revenues to reduce the annual budget deficits to 2025. There is a plan to hike corporation profits tax from 19% of GDP to 23% for larger firms, but it won’’t be applied until 2023 and even then the rate will be no more than the OECD average. Sunak will freeze income tax thresholds, so that people will start paying tax at lower real incomes than before. And it’s not true that the government is avoiding austerity. Apart from not reversing the huge cuts to local and public services over the last ten years, the Sunak government will cut government spending by another #4bn a year from hereon. Indeed, the total tax burden for British people will rise to its highest level since the early 1960s!

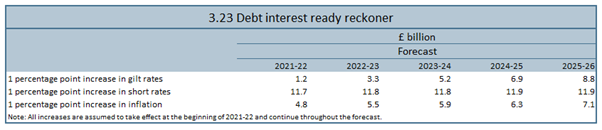

And can the public debt burden be controlled? It all depends on growth. The simple formula for containing the debt to GDP ratio is if the real GDP growth rate (g) is faster than the rise in the interest costs of the debt (r). But if real GDP growth (g) is only likely to average 1.7% a year, then it won’t take much of a rise in r to see debt to GDP rising.

According to the OBR, “the 30 basis point increase in interest rates that has happened since we closed our forecast on 5 February would already add £6.3 billion to the interest bill in 2025-26 published in this document. All else equal, that would be enough to put underlying debt back on a rising path relative to GDP in every year of the forecast.”

Supporters of Modern Monetary Theory argue that the public debt level does not matter anyway because the Bank of England can just print money to cover the debt increase. Indeed, it has done just that during the year of the COVID. So the government could order the Bank of England to continue printing money and funding asset purchases at just 0.1%, regardless of economic and financial conditions and whatever happens to inflation.

But if the size of the debt rises, it will increase the amount of debt servicing costs, if government bonds are used to increase and service the debt. That will eat into available funds for government to spend on services over time. If interest rates are held down and the Bank of England ‘’monetises’’ the debt, then foreign investors will start to take their money out of sterling and the pound will slide, driving up inflation. There is no ‘free lunch’ in debt and no country is an island, including the British Isles.

It all depends on whether the UK economy can ‘’grow out’’ of its debt burden as it did after the second world war through a combination of high public investment and rising inflation (that eventually forced the devaluation of the pound). Given that the profitability of capital in the UK is at an all-time low and the business investment rate worse than in any other major economy, the prospects of achieving that are small. Before this parliamentary term ends, the UK economy could be facing a new economic crisis.

No comments:

Post a Comment